Alien: The Xenomorph life cycle explained (Image Credit: Space.com)

Alien: Romulus promises to cleverly mix the horror thrills of Ridley Scott’s original 1979 masterpiece with the action-heavy 1986 sequel by James Cameron. If you’re currently in the mood to get back into the iconic sci-fi series before it arrives, you’ll want to read our in-depth examination of the Xenomorphs’ many life stages and forms as seen in the movies.

The Alien movie franchise will soon expand with an Alien TV series too, which could keep the tradition of each creative team bringing their own sensibility to the universe alive. First, however, we’ve yet to see how Romulus strikes a balance between the first two classics while hopefully closing some of the gaps in the canon opened by Scott’s Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, two divisive but fascinating prequels full of big ideas and bold swings.

Whether you’re a newcomer to the Alien franchise or someone looking to get a full refresh before returning to theaters this summer, we recommend looking at our Alien movies in order and Alien movies ranked lists. There’s also out best Alien games of all time list too, if you want to get in on the scares.

Egg

Of course, we can’t start this exploration of the Xenomorph life cycle without the species’ most basic form: the leathery (and rather large) eggs that were first seen in that memorable scene of the 1979 original. Characterized by their remarkable size and the ‘goo’ that covers them, as well as their four-lobed opening at the top, the alien eggs can seemingly lie dormant and wait for potential hosts (human, Engineer, or otherwise) for decades and maybe, given the Xenos’ resilience and adaptiveness, even centuries.

Since the planned third entry of Scott’s prequel trilogy never came to fruition and Romulus is taking the story to the period between Alien and Aliens, we don’t really know the exact origin of the Engineer ship and the eggs inside it that the crew of the Nostromo found on LV-426 in the year 2122.

We do know that Queens typically produce the eggs, but the original movie’s novelization included the concept of ‘eggmorphing’ as the ultimate fate of Dallas and Brett, who’d been captured and cocooned by the Xenomorph roaming the Nostromo. The scene was reinstated partially in the movie’s Director’s Cut, and the eggmorphing process popped up again in other secondary Alien works, which is why many fans consider it a canonical ability of the species to reproduce and start the creation of a hive in the absence of a Queen.

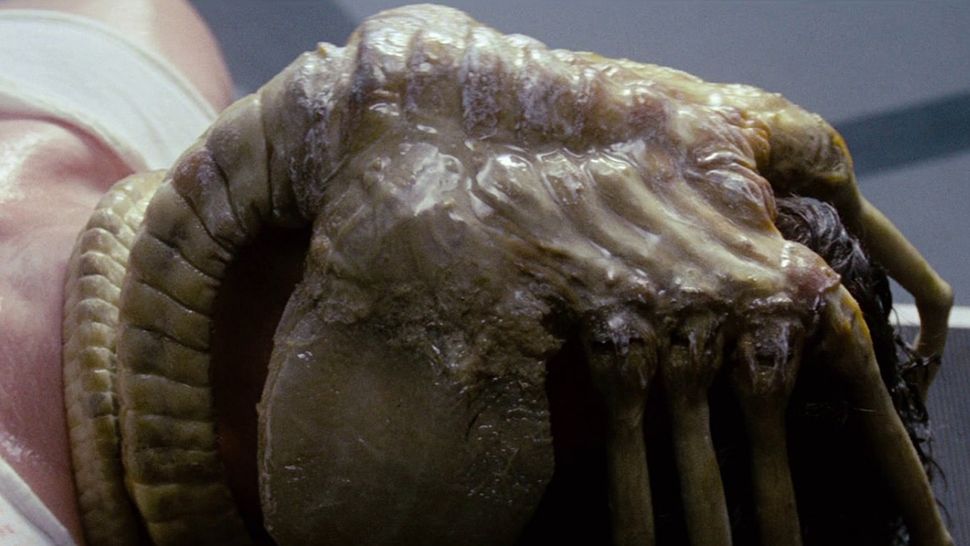

Facehugger

Almost as iconic as the Xenomorph’s main life stage is its facehugger form, which has become a mainstay of the movie series. Any living being that is caught by one of these is done for, as no non-lethal way to extract Xeno embryos and the ensuing chestbursters has been shown in the movies.

The crab and spider-like facehuggers, whose fast movement and jumps are unsettling enough on their own, attach to a victim’s face and release a strong paralytic chemical before latching on to their head with the legs. After the Xeno embryo is in place and can sustain itself inside the host, the facehugger detaches and dies. Any attempt to remove facehuggers is almost guaranteed to be fatal, as the parasite responds by tightening its grip on the victim and its acidic blood is as strong as that of an adult Xenomorph.

This stage of the life cycle is only skipped by the large Predalien, which was birthed from an impregnated Predator and first seen in Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem. That creature could directly produce and inject Xeno embryos into its victims, acting as the resulting hive’s Queen.

Chestburster

The chestbursters represent the most unpredictable and fascinating stage of the aliens’ life cycle, as what happens during this part of the evolution process defines the traits that shape the resulting Xenomorph. It seems that chestbursters are actually grown from the biological material of the hosts, which would explain why the resulting Xenos retain physical traits and even abilities from the living beings that unwittingly birth them later.

Typically, a chestburster violently erupts from the chest of its host, hence the nasty and disturbing nickname. It’s at this stage when the Xenomorphs are most vulnerable, yet chestbursters are fast and silent once they escape their hosts’ bodies. Once a secure location to cocoon and grow has been found, it’ll become an adult Xenomorph in just a few hours.

Drone

The terrifying Xenomorph drone is the iconic alien in its most basic, recurrent, and memorable form — an almost perfect organism that’s as lethal as it is industrious. Its main objective is to either grow or establish a hive, and will seek new hosts for gathering and impregnation, yet it can also kill any immediate threat to its integrity or the hive. Hosts other than humans produce different types of drones, such as the ‘runner’ birthed from a quadrupedal mammal on Fiorina 161 (Alien 3).

Drones are stronger and faster than a human, and are also extremely good climbers and jumpers. Moreover, like other adult Xenos, they appear to be able to survive even in the void of outer space. Its weapons are a piston-like tongue that is tipped with a second set of jaws, large claws, and the lance-like tip of its long tail. Even in death, they’re savage, as any open wound will eject highly pressurized acid blood.

Warriors (and other adult Xenomorphs)

Once a hive is big enough, many drones will evolve into warriors, similar but more resilient Xenomorphs, often characterized by their ‘ridged’ heads. There are other subtypes which are tasked with more specific activities within and outside the hive.

Much like drones, warriors and other subtypes retain the major DNA traits inherited from the hosts that birthed them, which means a Xenomorph hive and its population will be profoundly defined by the ecosystem that birthed it.

Praetorians could be considered an entirely different category, as they’re considerably larger than other adult Xenomorphs (but still smaller than Queens). According to non-movie works, a handful of warriors are ‘chosen’ by the Queen and fed royal jelly, which leads to their transformation into the horrifying but majestic (due to the crown-like, flat crests) monstrosities tasked with protecting the leader of the hive.

Queen

The big boss and apex of the species is the Xenomorph Queen. Her highly iconic shape, coupled with the absolutely massive size for a terrestrial being, instantly granted Aliens’ main villain a firm place among the best-ever monsters put on the big screen.

Queens are much larger and stronger than drones, warriors, and even praetorians. However, they’re vulnerable while they’re attached to the giant ovipositor that it uses to continuously lay eggs. They’re not very fast, but can still surprise any unfortunate soul that isn’t quick enough on their feet if they get agitated or are under extreme threat.

Video game and comic books have also introduced Empresses (Queens capable of ruling over several ‘regular’ Queens and their respective hives) and even the Queen Mothers, the absolute peak of the Xenomorph species, gigantic in size and far more intelligent than Empresses and Queens. As depicted in such works, the Queen Mothers can control all the Xenomorphs on a continent or planet. To this day, these definitive Xeno stages haven’t been shown (or even referenced) in the movies, making them ‘extended universe’ additions.

Beyond the Xenomorph

Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, especially the former, put much of the focus on the Engineers and their other bioweapon efforts. Like it or not, the Xenomorphs in the current on-screen canon (which may clash with the Alien vs. Predator movies) are the product of the Engineers’ experiments, much like mankind on Earth. The main weapon found by the unsuspecting humans and their Michael Fassbender-looking synthetics on LV-223 and Planet 4 was the ‘black goo’ that both created and destroyed life forms in unpredictable ways.

According to David’s studies and experiments on Planet 4, an Engineer homeworld, the pathogen’s primary purpose was to ‘cleanse’ planets of non-botanical life forms, yet the weapon proved to be more unstable than originally thought by its creators. Incompatible hosts were killed, and other beings were either mutated into monsters or became hosts for parasitic organisms similar to the Xenomorph facehugger. Unsurprisingly, those parasites also impregnated any living being that was big enough and produced alien lifeforms like the ‘Deacon’ on LV-223 and the ‘Neomorphs’ on Planet 4, which were remarkably close to the Xenomorphs as we know them.

While the main implication in Alien: Covenant is that David himself created the Xenomorph as seen in Alien and beyond after tinkering with the pathogen and the Engineers’ scientific tools and knowledge, there are marked differences between the drones seen in the prequel and the one born from one of the eggs in LV-426. Moreover, the novelization of Covenant and some visual elements in the movie itself and the previous one offered enough wiggle room to consider that David could have simply revitalized an old Engineer bioweapon to create his own ‘offshoot version’ of the creatur.

Word on the street is that Alien: Romulus might offer some answers for the remaining questions that the third Alien prequel was going to tackle, so maybe we’ll end up with canon in a better place after Fede Álvarez’s movie lands in August. However, the Alien TV series is supposedly set in a not-so-far future and on Earth, so chances are the flimsy lore will get even more complicated for diehard fans.