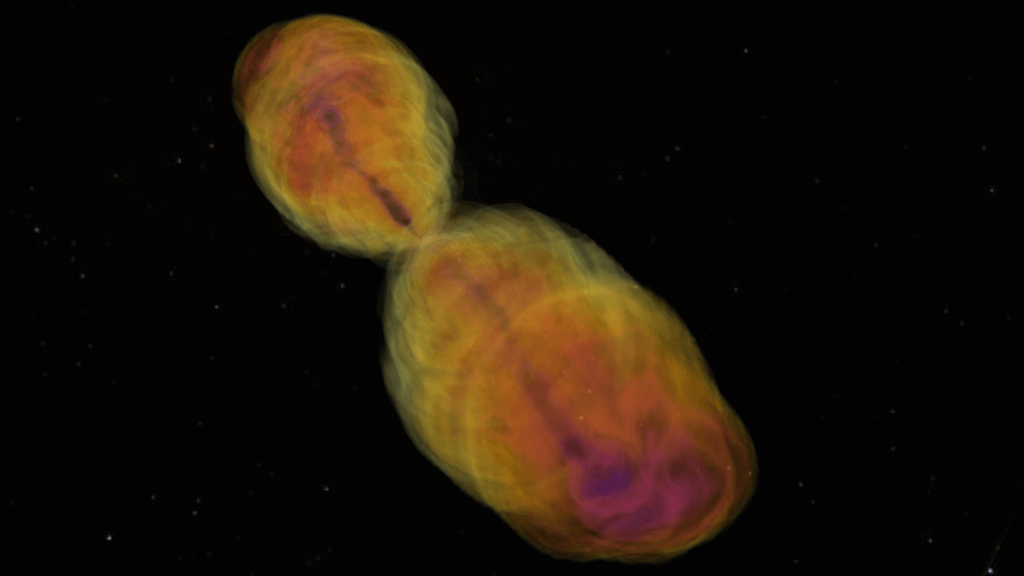

Cocooned, dying stars may cause sudden, bright blasts that confound scientists (Image Credit: Space.com)

Extremely fast cosmic explosions puzzling scientists may be outbursts arising from dying stars, new research suggests.

Dubbed fast blue optical transients (FBOTs), because of their “blue” heat and very rapid evolution, only a handful of these outbursts have been recorded. (Astronomers often give them evocative nicknames, like “the Camel” or “the Koala.”)

A new model suggests the bursts happen amid the chaotic environment of a huge, dying star. Such stars shoot out powerful jets, which smash into layers of gas sloughing off the star as its fusion slows down. The model suggests that as the cocoon cools, it releases heat rapidly, which we see as the FBOT.

“When we calculated how much energy the cocoon has, it turned out to be as powerful as an FBOT,” Ore Gottlieb, a theoretical high energy astrophysicist at Northwestern University who led the research, said in a statement.

Related: Supernova photos: Great images of star explosions

FBOTs are most visible in optical wavelengths and change within a matter of days. They get bright rapidly, then fade away, much faster than a supernova star explosion typically does. They also are new to science, having been observed for the first time only four years ago.

Scientists have offered other origin stories to explain these weird bursts. Some astronomers have said FBOTs may be related to gamma-ray bursts, another set of powerful explosions associated with dying stars. These explosions, known as GRBs, occur when huge stars collapse into black holes, generating gamma rays.

Gottlieb said he isn’t sure. While GRBs and FBOTs both move at nearly the speed of light and have asymmetrical shapes, there’s a key difference between the two displays. “Stars that produce GRBs lack hydrogen,” he explained. “In FBOTs, we see hydrogen everywhere. So it could not be the same phenomenon.”

The model Gottlieb and his collaborators created accounts for this discrepancy between these two flavors of outbursts (the GRB and the FBOT). Since the hydrogen-rich stars that trigger FBOTs have the gas in the outermost layer of the cocoon, the jet cannot penetrate that far as the layer is too thick, the scientists argue.

“That’s why it fails to produce a GRB,” Gottlieb said. In these situations, the cocoon instead emits FBOT emissions, which occurs when the jet sends all its energy to the cocoon of gas, which in turn glows.

FBOTs are also visible in radio and X-ray waves, which also appear to have an explanation in the model. As the cocoon jostles against dense gas nearby the star, the movement creates radio emissions as the stellar material heats up.

The X-rays come later in the process, as a black hole is created from the collapsed star; the X-rays from the black hole are believed to leak out from the cocoon’s thin and weaker edges as it expands.

The researchers added that more observational data would help confirm the model and to create more advanced simulations of FBOT and GRB behavior. A study based on the current research was published April 11 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.