‘A lot has changed’: NOAA is rewriting the book on how to rank solar storms (Image Credit: Space.com)

A lot has changed in the last 25 years in regard to space weather.

Technology has improved, and scientists have gained knowledge about extreme space weather events following historic geomagnetic storms like the Halloween solar storm in October of 2003 and the Gannon event in May 2024. Looking to the future, scientists at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) are now looking for ways to better communicate to the public about space weather events that could impact Earth. That’s why NOAA is asking for public input on how to rewrite its space weather scales.

NOAA published a request in collaboration with the National Weather Service (NWS) asking organizations and the public to share information on what revisions could help update the Space Weather Scales. The goal is to make it easier to understand space weather conditions that could develop and how they could impact humans in space and on Earth as well as different systems that have been affected in the past.

“The user base and needs have changed, the capabilities, the science and our understanding of the science — a lot has changed. And the scales for all practical purposes have not changed, and they need to.” Bill Murtagh, program coordinator for the NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC), told Space.com in an interview.

NOAA’s Space Weather Scales were created in 1999 when space weather began to gain popularity with the introduction of new technology to study weather in outer space. Spacecraft were equipped with different instruments to study the solar wind and also keep a watchful eye on the sun’s activity.

“Space weather was really starting to evolve as a science of interest across many sectors because we were starting to appreciate it as each new technology was introduced, developed, and evolved vulnerabilities to space weather came with it,” Murtagh said.

NOAA’s space weather scales were modeled after existing scales used to categorize meteorological events here on Earth. “We had the discussions here at SWPC in 1997-1998 that we should have scales, but we wanted the scales to be something the citizens of this nation could understand,” Murtagh explained.

“Everybody understands what a Category 5 hurricane is or an EF-4 tornado, so we modeled our scales after those scales, essentially, which is one through five. That’s what the citizens could appreciate, with one being minor and five being in the extreme condition.”

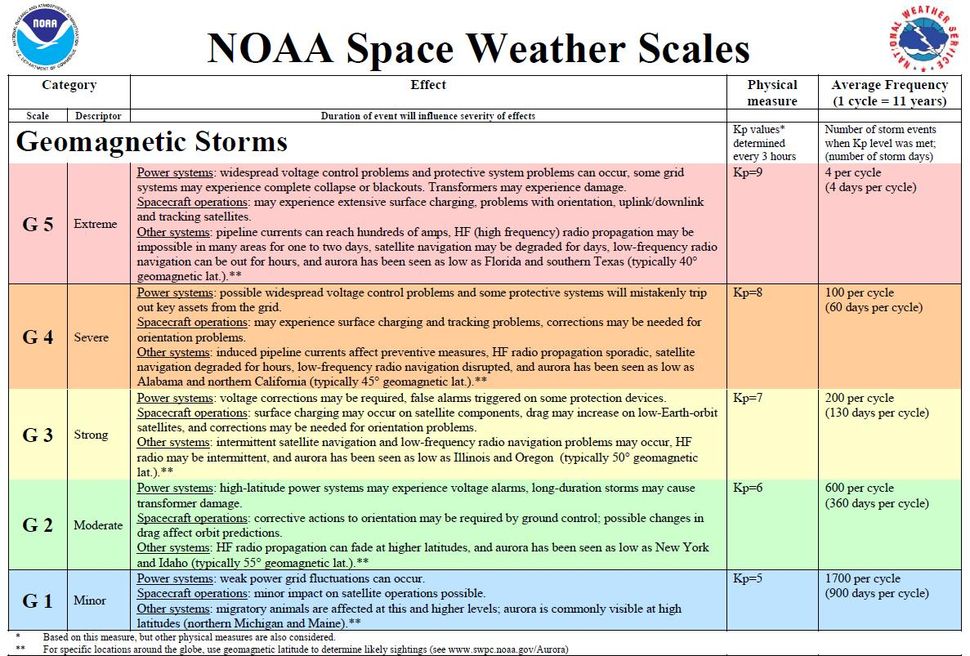

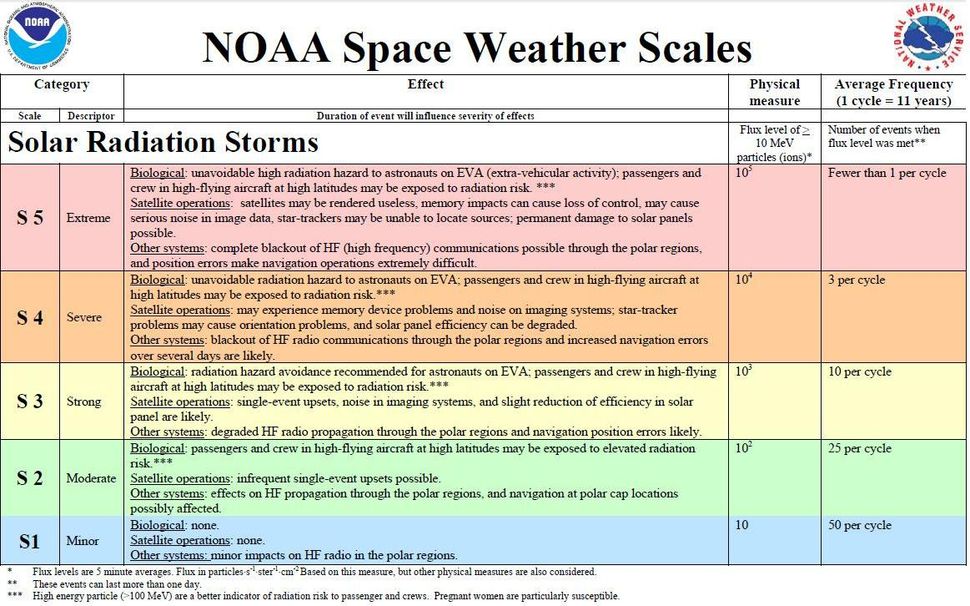

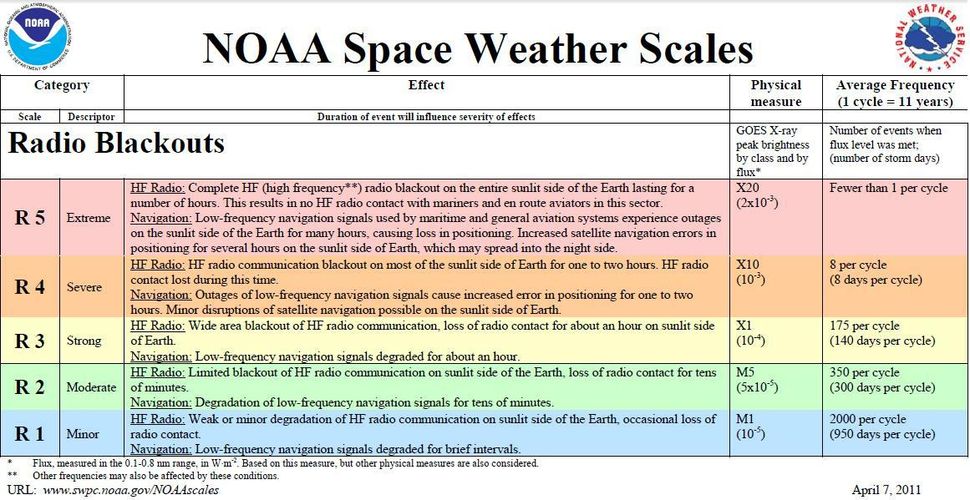

There are three different events that the scales pertain to explaining the different types of environmental impacts they can have and their severity. In addition, each of the scales includes details on how likely each type of event occurs on average and the type of intensity associated with each level.

For geomagnetic storms, the scale categories focus on impacts to spacecraft operations, power grids and other terrestrial infrastructure.

In the solar radiation categories, effects include biological impacts to astronauts and passengers on aircraft as well as how satellites and other systems could be affected.

The third scale, radio blackouts, focuses on the effects space weather could have on high frequency (HF) radio as well as navigation systems.

Murtagh explained that the scales were based on the three main groups of impacts stemming from solar flare events.

“We identified what we consider the three primary areas, the three key elements from an eruption on the sun. The first is the solar flare, the emissions, what we call the solar flare radio blackout (R). Soon after that, we’ve got our energetic particles flowing in, the energetic protons, and that’s our S-scaled radiation storm. And then the last piece, the big coronal mass ejection (CME),” Murtagh said.

“It makes its way to Earth, impacts the magnetic field, and then we have a geomagnetic storm, and that would be the G scale.”

Since the scales were created, their user base began to evolve expanding from a knowledge-hungry general public to different companies that became more engaged with how space weather can specifically impact the communities and clients they served.

For example, emergency response organizations like the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) began to inquire more from the SWPC about if and how radio blackouts could affect communications through satellite and cell phones based on the wording in the Radio Blackouts scale. Other examples included concerns with the different levels of “radiation” from a solar storm could mean.

“We’ve got the scale called Solar Radiation, and the S4 level called severe radiation. I’ve got the public being told that the radiation environment is going to increase when they’re up in the air to such degree that we’re going to call it a severe radiation storm; it causes a lot of concern,” Murtagh said.

Even airlines told NOAA that they want to better understand what the scales mean for their passengers.

“We had the major airlines here with us last year, and they all said, ‘you guys need to change that, right?’ We got severe turbulence, we got severe icing, and we know what that means, but severe radiation? Are people going to get off the plane vomiting because of radiation sickness, are they going to die? People just don’t know and so that’s another issue that we’ve had to address is the service,” Murtagh said.

Spacecraft operators are also interested in new space weather scales as more and more commercial companies depend on satellites for services, said Kim Klockow McClain, senior social scientist for the National Weather Service (NWS)

“Think of all the cubesat constellations; those things are being used as critical infrastructure in some places and are going to be what provides internet in some developing nations. We’re putting a lot in low Earth orbit in places that are so vulnerable to some of these phenomena, some of which aren’t really directly accounted for in the scales like neutral density,” Klockow told Space.com in an interview.

“We need to think about what decisions people make on the ground and go beyond just categorizing our hazards to really trying to communicate something about impacts. This is a challenge that crosses all of the hazard domains,” Klockow added.

NOAA is expected to finalize findings concerning the new space weather sacles by the end of the year, and the information will then be shared across different government agencies including the White House, the Department of Energy, the Department of Transportation, and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The results will guide the teams at NOAA and the NWS in making decisions at what revisions need to be made in the immediate and long-term.

“We’re going to say, option one is this, I think this is something we should do and perhaps with this modification, we can get it done in six months. Option two, very good idea, it’s going to take three years and I recommend we pursue it. All those kinds of discussions are going to take place and I think we could make changes to the scales that are meaningful within a matter of months into 2025,” Murtagh said.

“I think we can make some small but significant changes on the scales. We can do a lot in the short term, but there’ll be some obviously bigger efforts on the way in the coming year or so too.”