Clues to spotting life on Mars are right here on Earth (Image Credit: Space.com)

As NASA’s Perseverance rover inches along on Mars while searching for hints of ancient life, scientists on Earth are honing their skills of identifying such signs in the first place — by studying fossils of some of the oldest lifeforms on our planet.

Roughly 3.5 billion years ago, a blue-green algae known as cyanobacteria triumphed as the dominant form of life on Earth. It was also the first living organism large enough to be seen with the unaided human eye. One of the few places where this organism’s fossils (called stromatolites) can be found is in the Pilbara, a dry swath of Western Australia that’s considered to be the oldest place on Earth.

Because active geological processes on our planet routinely recycle its surface, Pilbara’s stromatolites are among the few remaining ancient rocks with preserved remnants of early terrestrial life.

Related: NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover hunts tantalizing bedrock that could hide evidence of life

It’s these stromatolites that scientists think will shed light on what signs of life to look for on Martian rocks, which are also thought to be about 3.8 billion years old.

“The more we learn about our planet’s evolution, the more we can apply that knowledge to our characterization of the Red Planet,” Eric Ianson, director of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, said in a statement.

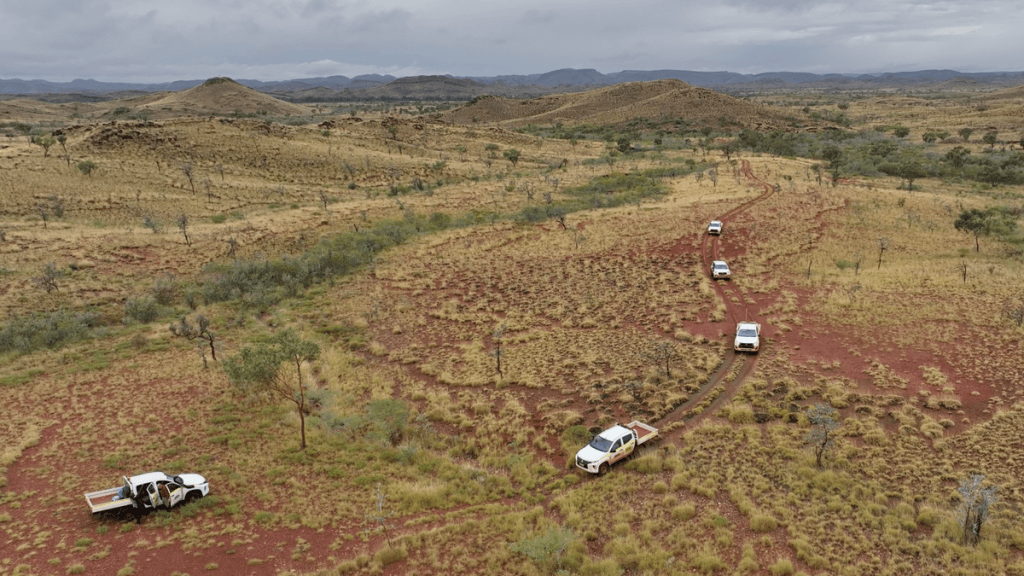

His team, along with counterparts from the Australian Space Agency, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, spent a week in the Pilbara region to do just this.

The group discussed the importance of geological locations when choosing spots to sample rocks as well as inevitable challenges that in spotting evidence of life in even Earth’s fossils entail.

“To be able to prove that a feature is biogenic, not only do you need to be able to prove that life can create it, but you also need to be able to prove that the particular version of the feature was not created by something else,” Lindsay Hays, NASA’s deputy lead scientist for Mars Sample Return and Program Scientist for Astrobiology, said in the statement. “You have to understand what else is going on in the historical record of the rock section to be able to understand what you’re looking at.”

Scientists believe knowledge gained from field trips like these will come in handy when bits of ancient Martian rocks are brought back to Earth, though that’s not likely to happen for at least a decade.

NASA’s Perseverance rover, which is exploring a Martian crater where a lake and a river delta may have flowed billions of years ago, has been collecting intriguing rock samples that are about 3.5 billion years old. Scientists plan to ultimately bring those samples home through the ambitious Mars Sample Return mission. The NASA-ESA campaign plans to send an orbiter and a rocket-equipped lander to pick up those samples to fly them to Earth, where scientists can study them for hints of past life.

As per the mission plan, Perseverance will lug the collected samples to the lander, which will be blasted into orbit by the rocket, grabbed by the orbiter and then returned to Earth. Because there is no guarantee that Perseverance will still be functioning till late 2020s, however, the rover recently dropped ten filled sample tubes in the crater as backups.

While an exciting endeavor, the mission recently ran into technical challenges spurring launch delays and cost overruns, with internal cost projections doubling the mission’s initial budget of $4 billion to between $8 billion and $9 billion.

The Senate Appropriations Committee, which shared their recommendations on NASA’s spending bill for fiscal year 2024 in a report last month, has given the space agency six months to provide a yearly budget breakdown for the Mars Sample Return mission while keeping the costs within $5.3 billion.