New moon of June 2024 tonight lets Saturn, Mars and Jupiter shine (Image Credit: Space.com)

The new moon of June 2024 occurs tonight, making this a great night to get and enjoy a sky free from the glare of the moon.

New moons occur about every 28.5 days, as the moon passes between the sun and Earth on its journey around its orbit. More formally, a new moon is when the sun and moon share the same celestial longitude, a projection of the Earth’s longitude lines on the sky. This is also known as a conjunction.

The time of a new moon according to local clocks depends on when the moon gets to a certain point in its orbit; that means the hour changes with one’s time zone; it is independent of one’s latitude. The new moon occurs June 6, at 8:38 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time (1238 UTC), in New York, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. The new moon is at 7:38 a.m. CDT on June 6 in Chicago, and 5:38 a.m. PDT in Los Angeles. In Europe and points east the new phase occurs later in the day; 1:38 p.m. in Paris, and 2:38 p.m. local time in Istanbul.

Related: Night sky, June 2024: What you can see tonight [maps]

If the plane of the moon’s orbit were exactly lined up with that of Earth’s orbit, the moon would pass in front of the sun every month and create a solar eclipse (which would always be visible in the tropics). However, the moon’s orbit is inclined to the plane of Earth’s orbit by about five degrees; it will “miss” the sun this time. (The next solar eclipse is on Oct. 2 and will be visible in the southeastern Pacific Ocean and southern South America).

You can prepare for the next new moon with our guide on how to shoot the night sky. If you need imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography to make sure you’re ready for the next eclipse.

And if you’re looking for binoculars or a telescope to observe the stars or planets of the night sky, check out our guides for the best binoculars and best telescopes.

Visible planets

On the night of the New moon (June 6-7) the sun sets in New York at 8:24 p.m. local time; it will be similar to other mid-northern latitude cities such as Chicago (8:23 p.m.) and Sacramento (8:28 p.m.).

The naked-eye planets won’t be visible until after midnight; they are all “morning stars” in early June. The first to rise is Saturn, at 1:32 a.m. in New York; Saturn is in the constellation Aquarius, and will stand out as it is much brighter than the surrounding stars. Saturn will be at its highest in the sky by about 7 a.m.; but at sunrise it will be a full 37 degrees above the southeastern horizon.

Mars follows at 3:01 a.m., and it will be below and to the left of Saturn. By sunrise, Mars will be about 27 degrees high in the east. Mars is in Pisces, the fish, another relatively faint group of stars that allows the red planet to stand out.

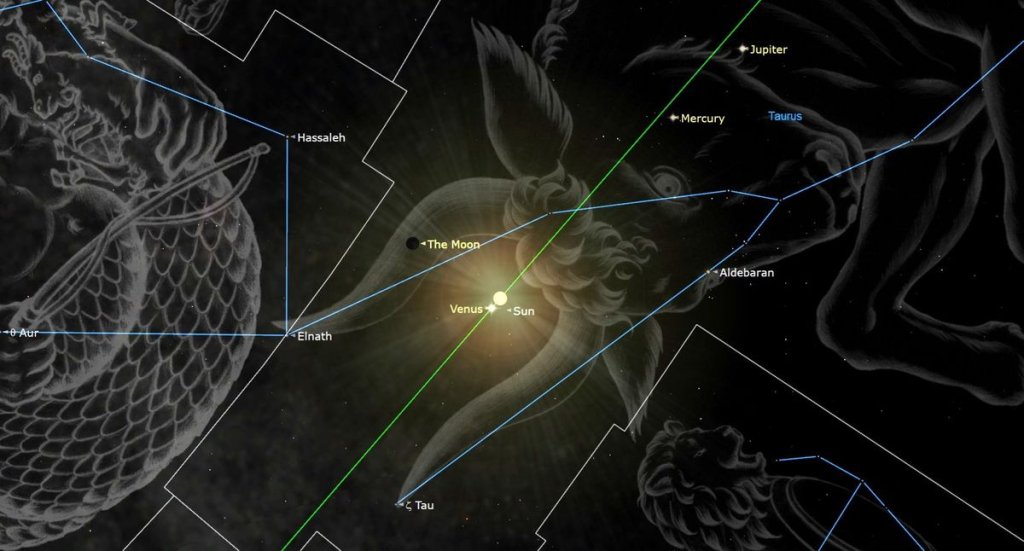

Jupiter rises after that at 4:38 a.m. local time. Sunrise in New York is at 5:25 a.m. and Jupiter will only be about 8 degrees high, so catching it will require a clear view of the horizon and a clear sky. Mercury and Venus will be lost in the solar glare; they will emerge in the evening sky in July.

In the mid-Southern Hemisphere latitudes June is the month of the winter solstice; the nights are longer; in Montevideo, for example (where the new moon is at 9:38 a.m. June 6) the sun sets at 5:40 p.m. local time. As the three visible planets are all currently below the celestial equator, they appear much higher in the sky than in the Northern Hemisphere.

Saturn, for example, rises at 12:42 a.m. local time almost due east, followed by Mars, a bit further to the north, at 3:53 a.m. If one is facing northeast by 4:30 a.m. one will see Saturn a full 44 degrees high and Mars at 8 degrees. Jupiter rises at 6:39 a.m., a little more than an hour before sunrise which is at 7:47 a.m. on June 7; a half an hour before the sun comes up it is about 6 degrees high so, as for Northern Hemisphere sky watchers, it’s a challenging target. Montevideo is at latitude 34 degrees south; the times for celestial bodies to rise and set will be similar in locations such as Cape Town and Sydney.

Constellations

In mid-northern latitudes, it’s close to the longest days of the year; skies don’t get fully dark until about 9:00 p.m. in New York City or Chicago. By 10 p.m., looking west, one will see Leo the Lion moving towards the horizon; the constellation will be about a third of the way towards the zenith. Its brightest star, Regulus, will be at the bottom of the characteristic sickle or reversed question mark that is the Lion’s head, and looking left and upwards one will reach Denebola, the end of the Lion’s tail; look for a right triangle of stars with Denebola at the point on the left, and the right angle on the bottom to the right.

As one turns eastward towards the south one sees Spica, the alpha star of Virgo the Virgin, about 36 degrees high and recognizable by its whitish hue compared to the more yellowish Denebola.

In the East, one will see Vega, Altair and Deneb, the three stars of the Summer Triangle. The easiest to spot is Vega, or Alpha Lyrae, (the Lyre), the legendary instrument of Orpheus. It is the first of the three to rise and thus highest in the sky; it is bright enough to be distinct even in city locations. By 10 p.m. it is about 40 degrees high in the east-northeast. Look towards the horizon and to the left and one encounters Deneb, the tail of Cygnus the Swan, about 24 degrees high. Altair will be the one closest to the horizon (it may be obscured by buildings or trees) and nearly due east, about 10 degrees high. Altair is the brightest star in Aquila, the Eagle, and is often called the Eagle’s eye, with the two fainter stars close on either side of it marking the bird’s head.

An asterism in the Swan is the Northern Cross; if one draws a line from Deneb to the right one encounters Sadr, the central part of the cross, and continuing the next bright star is Albireo, Cygnus’ second-brightest star. The crossbeam of the cross goes through Sadr at a 90 degree angle.

The Summer Triangle is also a good direction finder; the narrowest point of the triangle always faces southward, especially as it gets higher in the sky, much as another asterism, the Big Dipper points north.

The Big Dipper, meanwhile, is part of Ursa Major, the Great Bear. If one turns from the Summer Triangle to the left (northward) halfway across the sky, one will see the Big Dipper, west (to the left) of the North Star, Polaris. The Dipper is vertical, with the bowl pointing down and the top of it facing right. The two stars that point to Polaris, Dubhe and Merak, are on the lower side of the bowl, with Dubhe closer to Polaris. Opposite Polaris from the Dipper, and low in the northern sky, is the bright “W” shape of Cassiopeia, the queen of Aethiopia. Cassiopeia’s husband, the king Cepheus, is visible right above Cassiopeia; Cepheus is a square topped by a triangle that points roughly towards Polaris.

Following the handle of the Dipper one can “arc to Arcturus” –a sweeping motion along the curve of the handle gets you there, to the brightest star in Boötes, the Herdsman, high in the southwest, nearly at the zenith. Continuing on the “arc” one reaches Spica, in Virgo. Further to the left – now you’re moving eastwards and towards the south – is Antares, a bright red star that is the “heart” of Scorpius, the Scorpion. Scorpius’ claws are to the right of Antares and the rest of the body snakes towards the horizon; in some locations further north such as London or Montreal some parts of the constellation never rise; Scorpius doesn’t get fully above the horizon in New York until about midnight.

Above Scorpius from dark-sky sites is the fainter (but much larger) constellation Ophiuchus, the Serpent Holder or Healer. Ophiuchus can be recognized by a long trapezoid of medium-to-faint stars that extends above Scorpius; prior to midnight he will appear to be lying on his side. On either side of Ophiuchus are the constellations Serpens Caput and Serpens Cauda, the head (Caput) and the tail (Cauda) of the serpents that Ophiuchus holds.

If one draws a line between Arcturus and Vega, one encounters two constellations. One is Corona Borealis, the Northern Crown, just to the east of Boötes, and east of that is the “keystone” – the four stars that make up the body of Hercules.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the sky is dark enough to see stars by 7 p.m. in mid-southern latitudes. Looking west one can see Sirius, or Alpha Canis Majoris (the Big Dog), the brightest star in the sky, moving towards the horizon; with the other stars in the constellation it looks almost as if the dog is walking towards the west; in the southern latitudes the Dog is right-side-up as opposed to vertical as it is in the Northern Hemisphere.

Turning towards the southwest one will see Canopus, the brightest star in the Carina the Ship’s Keel, about 35 degrees above the horizon. Looking a bit east of south, at an altitude of about 60 degrees one can see the Southern Cross, a compact group (it happens to be the smallest of the 88 currently recognized constellations). Just to the left of it will be Alpha Centauri (Rigil Kentaurus), the brightest star in Centaurus the Centaur and the Sun’s closest stellar neighbor. Alpha Centauri is usually seen as one of the Centaur’s front hooves, and just above Alpha Centauri is a slightly less bright star Hadar, marking the other.

Scorpius will be in the east-southeast about 25 degrees high, though in the Southern Hemisphere the Scorpion appears to be lying on its back; the “claws” are to the left and the tail is to the right.

The South Celestial Pole is in the constellation Octans, the Octant. Octans is faint, and there is no southern “pole star,” so one has to locate the pole uing a system of “pointers.” The Southern is useful here; one draws a line along the two stars forming the center part of the Cross about five times the distance between them and you reach the South Celestial Pole; another method is to use the Centaur and Eridanus the River, which rises after midnight at in mid-southern latitudes. One can draw a line from a point halfway between Hadar and Alpha Centauri to another bright star, Achernar, the end of the River. (Imagine a “T”). The south celestial pole is at the halfway point between the two constellations.