There’s an Extremely Stupid Reason NASA Scientists Can’t Study China’s Amazing New Moon Rocks (Image Credit: futurism-com)

“China welcomes scientists from all countries to apply according to the processes and share in the benefits.”

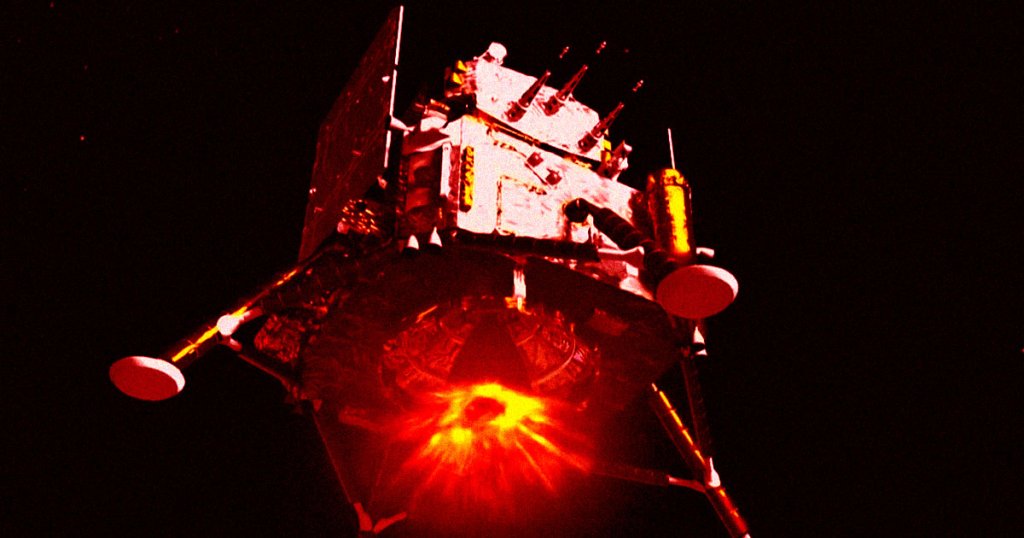

Earlier this week, China’s Chang’e 6 lunar probe landed in Inner Mongolia, delivering the first-ever samples collected from the far side of the Moon.

The mission has the international scientific community excited — the far side of the Moon, which permanently faces away from the Earth, remains mysterious, with only China having touched down on its surface so far.

But there’s one nation that will be barred from poring over the exceedingly rare samples: the United States.

That’s because the US enacted a law called the Wolf Amendment in 2011, which prevents NASA from using government funds to cooperate directly with China.

The controversial piece of legislation has turned into a hot-button topic, with a potential repeal becoming a “political football, tossed between hawkish factions eager to paint China as an emerging adversary in space and less combative advocates wishing to leverage the country’s meteoric rise in that area to benefit the US,” as Scientific American wrote in 2021.

“The source of the obstacle in US-China aerospace cooperation is still in the Wolf Amendment,” China National Space Administration vice chair Bian Zhigang told reporters this week, as quoted by the Associated Press. “If the US truly wants to hope to began regular aerospace cooperation, I think they should take the appropriate measures to remove the obstacle.”

Chinese officials revealed today that its Chang’e 6 rover returned just shy of two kilograms (4.4 pounds) of samples from the lunar far side. While it’s far from being the largest sample to have been returned from the Moon — NASA’s Apollo 16 mission returned a whopping 26 pounds of rock in 1972 — it’s the first sample taken from the far side of the Moon.

The far side’s extremely rocky and crater-filled surface makes it an extremely challenging environment to explore. Its distinctive characteristics have long puzzled scientists.

Now, China’s groundbreaking Chang’e 6 mission could finally provide some answers. For one, the samples could shed light on the kind of local resources future space explorers could make use of, including water ice.

While China has cooperated with a host of countries for its Chang’e 6 mission, the US likely won’t be part of the picture as scientists analyze the samples in a lab due to the Wolf Amendment.

However, that doesn’t mean China isn’t open to the idea.

“China welcomes scientists from all countries to apply according to the processes and share in the benefits,” China National Space Administration director of international cooperation Liu Yunfeng told reporters.

The Wolf Amendment, named after former US representative Frank Wolf, prohibits NASA from using government funds to cooperate with the Chinese government — unless it has certification from the FBI that such collaboration poses no threats to national security or risks inadvertently leaking space-related tech or data.

It was designed to pressure China into improving its human rights records, desired changes that experts say haven’t materialized over the past 13 years.

Instead, China has made considerable advances, with its space agency sending multiple rovers to the lunar surface over that time, and launching its own space station in less than two years.

But there’s still a small chance NASA could help China study its samples from the far side of the Moon. In a rare case of US-Chinese cooperation last year, NASA urged scientists to apply to study samples returned by the country’s Chang’e 5 mission to the near side of the Moon in 2020.

At the time, the space agency announced it had provided the necessary certifications to Congress to prove there was no risk of transferring tech or data to China.

China is currently in a strong bargaining position. With almost half a dozen successful trips to the lunar surface in recent years, it’s outpaced NASA’s efforts considerably. The US agency’s last trip to the surface of the Moon was over half a century ago — and it still has a long road ahead of it to change that.