10 of Futurama’s smartest science references and gags (Image Credit: Space.com)

When “Futurama” first beamed onto planet Earth in 1999, it was no surprise that a TV series co-created by “The Simpsons” mastermind Matt Groening was packed with smart references to pop culture and current affairs. But beyond the conveyor belt of gags about “Star Trek” and the state of planet Earth, the show’s team of writers — many of whom are science graduates — have also managed to squeeze in plenty of ingenious references to physics, mathematics and other branches of the sciences.

Below we’ve picked out √100 (okay, 10) of the best science references from “Futurama”‘s quarter century on our screens — running the full gamut from simple sight gags, to jokes directed squarely at the finest mathematical minds in the galaxy.

Oh, and because the numbering system for “Futurama” seasons hasn’t always been as constant as ∏, we’ve stuck with the nomenclature currently used by Hulu (US) and Disney Plus (UK).

1. Number theory

If there’s a mathematical equivalent of the pun, then “Futurama” has turned the play on numbers into an artform. These have varied in complexity across the show’s run, ranging from relatively simple sight gags (Route 66 rebranded as √66, 7-Eleven reinvented as 711) to jokes only mathematicians will understand.

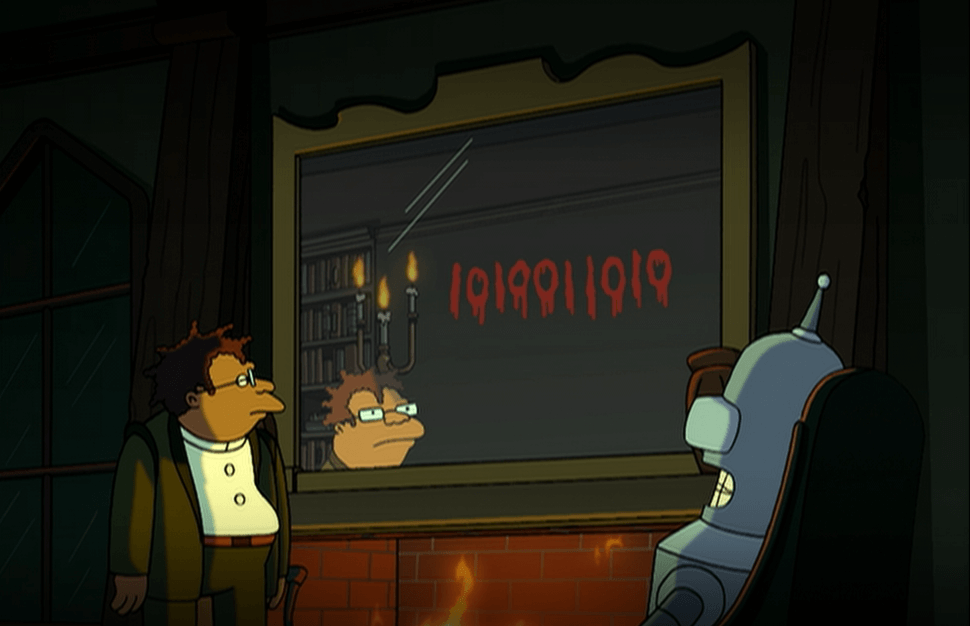

For example, when season two’s horror pastiche “The Honking” whisked Bender away to a “Shining”-esque haunted house, the number he saw in the mirror was 1010011010 — fairly innocuous in base 10, but 666 (aka the number of the Beast) in binary.

You also have to look closely at the name of the nightclub in season six episode “Rebirth” to truly understand its relevance — Studio 122133 is just another way of expressing Studio 54, the legendary New York night spot.

2. Get with the program

While resident robot Bender has generally made an effort to talk like a human, “Futurama” has also referenced vintage computer languages.

Bender used Olde FORTRAN Malt Liquor as a power-up in the PlayStation 2 “Futurama” game, and the brand’s still going strong in 3023 when Professor Farnsworth takes a swig in season 11 episode “I Know What You Did Next Xmas”.

BASIC also gets a look in. In a gag that will engage the nostalgia circuits in many a veteran programmer, the sign on the wall of Fry and Bender’s apartment says:

10 HOME

20 SWEET

30 GO TO 10

In season four’s “Kif Gets Knocked Up A Notch”, meanwhile, Kif creates a holodeck pony for his beloved Amy, programmed using “four million lines of BASIC” — an endeavour that must have taken considerable time and effort.

But perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that a show set in the 31st century is so fascinated by retro computing. Season one episode “Fry and the Slurm Factory” revealed that the 6502 processor used in the first Apple II computer — way back in 1977 — can also be found in Bender’s head.

3. Light speed-plus

Albert Einstein‘s theories of relativity have long been fundamental to our understanding of the universe, but the fact that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light is a massive inconvenience to writers of science fiction. Some storytellers get around the problem by warping or bending space (see “Star Trek” and “Dune”), while others send spacecraft into an alternative “hyperspace” dimension (see “Star Wars” and “Babylon 5”) to condense epic journeys between stars into the runtime of a movie or TV episode.

Few franchises have been as creative as “Futurama”, however, where it turns out that scientists worked out how to increase the speed of light in 2208 — a cunning ruse that makes faster interstellar travel possible without violating the rules laid down by Einstein. The concept is nearly as ingenious as the afterburners on Professor Farnsworth’s dark matter engines, which run at an impressive 200% efficiency.

4. Taxi!

From the 1138 that keeps cropping up in “Star Wars” to the A113 that’s ubiquitous in Pixar movies, pop culture loves using numbers as in-jokes. While those two examples are, respectively, references to “THX-1138” (George Lucas’s debut movie) and a classroom at CalArts (California Institute of the Arts), the 1729 that’s a regular guest star in “Futurama” is a big deal in mathematics.

In the show, Bender is his mother’s 1729th son; the serial number of the Nimbus, Zapp Brannigan’s ship, is BP-1729; and one of the parallel realities in season four’s “The Farnsworth Parabox” is Universe 1729.

Despite its seemingly non-descript nature, 1729 is the most famous “taxi cab” or Ramanujan-Hardy number, the smallest number that can be expressed as the sum of two positive integer cube numbers in more than one way — in this case, 13 + 123 and 93+103.

1729 isn’t the only taxi cab/Ramanujan-Hardy number to cameo in “Futurama”, either, because 87,539,319 (which can be expressed as 1673 + 4363, 2283 + 4233 and 2553 + 4143) features on an actual taxi cab in 2007 movie “Bender’s Big Score”.

5. A quantum finish

Whether they’re using goal-line technology or cameras of mind-boggling sophistication, sports administrators are always looking for new ways to make impossibly tight margin calls. “Futurama” suggests this will still be the case a thousand years from now.

In season three episode “The Luck of the Fryish”, electron microscopes are used to separate a dead heat in a horse race at Flushing Downs. Unfortunately, not even quantum levels of accuracy are enough to stop punters from disputing the result. “No fair!” moans Professor Farnsworth. “You changed the outcome by measuring it!”.

It’s a neat practical demonstration of the Observer Effect, as a phenomenon that had already doomed Erwin Schrödinger’s infamous cat also ruined Farnsworth’s chances of winning big at the bookmakers.

6. The ultimate strip

Any schoolkid can create a Möbius strip with a piece of paper and some glue, but the mathematics behind these single-sided loops is truly intriguing.

In season 10 episode “2-D Blacktop”, Leela and Professor Farnsworth race each other around a Möbius dragstrip, and the circuit’s unconventional geometry proves rather confusing when the competitors reach the finish line — on the wrong side of the track.

“[There’s] two more laps,” says a rival street racer. “You forgot on a Möbius strip two laps is one lap.”

“You kids and your topology,” laughs Dr Zoidberg in a refrain that was probably echoed by mathematicians everywhere.

(It’s worth noting that the science here is considerably more plausible than the ridiculous high-octane physics that powers the “Fast & Furious” series.)

7. Infinite screens and nothing on

It’s an unfortunate fact of 21st century life that there are many more movies and TV shows than we’ll ever have time to watch. Spare a thought, then, for the residents of 31st century New New York, who are faced with literally infinite choice every time they head to the flicks.

The ℵ0 in the name of futuristic cinema chain Loew’s ℵ0-Plex refers to aleph-null, which — in mathematics — is the smallest infinite cardinal number. So while the screen count is on the low side when it comes to infinities, even the most completist cinephiles will struggle to reach the end of a playlist that includes “It Came From Planet Earth”, “Planet of the Clams” and “Quizblorg, Quizblorg”.

8. Black hole fun

Like Bart’s weekly words of blackboard wisdom in “The Simpsons”, the caption in “Futurama”‘s opening credits changes from episode to episode.

“What happens in Cygnus X-1 stays in Cygnus X-1” (from season seven’s “The Prisoner of Benda”) may look like a simple sci-fi-themed riff on the famous Las Vegas catchphrase, but there’s more to the destination than initially meets the eye.

When it was identified in 1971, X-ray source Cygnus X-1 was widely regarded as the first black hole ever discovered, and subsequently became the subject of a bet between physicists Stephen Hawking and Kip Thorne (famously the scientific consultant on “Interstellar“). Hawking bet against black holes existing in this particular region of space, explaining in “A Brief History of Time” that “[the bet] was a form of insurance policy for me. I have done a lot of work on black holes, and it would all be wasted if it turned out that black holes do not exist. But in that case, I would have the consolation of winning my bet.”

Hawking did eventually concede the wager, which won Thorne a year’s subscription to “Penthouse” magazine. Had Hawking won, he’d have received four years of satirical British mag “Private Eye”.

9. Raise the proof

This is another entry from “The Prisoner of Benda”, and a rare example of pop culture not just referencing mathematics but enhancing it, too.

As well as being responsible for many of “Futurama”‘s most memorable episodes, regular writer Ken Keeler holds a PhD in applied mathematics from Harvard. He applied this knowledge to devise an actual mathematical theorem (based on group theory) to explain a key plotline of the episode — namely that however many mind swaps are made between two characters, it’s possible to ensure that everyone’s mind is eventually reunited with its original body.

This scenario will almost certainly never come up in real life, of course, but it’s comforting to know someone’s considered the mathematics, just in case.

10. Another day in paradox

At times real-life mathematics can be even stranger than the ideas “Futurama”‘s writers come up with on screen.

In season eight episode “Benderama”, Professor Farnsworth invents the Banach-Tarski Dupla-Shrinker, a machine capable of creating two smaller copies of an object. The professor’s motivation is simple — he wants smaller sweaters and more of them because he’s shrinking and getting colder — but Bender sees the machine as an opportunity to duplicate himself. These duplicates then duplicate themselves into more duplicates, who duplicate themselves (ad infinitum) until the Earth is overrun by millions of tiny nano-Benders.

The actual mathematics of the Banach-Tarski paradox is even weirder — and counterintuitive — than its fictional counterpart. The theorem states that a solid, three-dimensional ball can be broken down into a finite number of discrete elements that can then be reassembled to create two identical copies of the original ball. Presumably the show’s writers surmised that unleashing infinite Benders of the same dimensions was too weird, even for “Futurama”‘s science-literate audience.

Season 12 of “Futurama” debuts on July 29 on Hulu in the US and Disney Plus in the UK, where you can also watch all of the previous seasons.