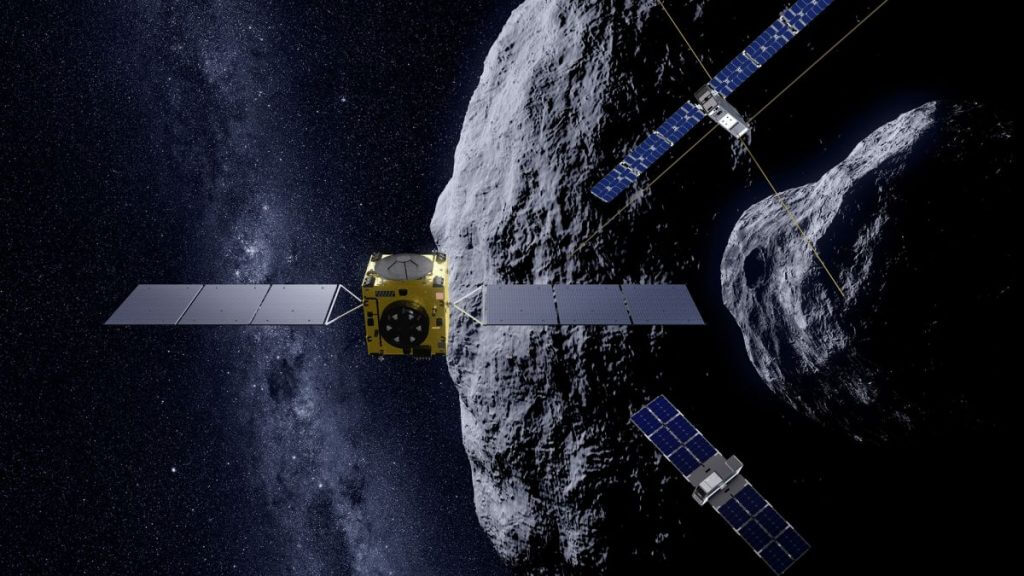

Asteroid-smash aftermath: Why Europe is sending a probe to DART-battered Dimorphos (Image Credit: Space.com)

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Hera mission will arrive at the binary asteroid system Didymos more than four years after NASA’s DART probe slammed into one of its two space rocks.

By that time, all the dust generated by the experimental collision will have settled, allowing Hera and its two companion cubesats to turn the Didymos duo into the best explored space rocks in the universe.

Hera, or its predecessor concept AIM (for Asteroid Impact Mission), was originally planned to reach Didymos ahead of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), which slammed into the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos on Sept. 26. Fitted with a suite of elaborate cameras and sensors, Hera was meant to be the witness of the milestone experiment, which was designed to validate the “kinetic impact” technique that one day might save Earth from a devastating asteroid strike. But delays in ESA’s approval process and a late funding decision disqualified the $280 million Hera from that role, its shoes hastily filled by the tiny Italy-built LICIACube cubesat.

But scientists say there is a lot Hera can offer, even in late 2026 when it is expected to reach Didymos following a launch in 2024. In fact, they argue, without Hera’s measurements, the study would be incomplete, with many unknowns left. And these questions need to be answered for the kinetic impact technique to be fully validated in case it is ever needed to ward off an asteroid strike on Earth.

Related: Asteroid apocalypse: How big must a space rock be to end human civilization?

“Hera will measure the mass of Dimorphos, which will give us a more accurate estimate of how efficient this technique was in deflecting the asteroid,” Michael Kueppers, Hera project scientist at ESA, said in a news conference on Sept. 15. “It will also characterize the physical properties of the two asteroids. Things like strength and porosity, which will help us extrapolate the data from DART to other asteroids in case that we will in the future need this technique to avoid a catastrophe on Earth.”

Hundreds of ground-based telescopes are currently observing the Didymos system, with the goal of determining how much the DART impact altered the orbit of the 534-foot-wide (160 meters) Dimorphos around the 0.5-mile-wide (780 m) Didymos. The two most powerful space telescopes, NASA’s James Webb and Hubble, too, are contributing to the observations.

The tiny LICIACube already provided images of the impact and its immediate aftermath, but those were taken from hundreds of miles away. LICIACube’s official science mission ended after it performed a close flyby of Dimorphos in the first minutes after the DART impact. The cubesat may be able to do more in the coming weeks, but with its two relatively basic cameras, there were always meant to be limitations.

“[Dimorphos] is a very low-gravity environment because it’s very small,” Patrick Michel, Hera principal investigator at Cote d’Azur University in France, said in the ESA news conference. “Because the gravity is so small, the crater can take hours to form, so we need another spacecraft detective that comes on the site and gives us the final outcome details.”

To gather these details, Hera will carry a lidar (“light detection and ranging”) sensor to map the surface of the two asteroids with great precision, a thermal camera for analyzing the chemical properties of the surface and an optical camera to enable scientists to view the final impact crater and the untouched Didymos. On top of that, two cubesats, named Juventas and Milani, will accompany Hera on its mission, equipped with additional high-tech instruments.

Juventas will carry a special low-frequency radar instrument that will be able to peek inside the two asteroids and perform a detailed X-ray scan, according to ESA. Milani will analyze asteroid dust and make observations of the surface in near-infrared wavelengths.

“It will be the first time that we will probe the internal properties and subsurface of an asteroid and chart [the characteristics] that influence the outcome of the impact,” Michel said. “We also hope to touch down on the surface of the asteroid with at least one of the two cubesats, and that will allow us to learn a lot.”

With images taken just before the impact by DART’s own DRACO camera, LICIACube’s observations of the crash and its immediate aftermath, and Hera’s detailed investigation of the longer-term outcomes, scientists will have the three necessary parameters to fully understand the effects of the experiment, Michel added.

Hera, officially approved in 2019, is currently being put together in facilities in Italy and Germany, ESA’s Hera project manager Ian Carnelli said in the news conference. By the end of next year, the spacecraft should be complete and ready to commence an extensive campaign of tests ahead of its planned launch in October 2024.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.