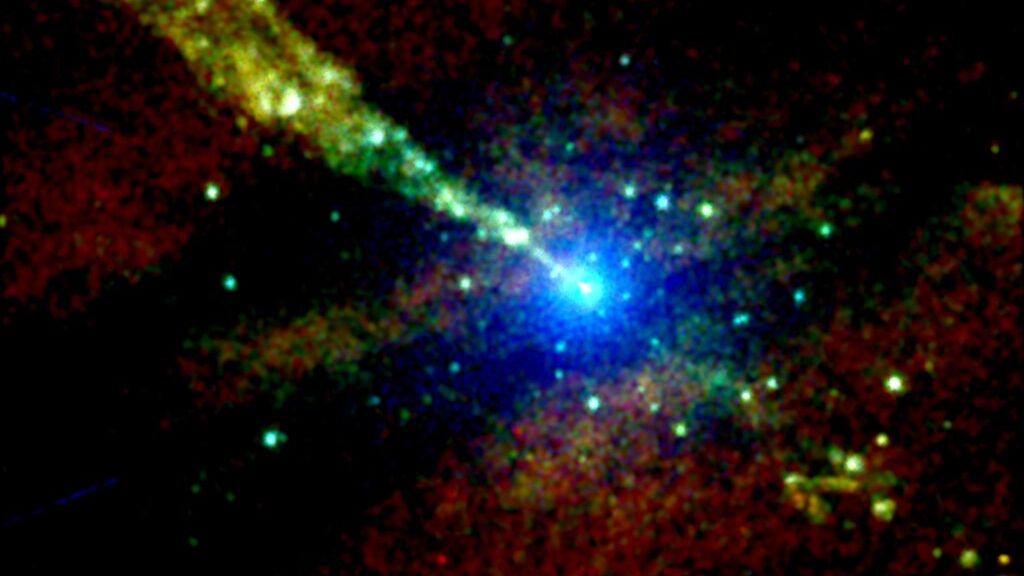

NASA’s Chandra X-ray telescope sees ‘knots’ blasting from nearby black hole jets (Image Credit: Space.com)

Astronomers have scoured decades-old data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, finding bright, lumpy features dotting a jet of energy spit out by a nearby black hole. Puzzlingly, the “knots” clock a faster speed when seen in X-rays than they do in radio wavelengths. scientists said.

“The X-ray data traces a unique picture that you can’t see in any other wavelength,” study lead author David Bogensberger, an astrophysicist at the University of Michigan, who led the new study, said in a recent news release. “We’ve shown a new approach to studying jets and I think there’s a lot of interesting work to be done.”

The study, which was published Oct. 18 in The Astrophysical Journal, comes as NASA delays its final decision about budget cuts that would determine the fate of the observatory (which faces premature cancellation after its budget was slashed due to the agency’s financial restrictions) and of the X-ray community that relies on it for research. NASA continues to operate on 2024 levels despite a new fiscal year having kicked in Oct. 1, partly due to its 2025 budget being dependent on the outcome of the presidential election and changes in party in the House and Senate, SpaceNews reported.

Meanwhile, astronomers continue to stress the science value being delivered by the X-ray telescope, which turned 25 years old in July.

In the new study, Bogensberger and his team analyzed two decades of Chandra’s observations of the active supermassive black hole lurking at the heart of Centaurus A galaxy, a somewhat misshapen elliptical swirl of gas and dust roughly 12 million light-years from Earth. At least one of the newfound “jet knots” appears to be traveling at 94% the speed of light, which was higher than the 80% of light’s speed clocked in radio observations, according to the paper.

Related: Astronomers spot unusually synchronized star formation’ in ancient galaxy for 1st time

“What this means is that radio and X-ray jet knots move differently,” Bogensberger said in the statement. “There’s a lot we still don’t really know about how jets work in the X-ray band.”

The Centaurus A galaxy was discovered as early as the mid-1800s, but it wasn’t until a century later that its twin jets came into view of then-new radio telescopes. One of the jet’s northeastern side points toward Earth, while the other, called the counterjet, faces southwest and is significantly fainter, according to the study.

Astronomers know that black hole jets are fueled by material swept up by the cosmic behemoths and expelled before it can reach the event horizon, which is the boundary around black holes that traps everything, including light, for eternity. However, precisely how the material is funneled to the jet is poorly understood; prevailing theory suggests powerful, messy magnetic fields around the black hole and the behemoth’s spin itself may be important contributors.

In addition to how the observed knots may have formed, researchers are also puzzled over their changing brightness. During the two decades, from 2002 to 2022, a knot became brighter while another faded. Back in 2009 astronomers spotted the same trend in jet knots blasted by a monster black hole in the center of M87 galaxy, which resides roughly 55 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Virgo. For reasons unknown, those knots brightened over several years to the point that they outshined even the galaxy’s brilliant core before fading into the darkness of space.

Forthcoming investigations into the jets of Centaurus A and other galaxies could reveal whether the knot’s varied speeds and brightness is an intrinsic behavior of the jet as it blasts away from the black hole, or an external obstacle, such as interstellar material.

“A key to understanding what’s going on in the jet could be understanding how different wavelength bands trace different parts of the environment,” Bogensberger said in the statement. “Now we have that possibility.”