Comets probably delivered Earth its water billions of years ago, new study reveals (Image Credit: Space.com)

Water. All life on Earth requires it in some way or another, and it’s hard to miss that roughly 70% of our planet’s surface is covered in the stuff. Thus, understanding where Earth’s water came from is a very important part of understanding life’s origins, and researchers were pretty sure they knew how it got here — up until 2014.

Basically, scientists previously believed that Earth’s liquid reservoirs arrived here on icy asteroids and comets from the outer regions of the solar system during the early stages of Earth’s formation. However, a 2014 analysis of the molecular constituents of water on the comets that likely seeded Earth’s water cast doubt on the hypothesis.. And now, the researchers think they know why their analysis of water on these icy bodies posed such a conflict.

The connection between those icy comets — which are called Jupiter-family comets because their orbits are affected by Jupiter‘s gravitational influence — and Earth’s water rests on a key molecular signature. That signature has to do with specific ratios of the hydrogen variant, or isotope, called deuterium. In general, ratios of deuterium to regular hydrogen in water give scientists a strong clue as to where that water formed. Typically, water with more deuterium is more likely to form in colder environments, which means water with higher levels of deuterium should have formed further away from the sun.

For the last few decades, deuterium levels in water found in the vapor trails of several Jupiter-family comets displayed similar levels to that of Earth’s water.

“It was really starting to look like these comets played a major role in delivering water to Earth,” Kathleen Mandt, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center said in a statement.

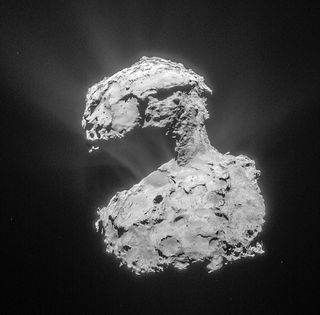

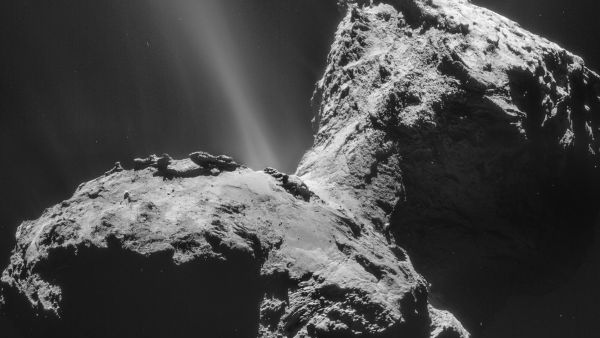

But uncertainty was raised when the European Space Agency‘s 2014 Rosetta mission to the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, or 67P for short, found higher concentrations of deuterium on any comet — about three times more deuterium than there is in Earth’s oceans, which have roughly 1 deuterium atom for every 6,420 hydrogen atoms.

“It was a big surprise and it made us rethink everything,” Mandt said.

But the story isn’t over yet. Mandt and her team decided to revisit Rosetta’s deuterium measurements of 67P, and through lab studies and comet observations, they found that cometary dust might be affecting the readings of the deuterium ratio that scientists observed in 67P’s vapor.

When comets pass closer to the sun during their orbit, their surfaces warm up, which can release gas and dust from the comet’s surface. Water with deuterium sticks to dust grains more readily than regular water does, and when ice clinging to the dust grains is released into the vapor trail of a comet, it could give observers the impression that the water in the comet is more deuterium-rich than it actually is.

“So, I was just curious if we could find evidence for that happening at 67P,” Mandt said. “And this is just one of those very rare cases where you propose a hypothesis and actually find it happening.”