Astronauts celebrate success of 1st surgery robot on ISS: ‘It’s a real game-changer’ (Image Credit: Space.com)

One slice through rubber bands may pave a new pathway for space surgeons.

A robot on the International Space Station (ISS), remote-controlled by a big team on Earth, simulated surgical cuts on Feb. 10 in a historic first for space medicine. Astronauts say this work will help them fly further from Earth than ever before.

A procedure like dealing with appendicitis, noted NASA astronaut Jasmin Moghbeli during a Wednesday (Feb. 21) call with reporters, “can be a big deal if you’re far away from home and don’t have a surgeon on board.”

While crews do fly with doctors on board, not every physician is specialized in every system of the human body, she said in the space-to-ground chat. “Those (robotic) surgeries,” added Moghbeli, “will enable us to go on these longer-duration missions, further from Earth. So it’s a real game-changer.”

Related: A robot surgeon is headed to the ISS to dissect simulated astronaut tissue

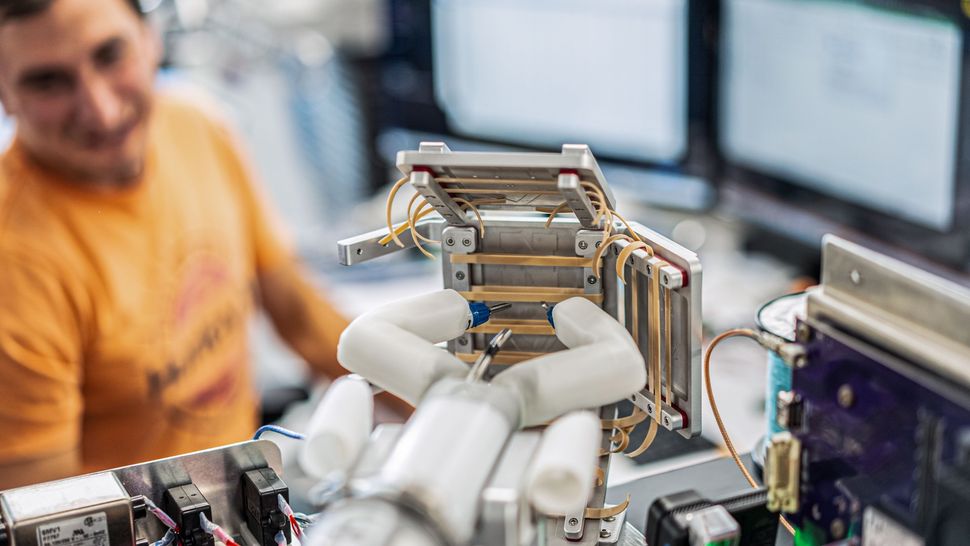

The mighty robot doing the simulated surgery is known as spaceMIRA, or “Miniaturized in vivo Robotic Assistant.” The two-pound (0.9-kilogram) device flew to the ISS aboard Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus spacecraft earlier this year.

The two-armed robot comes courtesy of Virtual Incision, a startup founded by faculty members from the University of Nebraska Medical Center and University of Nebraska-Lincoln. And it’s part of a huge set of medical research NASA wants to push forward as the agency aims to land humans on the moon as soon as 2026 with Artemis 3, on the eventual path to exploring Mars as well.

The NASA-led Artemis program aims to establish a base of operations at the moon’s south pole, but like any remote environment astronauts will not be able to fly home quickly if a medical emergency arises. SpaceMIRA shows it may be possible to get around the small time delays in orbit; perhaps that capability could be extended to the two-second communications gap moon as well, NASA administrator Bill Nelson said during the call with the ISS.

“This really sounds like a fantastic breakthrough, that even though you’ve got about a half a second delay, a surgeon on Earth can actually perform surgery on the ISS,” said Nelson, a visiting space shuttle payload specialist astronaut who flew on STS-61C in January 1986, while he was a U.S. politician focused on space matters.

SpaceMIRA made it to the ISS in large part due to a $100,000 award to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln through the U.S. Department of Energy’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR). Doctoral student Rachael Wagner helmed the grant effort, and was the first woman to operate spaceMIRA in orbit on Feb. 10.

The space robot follows years of testing on an Earth version, simply known as MIRA, that aims to provide surgical capabilities in a small device. The space version allows for “pre-programmed as well as long-distance remote surgery operation modes,” university officials stated recently.

Related: International Space Station will host a surgical robot in 2024

The simulated space surgery saw spaceMIRA wielding scissors to cut through rubber bands on the ISS. Several different surgeons took the controls from Virtual Incision’s headquarters in Lincoln, Nebraska. Reaching the ISS took some interstate wrangling; communications to ISS were ferried through NASA’s payload operations center at the agency’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

The surgical team experienced gaps of anywhere from two-thirds to three-quarters of a second in operating the controls, but they overcame that with experience. First up was Michael Jobst, a Lincoln-based colorectal surgeon. His 15 procedures with MIRA on Earth included a 2021 clinical study in which part of a patient’s colon was removed at Bryan Medical Center in Lincoln.

“You have to wait a little bit for the movement to happen; it’s definitely slower movements than you’re used to in the operating room,” Jobst said of the space procedure in the university statement.

Jobst and other participants used a screen that showed what the robot was “seeing” inside of its sealed work station on the ISS, on a rack in the U.S. Destiny laboratory, where NASA astronaut Loral O’Hara placed the experiment earlier in February. Ten rubber bands were visible on screen, stretched taut across metal panels.

The orientation session for spaceMIRA included a warning to surgeons to avoid the sides of their locker, lest they damage their robotic helper. They also were asked to minimize debris to lessen the risk to astronauts, university officials stated.

Dmitry Oleynikov, Virtual Incision’s chief surgeon, was among the people trying out the space procedure. When an observer joked it looked as though Oleynikov had done it before, Oleynikov quipped: “I’ve not done this in space!”

The robot surgery is just one of dozens of human science experiments on board the ISS. Andreas Mogensen, the Expedition 70 commander with the European Space Agency, highlighted recent 3D-printing of simulated human tissue on RedWire Corp.’s BioFabrication Facility as another promising avenue for the far future.

“Perhaps we could print organs, rather than relying on organ donors,” Mogensen mused during the phone call with Nelson and reporters. “A lot of people on Earth require organ donation, and unfortunately, we’re limited on the supply.”

Applications from space may also help with aging populations, including the MABL-A (Microgravity Associated Bone Loss-A) experiment that examined how microgravity affects bone marrow and stem cells, NASA’s Moghbeli said. Moghbeli herself worked on the MABL-A experiment last week on ISS.

“If we can understand the mechanisms that can be used to prevent and potentially even treat bone loss … that applies directly to bone loss for aging,” Moghbeli added. Preventing bone loss is also why astronauts exercise two hours daily in orbit and take experiments on how their body changes, in research that may help bedbound or senior Earth populations.