A simple streetlight hack could protect astronomy from urban light pollution (Image Credit: Space.com)

Light pollution is a growing threat to astronomy, but a new streetlamp technology could restore clear views of the night sky.

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) consume only about 10% of the electricity required by traditional incandescent lights and last up to 25 times longer, so it’s no surprise that they have become commonplace over the past two decades.

But there is a downside to LEDs: They’re much brighter than old-fashioned energy-guzzling light bulbs. When an entire city gets fitted with energy-saving LED lamps, this bright light scatters through Earth’s atmosphere and makes the sky glow with greater intensity.

As a result, many astronomical observatories, that in the past have been built in dark, remote locations, now see far fewer stars than they used to. In fact, the light pollution problem is worsening so fast that it offsets some of the improvements gained through advancements in telescope technology.

Related: Light pollution damaging views of space for majority of large observatories, survey finds

A study published earlier this year found that stars are disappearing from the sky at an average rate of 10% per year. This trend affects even the world’s most remote observatories. Germany-based startup StealthTransit recently tested a solution to this growing issue.

“Unfortunately, this problem haunts almost all observatories today,” Vlad Pashkovsky, StealthTransit’s founder and CEO, told Space.com in an email. “Modern telescopes are highly sensitive and feel the impact of outdoor lighting of cities located at the distance of 50 or even 200 kilometers [30 to 120 miles]. This means that virtually every observatory on Earth either already needs, or will need in the future 10 years, protection from the light of large cities.”

StealthTransit’s solution relies on three components: A simple device that makes LED lights flicker at a very high frequency that is imperceptible to the human eye, a GPS receiver, and a specially designed shutter on the telescope’s camera that can blink in sync with the LED lights. The GPS technology guides the telescope’s shutter to open only during the fleeting moments when the LED lights are switched off.

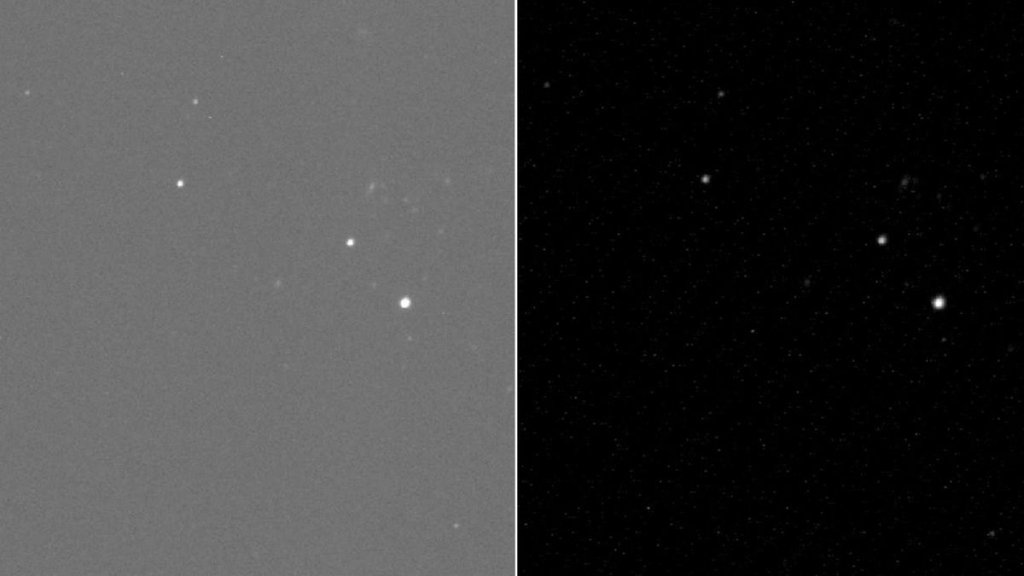

The experiments, conducted at an observatory in the Caucasus Mountains in Russia, showed that the technology, dubbed the DarkSkyProtector, could reduce unwanted sky glow in astronomical images by 94%.

“We can say that the telescope was seeing almost a dark sky at this time,” Pashkovsky said. “The important thing about our technology is that it makes all kinds of lights astronomy-friendly, including outdoor advertising and indoor lighting in apartments, offices and stores.”

The technology could filter out lights from nearby towns and villages as well as those surrounding the observatory itself.

It might sound impractical to refit an entire town with devices that allow lamps to blink, but Pashkovsky said that most existing LED lights can operate in the blinking mode and that new lamps designed specifically with sky protection in mind would be no costlier than existing LED technology. The most expensive element of the DarkSkyProtector system is the telescope shutter, which needs to be lightweight and agile enough to blink about 150 times per second.

StealthTransit tested the prototype shutter on a 24-inch-wide (60 centimeters) telescope and hopes to make the technology available for larger telescopes.

Although StealthTransit’s technology is not yet ready for commercial use, Pashkovsky said, the firm hopes to have a product fit for the world’s best telescopes in five to seven years.