Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare

Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare (Image Credit: airandspaceforces)

Advances in autonomy and uncrewed systems technologies offer a once-in-a-generation opportunity to combine the lethality of 5th-generation fighters with Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) designed to disrupt and defeat China’s counterair operations. And, unlike many advanced systems now in development, the Air Force could begin to acquire CCA at scale this decade instead of in a distant future that would be dangerously late considering China’s rapid defense buildup.

The Mitchell Institute conducted a wargame and associated studies to assess how a family of uncrewed Collaborative Combat Aircraft could increase the lethality, survivability, and capacity of the Air Force’s air superiority forces for operations in highly contested environments. Projecting decisive military power to distant theaters has long relied on the Air Force’s ability to achieve air superiority by conducting offensive and defensive counterair missions to defeat an adversary’s fighters, surface-to air missiles, battle managers, and other air defense threats.

Establishing effective air superiority is an essential, baseline requirement for any joint operation to defeat China’s aggression in the Pacific. The U.S. Air Force defines this mission as achieving “that degree of dominance in the air battle by one force that permits the conduct of its operations at a given time and place without prohibitive interference from air and missile threats.” Yet today, this hallmark of national power is at risk due to the nation’s failure to modernize Air Force air superiority forces in recent decades to keep pace with China’s unprecedented military buildup.

Neither air superiority nor victory are American birthrights … both are at significant risk.

Gen. Mark Kelly, Commander Air Combat Command

After the success of Operation Desert Storm’s air campaign, the U.S. Air Force continued to modernize its air superiority forces by developing the 5th-generation F-22 air dominance fighter along with new air-to-air weapons. Despite these efforts, force structure and program cuts severely eroded the Air Force’s ability to dominate in the air. A series of Pentagon decisions beginning in the early 1990s essentially froze USAF’s force modernization. The Department of Defense accelerated retirement of Vietnam-era capabilities like F-4s and at the time early model F-16s and also directed the Air Force to halve and then halve again its planned acquisition of the stealthy F-22, then the foundation of its future air superiority force.

The Air Force originally planned to buy 648 production F-22s, close to a one-for-one replacement of its F-15A/D inventory. The Bottom-Up Review reduced this target to 442 F-22s, and the 1997 Quadrennial Defense Review further cut it to 339 aircraft, primarily due to DOD’s desire to reduce spending and achieve a post-Cold War defense budget “peace dividend.” In 2008, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates ended the program after the Air Force acquired only 187 total tails, reasoning that F-22s were not needed for current operations and F-35s—then in development—would provide sufficient overmatch against lesser adversaries in the future. Gates argued China would not have a single stealth fighter before 2020, by which time contemporary plans projected the Air Force would have 400 F-35s and would still be acquiring some 80 more per year.

DOD also shifted its force design priorities in response to the 2001 terrorist attacks on the U.S. and subsequent counterterror/counterinsurgency operations. Instead of building new capabilities to deter peer adversaries, defense spending increases in the 2000s and much of the 2010s helped the U.S. Army sustain its security operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. DOD directed the other services to invest in capabilities like remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) to support these ongoing operations.

In contrast, China’s rapid military modernization after Desert Storm created what is now the world’s most sophisticated integrated air defense system. China tailored its warfighting strategy and its area access/area denial (A2/AD) strategy to take advantage of U.S. forces’ limitations by enabling its own forces to:

- Quickly achieve a dominant position in the battlespace before U.S. and allied military reinforcements can deploy from their homelands and other locations to engage in combat.

- Inflict unacceptable loss rates on U.S. air forces, in the air by using advanced forces such as long-range J-20 counterair fighters carrying the world’s most advanced air-to-air missiles, and on the ground by directly attacking U.S. theater air bases.

- Focus its attacks on the rarest, most valuable, and hardest-to-replace U.S. air assets. This can be seen in the PLA’s investments in a variety of weapons designed to attack U.S. aircraft carriers and airborne high-value airborne assets (HVAA) like AWACS.

- Degrade U.S. airborne battle management and command and control networks and other means to gain information dominance.

- Degrade U.S. sortie generation operations by striking their air bases and ground support capabilities. Another PLA air base attack objective is to compel opposing air forces to reposition their high-value assets from the Pacific’s First Island Chain to more distant bases, increasing the ranges they must fly to the battlespace and reducing their sortie rates.

- Take full advantage of China’s “interior lines” to ensure the PLA’s own high-value assets become high-risk targets for U.S. forces. For example, the PLAAF’s KJ-500 radar systems provide early threat warnings and target cues to long-range air defenses on the PLA Navy’s (PLAN) surface action groups. These surface action groups provide an outer layer of defenses for PLA forces in the Taiwan Strait while remaining under the umbrella of a network of long-range fighter aircraft and coastal SAMs.

A vital element of China’s military modernization campaign was its development of new air superiority capabilities like the 4th-generation J-16 and 5th-generation J-20 “Mighty Dragon” stealthy fighter, plus the advanced missiles they need to complete long-range air-to-air kill chains. The Shenyang J-16 is a derivative of Russia’s Su-30, upgraded with an AESA radar, composite materials for reduced weight, and the ability to carry indigenous Chinese PGMs. The J-20 is a long-range stealth interceptor designed to keep at bay U.S. 5th-generation fighters. According to a Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) report, “its combination of passive sensors, AESA radar, [low observable] features, range on internal fuel, and long-range missiles make the J-20 a qualitatively greater threat than any previous non-Western combat aircraft.”

Meanwhile, 33 years after the end of the Cold War, the U.S. Air Force’s air superiority force predominately consists of the same fighters, mission systems, and weapons that first joined the operational force during the 1970s and 1980s. While these systems have continued to benefit from upgrades, this force is not sized for peer conflicts, and the average age of its fighter inventory exceeds 28 years, the oldest it has ever been. This high-risk force will struggle to operate effectively in highly contested environments of the kind that will exist during a conflict with China.

Yet a key objective of the U.S. National Defense Strategy is to deter China by creating a force capable of denying the PLA the ability to achieve its campaign objectives rapidly. To achieve this deterrent effect, the U.S. Air Force must develop and acquire disruptive, asymmetric capabilities and concepts for conducting counterair operations. The United States cannot afford to match China aircraft-for-aircraft, missile-for-missile, or ship-for ship. Even if that was a desirable approach, DOD would never have the resources—money and personnel—or the time to do so.

The Air Force’s air superiority fighter inventory now consists of 179 aging 4th-generation F-15C/Ds and 185 5th-generation F-22s. Roughly 20 percent of these F-22s are training, test, or backup inventory aircraft that are not combat-coded. The service’s slowly expanding F-35 force is capable of a range of offensive and defensive counterair operations, including airborne electronic attacks and air-to-air engagements, but remains small. The Air Force had only 334 F-35As in its inventory by the end of fiscal 2022, and in calendar year 2023 received about half of the 80 F-35As it had originally planned to acquire annually—again, in large part due to inadequate budgets. These forces are supported by E-3B/G AWACS that are in their fourth decade of service. In early 2023, the Air Force awarded a contract for an AWACS replacement that is based on the E-7 “Wedgetail” aircraft acquired by Australia and the United Kingdom, but these jets will take years to join the force.

As Gen. Mark Kelly explained in mid-2023: “We literally ate the muscle tissue of the Air Force in the form of reduced fighter capacity, reduced readiness, putting hard miles on older aircraft, driving more extensive sustainment efforts.” The lack of fighter capacity due to aging aircraft and other reasons is why the Air Force was forced to withdraw F-15C/Ds from the strategically vital Kadena Air Base in Okinawa in late 2022 without direct, permanently assigned backfill aircraft. There just were not enough fighters available, so units must rotate to the base for the next several years until new jets can be stationed there.

The Air Force’s Next-Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) family of systems will be critical to maintaining its combat edge over China, but the crewed component of NGAD may not be available in significant numbers until the 2030s. But other parts of the NGAD family of systems—AI-enabled CCA—could be available sooner. That, plus maximized F-35A acquisition in the next Future Years Defense Program, would reduce risk this decade. “Extensive analysis unambiguously shows that the current fighter fleet will not succeed,” Kelly has said. The Air Force “must change now to provide the capability and capacity in the most affordable way in tightly constrained budgets to meet the peer threat.”

Wargame Insights

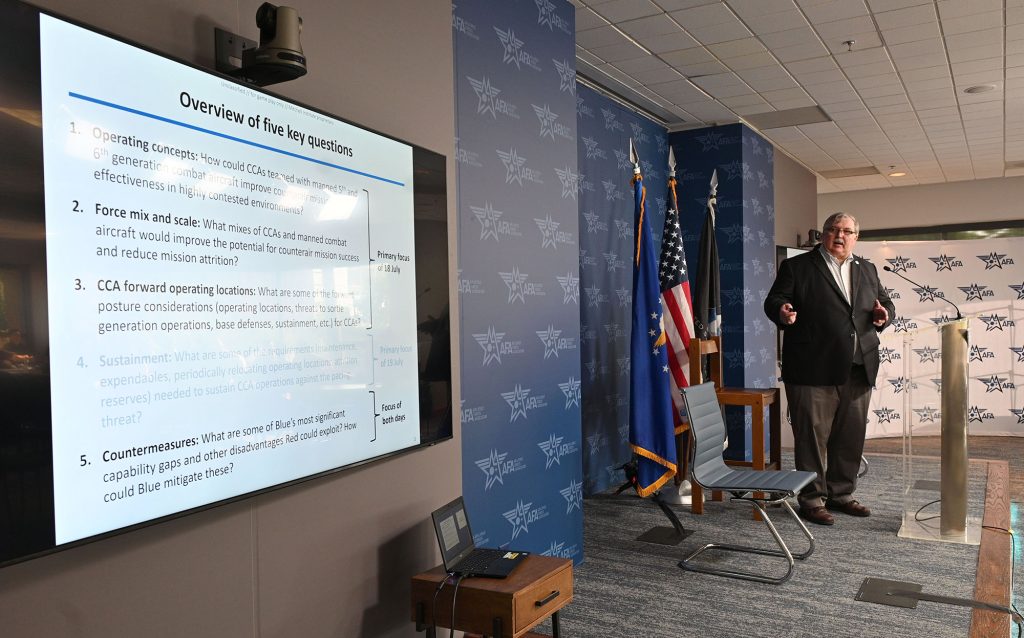

During the July 2023 wargame, the Mitchell Institute tasked top-performing operators, technologists, and engineers from the Air Force and defense industry to assess how a mix of uncrewed CCA and crewed combat aircraft could achieve the degree of air superiority required to defeat peer aggression. Organized into three “blue” U.S. campaign planning teams, these experts proposed concepts and prioritized capabilities for CCA to conduct counterair operations during the first two weeks of a U.S. campaign to blunt, and then defeat a notional 2030 PLA invasion of Taiwan.

Each team explored how the Air Force could use mixes of lower-cost and moderate-cost CCA to disrupt a peer adversary’s A2/AD operations and enable crewed and uncrewed aircraft to perform multiple counterair missions over long ranges with reduced attrition. CCA capable of operating from small, dispersed runways or even without runways could help sustain combat sortie generation rates while under attack and reduce the risk of aircraft attrition on the ground. Launching some CCA variants from mobile ramps or catapults and recovering them with parachutes and airbags may be feasible for smaller designs, where a less than 100 percent recovery rate could be acceptable. Alternatively, smaller aircraft could be designed for short takeoffs and landings using portable arresting gear, allowing them to operate independent of long runways, which are more easily located and targeted by adversaries. And because some CCA may not need to fly frequently to support pilot training, they could be postured in forward locations like other pre-positioned materiel, reducing the need to rely on long, costly supply chains that will be under attack at the start of a conflict.

The single most important insight from Mitchell’s 2023 wargame is the potential to use a family of CCA as lead forces to disrupt and then help suppress China’s advanced integrated air defense system (IADS). Experts agreed it is not feasible to match China fighter-for-fighter and missile-for-missile in the battlespace, given the Air Force’s fighter inventory and the PLA Air Force (PLAAF) will have multiple “home team” advantages, including the ability to operate from air bases adjacent to the Taiwan Strait. Instead, all three wargame teams proposed concepts of operations that initially used CCA at scale to disrupt China’s IADS and to level the playing field against the PLAAF. This mirrors the logic behind DOD’s Assault Breaker initiative from the 1980s and its 2014 to 2018 Third Offset Strategy, which sought to develop asymmetric capabilities to offset a peer adversary’s superior combat mass and proximity to the battlespace.

Importantly, all three wargame teams also chose to use a mix of CCA, including different variants designed as airborne sensors, decoys, jammers, or weapon launchers to disrupt and stimulate the PLA’s IADS, locate its critical nodes, absorb fires, and begin to attrit threats in advance of crewed aircraft. Dispersing these functions across a mix of CCA can improve operational resiliency and increase the number of airborne “nodes” adversary forces must attack. Like remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) sensor-shooters that pioneered a new way of conducting precision strikes, CCA will be more than intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) “information gatherers;” while lower-cost CCA may lack the mission systems and full functionality of 5th-generation fighters, an adversary has no reliable way of determining how CCA are equipped and must address them all as threats.

Another insight is that CCA can increase the Air Force’s capacity to generate lethal mass for counterair operations. Appropriately equipped CCA can perform as force multipliers that increase the number of sensors and weapons the Air Force can project into contested battlespaces. They can also extend the sensor and weapon ranges of stealthy crewed aircraft they team with, increasing their lethality and survivability. Designing weaponized CCA with at least enough survivability to reach their air-to-air missile launch points was a critical wargame insight. Reducing attrition of Air Force fighters and their crews would be a major force multiplier over the course of an air campaign, given DOD-mandated force cuts over the last 30 years caused the Air Force to divest its combat attrition reserves. Needed to conduct extended combat operations in highly contested environments.

CCA will multiply the Air Force’s diminished combat inventory in another way: by getting its non-stealthy combat aircraft into the fight for air superiority. For instance, notional CCA designs available to wargame experts included a long-range, air-launched design that carries two air-to-air weapons or four 250-pound class Small Diameter Bombs. The experts used 4th-generation F-15EXs and B-52 bombers to launch these weapon-carrying CCA while remaining outside the range of China’s IADS. And since these CCA could also be ground-launched by rockets without the need to use runways, experts pre-positioned them at dispersed operating locations in the Philippines and Ryukyu Islands. Creating this dispersed posture had the added benefit of improving the resiliency of the Air Force’s combat sortie generation operations.

Experts participating in Mitchell’s wargame also preferred to use a mix of lower-cost CCA they classified as expendable systems and moderate-cost recoverable CCA that could be attritted if mission needs required in the highly contested battlespace that will exist for hundreds of miles around the Taiwan Strait. Experts chose to use expendable CCA in significant numbers during the first few days of their air campaigns as decoys, jammers, active emitters, and other ways that risked their loss in highly contested environments. As their campaigns progressed, experts shifted toward using a larger number of moderate-cost CCA capable of carrying larger weapons payloads and surviving to return to their forward operating locations and regenerate for additional sorties.

Finally, wargame experts suggested there is a need to develop concepts for operating CCA with other uncrewed aerial vehicles for counterair missions, rather than solely using them as adjuncts for crewed aircraft. Of note, operating CCA in this way would require providing them with more advanced autonomy and other technologies that would add to their cost. Militaries have a long history of attempting to use emerging technologies to marginally improve the performance of their existing systems, such as at the dawn of U.S. military aviation when the U.S. Army initially believed fixed-wing aircraft could best serve as artillery spotters supporting ground operations. Constraining CCA to supporting crewed aircraft operations only limits their warfighting potential. Collaborative autonomous CCA operations will increase pressure on an adversary, an essential requirement for peer conflict in extremely large theaters such as the Pacific. This said, experts unanimously agreed that CCA are complementary and additive capabilities that will not reduce the Air Force’s 5th-generation fighter requirements. Both are needed to prevail over peer aggression.

Recommendations for the Air Force

Warfighting and technology experts from the Air Force and industry agree that fielding a family of CCA for offensive and defensive counterair operations should be accomplished as rapidly as possible. It will be a major challenge to achieve air superiority in a conflict with China today and will grow more difficult as the PLA fields its next generation of airborne and sea-based sensors, combat aircraft, and very long-range air-to-air and surface-to-air missiles. Developing CCA as part of the Air Force’s force design in this decade is a fleeting opportunity to enhance capability in the near term to deter peer aggression. Yet rapidly fielding these aircraft will require coordinated and concerted support from lawmakers, DOD leadership, and industry, given the scale of changes required to integrate them into operational units.

Additional resources are needed to develop, acquire, operate, and sustain a mix of CCA. The following recommendations are based on insights from Mitchell Institute wargames and related studies:

• The Air Force should conduct trade-off analyses to determine an optimal mix of CCA in its future force design. These analyses should seek to create an inventory of CCA types that balance their individual attributes, such as their sizes, low observability, ranges, mission systems, and unit costs, with their mission requirements. Determining the right trade-offs between these design features will inform the development of a CCA force design that maximizes the Air Force’s combat effectiveness and return on investment. These CCA will be complementary and additive capabilities that will not reduce the Air Force’s requirements for 5th-generation fighters and other advanced crewed systems.

• The Air Force should create operating concepts for using expendable and recoverable/attritable CCA as lead forces to disrupt China’s air and missile defenses and other A2/AD operations. These operating concepts should address how CCA could perform as lead forces to complicate the PLA’s counterair targeting, identify its high-value air defense nodes, and cause PLA defenses to deplete their air-to-air and surface-to-air weapons on lower-cost uncrewed systems. This is not the same as using CCA to increase the Air Force’s capacity to fight attrition-based warfare. Instead of relying on CCA to simply generate more mass, uncrewed systems combined with new, disruptive, cost-imposing operating concepts can create an asymmetric combination the PLA will find difficult to counter.

• The Air Force should acquire CCA at scale to increase its capacity to project affordable counterair mass into highly contested areas. CCA can be force multipliers by collaborating with 5th-generation aircraft and other uncrewed systems, while also operating independently to increase the weapons and sensors the Air Force can project over long ranges into highly contested environments. CCA designs capable of performing as penetrating “weapon trucks” would help offset the PLA’s growing counterair forces, improve the survivability of the Air Force’s 5th-generation fighters, and multiply the number of weapons crewed fighters can bring to the fight. These CCA should have the survivability and range to ensure they will reach their weapon launch points. The Air Force’s future force mix should also include CCA with long ranges that can be launched from non-stealthy bombers and fighters to disrupt the PLA’s air defense operations and help pave the way for more capable counterair aircraft.

• The Air Force should field CCA that will reduce its dependence on large, fixed air bases in the Indo-Pacific and other theaters. Reducing the Air Force’s current reliance on main operating bases with long runways in the Pacific theater would improve its ability to generate combat sorties while under attack as envisioned by its Agile Combat Employment concept. CCA that can operate from short runways or launch without using runways would help create a more dispersed, resilient forward posture. A network of dispersed CCA operating locations would also complicate the PLA’s ability to find, fix, and attack the Air Force’s counterair forces when they are most vulnerable: on the ground and preparing for combat sorties.

• The Air Force should increase the lethality of its CCA over time by developing new munitions or adapting current weapons to take maximum advantage of their payload capacity. As the Air Force iterates its future CCA designs, it should take advantage of technologies like smaller engines, compact rocket motors, and miniaturized components to design smaller weapons that would increase the number of targets CCA can attack per sortie. This will be critical to the success of operations to rapidly halt a Chinese offensive.

• DOD should work with Congress to increase Air Force funding to create a force design that combines uncrewed CCA and 5th-generation and 6th-generation combat aircraft for decisive counterair operations. Decades of insufficient budgets have created a high-risk Air Force that lacks the force capacity, modernized capabilities, and readiness required for a major peer conflict. Reversing this decline requires growing the service’s annual budgets by 3 to 5 percent for a decade or more to acquire CCA, increase F-35A acquisition, acquire other new counterair weapons systems, and improve air base defenses for peer conflicts.

• Analyses are also needed to determine capabilities and operating concepts to support and sustain a high tempo of CCA operations in forward theaters. These analyses should address requirements to pre-position CCA and their logistics in the Indo-Pacific, appropriate dispersal locations for CCA launch and recovery operations, and materiel and personnel requirements to sustain CCA combat operations at scale during a peer conflict. Determining CCA theater logistics requirements will be a critical step toward determining the attributes of future CCA designs.

The Mitchell Institute’s wargames and related research strongly support the Air Force’s proposition that CCA will help mitigate the Air Force’s existing—and growing—capability and capacity gaps that threaten its ability to achieve air superiority. CCA combined with crewed 5th- and future 6th-generation fighters have the potential to disrupt China’s A2/AD operations and then deny and impose costs as called for by the National Defense Strategy. The stakes for creating this new, hybrid force design have never been higher, given China’s unchecked campaign to field new A2/AD weapon systems and proliferate them to other actors that threaten the security of the United States and its allies and friends.

Col. Mark Gunzinger, USAF (Ret.) is a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense and the director of Future Concepts and Capability Assessments at The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.