WORLD: Re-Optimizing the Forces (Image Credit: airandspaceforces)

Leaders Roll Out Big Changes for Air Force & Space Force

By Tobias Naegele and Chris Gordon

AURORA, Colo.

A

ir Force and Space Force leaders rolled out sweeping changes to the services’ organization, manning, readiness, and weapons development at the AFA Warfare Symposium in February, aiming to ratchet up readiness and gain a warfighting edge in the face of intensifying great power competition with China.

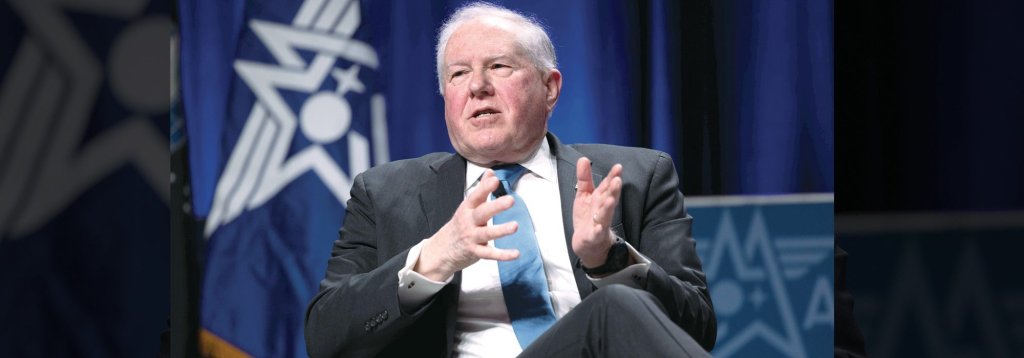

Secretary Frank Kendall, Acting Undersecretary Kristyn Jones, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin, and Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman detailed 24 action items and an aggressive schedule for implementation in a joint presentation to open the conference.

“All of these are intended to make us more competitive and to do so with a sense of urgency,” Kendall said in a speech unveiling the changes.

Citing the prospect of conflict—either through a military move by China on Taiwan or miscalculation that could escalate—Kendall said it is well past time to make changes. “We are out of time,” he repeated several times during his remarks.

The Air Force will reorient its major commands to focus on combat readiness, peeling off their requirements and weapons development functions and consolidating those into a new Integrated Capabilities Command. Headed by a three-star general and reporting directly to the Chief and Secretary of the Air Force, it becomes a new power center for current and future programs.

The idea is to have leaders be able to define requirements and build programs without having to manage a competing focus on today and tomorrow.

“We need to both be ready today with the force that we have. We need to approach that with a sense of urgency,” Allvin said. “But we also need to update—re-optimize, dare I say—the processes, the policies, the authorities, and in some cases, the structure to be competitive for the long term. We need to do both of these at the same time. And that’s the goal of these decisions.”

The Space Force will create a new Space Force Futures Command with a similar objective.

It will be the Space Force’s fourth Field Command, the service’s equivalent to the Air Force’s Major Commands.

“Over the first four years in the Space Force, we focused on some of the systems … we didn’t really have the mechanisms to evaluate all the other components that have to be in place,” Saltzman said, citing everything from identifying the number of facilities needed to handle classified information to forming the USSF’s operational concepts. “That is what a futures organization can provide for you.”

Planned changes span the services and technologies. Cyber and electronic warfare will be elevated—what is today’s 16th Air Force, the information warfare arm of Air Combat Command, will be elevated to Air Forces Cyber, reporting directly to the Chief and Secretary with responsibility for operational cyber, information, and electronic warfare. It will continue to be led by a three-star general as it is today, but its rise to direct-reporting status suggests added stature and visibility.

Focus on Readiness

Operational Air Force wings will be restructured as “units of action,” with each designated as a Deployable Combat Wing, an In-Place Combat Wing, or a Combat Generation Wing.

Each wing type will be designed and structured for its purpose. Kendall and Allvin want to clarify the blurred lines between operational units and base support and will designate Base Commands to support combat wings and keep bases operating during conflicts or crises. “We’re going to make sure that our deployable wings have everything they need to go fight successfully as a unit,” Kendall said.

In parallel, the Space Force will set up new Space Force Combat Squadrons as its units of action, supporting U.S. Space Command on a rotational basis. Additional Space Force component commands will be established, building on those already created and aligned to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, U.S. European Command, and U.S. Central Command.

Additional Space Component Commands could include U.S. Cyber Command, U.S. Transportation Command, U.S. Northern Command, and U.S. Southern Command.

The reorientation of Air Combat Command, Air Mobility Command, and Air Force Global Strike Command to focus almost exclusively on combat readiness aligns with plans to further refine the Air Force Force Generation (AFFORGEN) Model, which will evolve to support each type of combat wing.

“What has happened over time is that we basically took a lot of what could be headquarters or could be specialized command functions and farmed them out to various Major Commands,” Kendall explained in an interview. “The list of additional duties got pretty long. … And these aren’t core jobs for these commands. What we want fundamentally is to have the major force providers—Air Combat Command, Air Mobility Command, and Air Force Global Strike Command—with responsibilities across the Air Force—focused on readiness for the forces that they have.”

To do that, he and the Chiefs are digging into the Cold War playbook and re-introducing large-scale combat exercises and no-notice operational readiness assessments and inspections. These hallmarks of the days of Strategic Air Command, Tactical Air Command, and Military Airlift Command all but disappeared over the past three decades, as the Air Force focused on supporting continuous operations in the Middle East.

“We’re talking about preparing units of action, which are fundamentally a new construct,” Kendall added of the changes across the Department. “We’re going to make sure that our deployable wings have everything they need to go fight successfully as a unit. And once we have that and they have a chance to train, then it’s reasonable to commit and start evaluating their ability to do that.”

The Space Force will implement new readiness standards for operating in contested environments and when under attack, will introduce its own exercise program nested within the Department-level exercise framework.

The Space Force has heretofore operated as if space was a benign environment, and its leaders are rapidly confronting a future in which the service needs new training—everything from ranges and simulators to large joint force exercises.

“Unfortunately, over the last decade or so what we’ve seen, is now we have to recognize that space is a fundamentally different domain,” Saltzman said. “It is a contested domain. Now if we’re going to be successful in meeting our military objectives, we have to fight for, contest the space domain, and achieve some level of space superiority if we’re going to continue to provide the services that the military needs, that the joint force needs.”

Saltzman likened the shift to transforming the Merchant Marine into the warfighting U.S. Navy.

But “you can’t just tell” the Merchant Marine they need to suddenly be able to fight a war, Saltzman said. “They don’t have the right training; they don’t have the right operational concepts to do the task that they’ve been given.”

The same is true for the Space Force, he said.

“I feel like that’s what we have to embrace,” Saltzman said. “We have to understand that we have to transform this service if it’s going to provide the kinds of capabilities, to include space superiority, that the joint force needs to meet its objectives. That’s the transformational charge that’s at hand.”

Kendall is determined not to let staffs slow-roll these changes. “We’ve got to do this with a sense of urgency,” he said. “The threat is not a future threat, it is a current threat. And it’s getting worse over time. And we’ve got to start orienting ourselves on that and behaving as if we have a deep appreciation for that.”

People

“The Airman Development Command commander will be the sole [individual] responsible for integrating requirements to ensure that, when an Airman goes from one part of our Air Force to another, they don’t need to relearn the systems and the tools, and they can develop faster,” Allvin said. “By integrating this, … we believe we’re going to have a more coherent, single Air Force that can move rapidly to the future.”

Air Education and Training Command will be reborn as Airman Development Command, with a mission to better prepare Airmen for the range of duties they can expect in the more expeditionary future, where Agile Combat Development is no longer just an emerging concept, but the standard operating procedure.

More than just a renamed command, Kendall said the change will also encompass increased responsibility and oversight of programs like NCO academies, “wherever they might be to ensure that we’re getting the type of training across the force that we need.”

The concept of “Multi-Capable Airmen” will be formalized as “Mission-Ready Airmen,” with new skills taught at every level in the training pipeline, beginning in basic training and continuing at wings and at each level of advanced training.

“We’re going to be more deliberate about what training people get so that they are fully prepared to do the jobs we’re going to need them to do,” Kendall said in an interview.

The Air Force will stand up several Air Task Forces this summer, which will go through a full Force Generation cycle, but the wider vision is that wings will be the future unit of action in the Air Force. How fast can these new structures stand up and spread across the force? “My answer to timeline questions is as quickly as we can,” Kendall said. “We need these units now—we don’t need them six years from now or two years from now. We need them now.”

The Air Force will create a new Warrant Officer track for highly skilled IT and cyber talent, enabling those Airmen to not only be paid competitively, but to choose a career path that enables them to focus exclusively on their specialties, bypassing the typical officer leadership track.

“We need mass, people,” Allvin told the audience. “We need to be able to have technical talent of a very specific variety, now and into the future. … We anticipate that will drive that talent in and help us to keep that talent. There’s something specific about this career field, why it’s attractive; and it’s a nice match for a Warrant Officer Program.”

Additional focus on technical tracks for officers and noncommissioned officers is in the works. Warrant officers are approved for IT and cyber “initially,” Kendall said. The Air Force must start somewhere, Allvin explained in his remarks.

“The first thing is, we have to try in this particular career field before we even consider rolling it out across the Air Force to other career fields,” Allvin said.

No plans are in place for the Space Force to adopt warrant officers at least for now.

Weapons Development

The most far-reaching of the changes, however, may be in how Kendall is reorganizing the work of creating and developing new warfighting capabilities. These changes go well beyond the centralization of requirements and integrated development in the new Integrated Capabilities Command and represent the culmination not only of his 30 months as Secretary but nearly 50 years of defining operational requirements and developing weapons in the Pentagon.

A new Integrated Capabilities Office will oversee all capability development for the department, centralizing resource decisions that had previously been determined by individual Major Commands in the Air Force and Field Commands in the Space Force. Two other new offices will be established within the Secretariat to further centralize oversight: an Office of Competitive Activities will oversee and coordinate sensitive programs, and a new Program Assessment and Evaluation Office will apply a common strategic and analytical approach to program performance and associated resourcing decisions.

“We want our fighters and operators to be ready to go to war,” Kendall said in an interview. “That’s what they should be focused on: being ready to go to war now. We want other people thinking about the future.”

Removing oversight of fighter requirements from ACC, for example, or mobility requirements from AMC doesn’t mean disconnecting them entirely from the process, however.

“The current force will certainly have a strong voice,” he promised. “There’s going to be a lot of interaction. “I saw a quote the other day about ‘extreme teaming.’ You know, ‘One Team, One Fight’ has been my mantra since I got here. We’re trying to break down stovepipes as opposed to create new ones. So collaborative processes, involvement of stakeholders—the people who are going to be operating the Future Force have a huge stake in what that future force is. They are not going to be isolated from this. They’re going to be very involved.”

Operators will move into the requirements game, he suggested, and in the future, some experienced operators could move into that game full time at the senior levels. But the key is that the people focused on the future and those focused on the present will not have to split their attention between the two.

Air Force Materiel Command will be reorganized and structured as well, with new and reoriented centers and offices to better oversee critical technical areas:

Information Dominance Center: A new three-star command that will focus on Command, Control, Communications, and Battle Management (C3BM), as well as Cyber, Electronic Warfare, and the enterprisewide information systems and infrastructure that support those and other Air Force and Space Force capabilities.

Air Force Nuclear Systems Center: Another new three-star command, it will expand the existing Nuclear Weapons Center to better support nuclear forces and the command will include a new two-star Program Executive Officer for ICBMs to oversee the overhaul of the ICBM enterprise.

Air Dominance Systems Center: The Life Cycle Management Center will be redesignated and directed to focus on synchronized aircraft and weapons development and support.

Integration Development Office: This organization within AFMC will be responsible for technology assessment and technical expertise to assess the feasibility of new operational concepts and technology insertion.

“We’re going to align the science and technology pipeline,” Kendall said.

Combat Squadrons: USSF’S New Units of Action

Just as the Air Force is defining its “units of action” as Combat Wings, the Space Force is designating “Combat Squadrons” as its units of action. The two are related, but different, reflecting the very distinct operating tempos and conditions of Airmen and Guardians.

Space Operations Command presents forces to U.S. Space Command and other joint force combatant commands, typically as squadrons and deltas. But unlike Air Force units that typically deploy, the Space Force fights from home. So unit commanders are forced to juggle operations—flying satellites, gathering intelligence, conducting cyber work—with all the day-to-day training and administrative issues that others units might leave behind when they deploy.

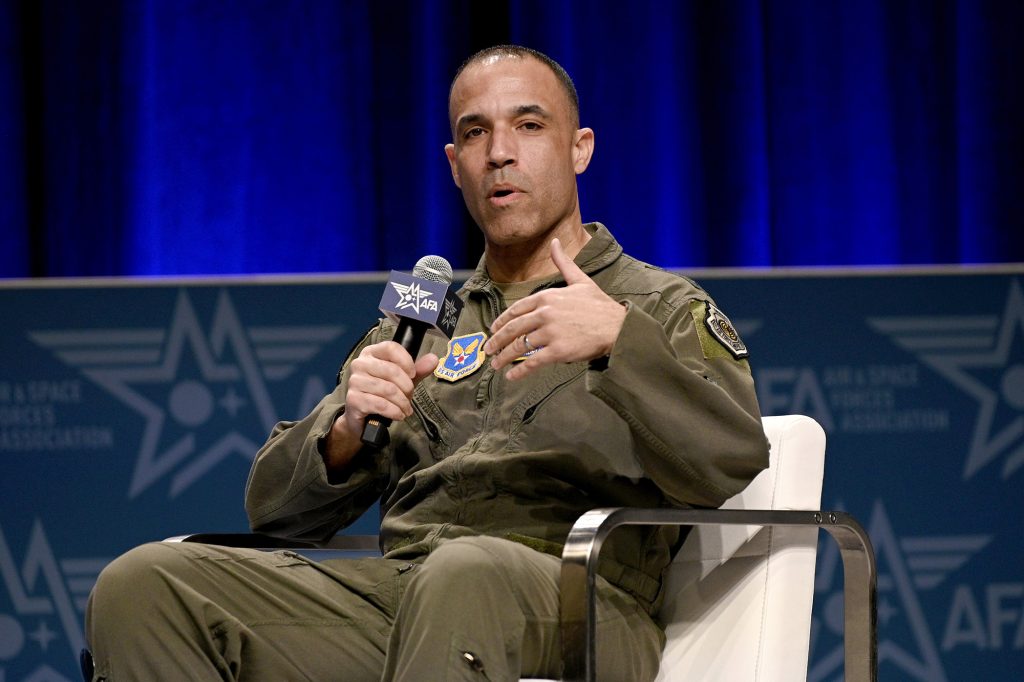

“If I need this number of elements to do the mission 24/7 and I force-present them, well, then you need a number of elements over here to get ready to do that [when the first unit is done],” said Space Forces-Space Commander Lt. Gen. Douglas A. Schiess. “What we’ve done in the past is they’re both doing that all the time. And so that gets to … exhaustion—‘I just came off a shift and now I’ve got to go to training.’ And ‘I’ve got a new person coming in, and I’ve got to get them ready.’”

By designating Combat Squadrons, the Space Force will break down those traditional units into smaller crews and rotate them through phases, using a new Space Force Generation Model. Like the Air Force Force Generation model, AFFORGEN, the new Space Force version will designate phases units must cycle through, demonstrating an advancing level of maturity and readiness as the cycles progress.

This way, when a squadron is presented to SPACECOM, it would no longer work for Space Operations Command, Schiess said. “They work for the Space Forces-Space and they’re doing the mission for that.” During this time, “they don’t have to worry about bringing on new capabilities, they don’t have to worry about training new folks to get ready to feed into the mission to be able to do that,” Schiess said. “They have their crew that is ready to do their mission.”

Brig. Gen. Devin Pepper, vice commander of Space Operations Command, said SpOC intends to follow an “eight-crew model.”

“So five of the crews, whatever system they’re operating, will be in what’s called the combat period, and the other three crews will be in what we call the Prepare and Ready phase,” Pepper told reporters. “Those are all the phases you need to take leave, go to school, do life, so to speak, and then also do the training that you need to get ready to prepare for the combat period.”

The Space Force already follows a similar system for its electronic warfare teams, and it’s similar to the Air Force’s four-phased AFFORGEN system.

The commander of a combat squadron “may be a captain or a lieutenant now who’s responsible for that crew that’s in the combat period,” Pepper said. Meanwhile, regular squadron and delta commanders can focus completely on readiness and training.

When troops aren’t physically deploying, the change is partially just about a mindset shift said Schiess, who compared it to his first job in the Air Force, when he was as a missileer. “I was part of the squadron, I got prepared, I would do training,” Schiess said. “But when I went to the alert facility, I didn’t work for the Air Force anymore, I worked for Strategic Command.”

Yet just as the Air Force is still working on the details of classifying wings, Schiess noted that the USSF is still working on the naming conventions for Combat Squadrons.

“We’re still working through, does that become the 2nd Combat Squadron or 2nd Space Operation?” he said.

Getting Buy-In

The 24 changes outlined Feb. 12 are the culmination of five months of intense effort, during which department leaders took in ideas and inputs from across the services. Among the many proposals, some of the more dramatic ones—such as combining multiple Majcoms into a single Forces Command, much like the Army and Navy—were discarded and refined.

“We worked really hard to make sure everybody’s voice was heard,” Kendall said in an interview. “And we did make adjustments because of things we heard from people. I think there was a widespread perception that change was needed, and what this process has done is identify what exactly we need to do differently. … This has been a mechanism to surface a lot of things that have kind of been on the table, but not necessarily addressed.”

Now comes the hard part—implementing the ideas and making them real.

“We’ve made the major decisions about direction, and we’re going to be working next on all the details of that,” Kendall said ahead of the rollout. “There are still a lot of details to be worked out. It’s going to be a heavy lift. But I think we’re ready to do it. … We’re taking an approach which is designed to overcome bureaucratic resistance. We’re going to put responsible leaders in charge of each of these things. We’ve already figured out generally who they’re going to be. And we’re going to give them the mission of making these things happen.”

None of those changes will need much funding in the near term, Kendall said. Most will be cost-neutral or can be accomplished through the usual process of reprogramming funding from other lines. That’s important, because these changes come too late for the still-not-completed fiscal 2024 budget, as well as the already programmed—but not yet requested—fiscal 2025 budget request. That means that funding for significant changes, like new construction, or large-scale moves, won’t come until the fiscal 2026 budget cycle, which is just beginning to be bent into shape now.

But the Department of the Air Force’s re-optimization efforts have buy-in across the DOD, from Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, Deputy Secretary Kathleen Hicks, and other service secretaries, Kendall said.

“If you’re going to make some major changes in your organization, even if you have all the authorities you need to do them, it’s a good idea to tell your boss before you do,” Kendall said. “I went to both the deputy secretary and the Secretary and basically briefed them, and also briefed my counterparts in the other military departments. There was not a single question asked about the appropriateness of anything we were doing. It was essentially a thumbs-up, you’re on the right path, go get it done. And that’s where we’re going to go.

We’re going to move out on this stuff.”

The Future of Deployment Starts Now

By Greg Hadley and Tobias Naegele

When three Air Task Force elements begin taking shape this summer, they will be laying the groundwork for the new Combat Wings now seen as the Air Force’s deployable “units of action” for future operations—a multi-year process to realign the way the service presents forces to the Department of Defense’s 11 combatant commands.

The aim is to create predictable workup schedules and unit cohesion for Airmen while enhancing the service’s ability to define risk and resourcing requirements to the Joint Staff and Secretary of Defense.

The Air Task Forces forming are the first of at least six planned to form, go through workups together, and deploy as units in fiscal 2026. Each task force will consist of a Command Element and staff, an Expeditionary Air Base Squadron for base operating support, a Mission Generation Force Element to project air power, and a Mission Sustainment Team to enable remote operations under the Agile Combat Employment concept of operations.

“The Air Task Forces … really spoke to an evolution of rotational forces,” Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations Lt. Gen. Adrian Spain said at the AFA Warfare Symposium Feb. 14. “But it is also applicable to standing forces and theater forces. Combat Air Wings speak to the remainder of the force. … What we’re trying to do is build warfighting effectiveness over time with coherent teams.”

Like the ATFs, the Combat Wings will be led by a command element with an air staff to execute command and control; a mission element, such as a fighter, bomber, or airlift squadron, for example; and a combat service support element to run the air base and airfield and care for the needs of wing personnel.

These models seek to replace the “ad hoc,” “piecemeal,” and “crowdsourced” deployment system that evolved over the past 20 years, where small teams pulled from dozens of locations arrived in theater and had to instantly form up and integrate with others they had never met or worked with before.

“Our current paradigm in how we deploy forces often is that we will take one of the mission elements—a fighter squadron or a bomber squadron or a tanker squadron, or what have you, and we’ll take the rest of the forces and sort of crowdsource it from amongst our Air Force, and they will meet in theater,” Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin said. “That does not work against the pacing challenge.”

To better prepare the force for the kind of intense matchups possible should conflict with China arise, Air Force leaders want to create predictable workup schedules and unit cohesion for Airmen while enhancing the service’s ability to define risk and resourcing requirements for the Joint Staff and Secretary of Defense.

To get there will be a multistep, yearslong process.

“This is a kind of spiral development,” said Brig. Gen. David Epperson, director of current operations at Headquarters U.S. Air Force.

Expeditionary Air Bases and Air Task Forces

The move away from individual deployments toward teams has been in the works for years, noted Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations Lt. Gen. Adrian Spain.

“Ten years ago, as a group commander, we were talking about it in terms of … how do we provide more predictability for our units,” Spain said. “Five to seven years ago, we started talking about it in terms of, hey, how do I deploy in teams to build up mutual support, camaraderie, warfighting ethos before I get there.”

In 2021, then-Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. outlined the new Air Force Force Generation (AFFORGEN) model, developed to standardize how teams of Airmen train, certify and exercise their skills, then deploy and reset over a series of four six-month cycles.

For rotational forces, the Air Force launched AFFORGEN with Expeditionary Air Base (XAB) teams, built to provide base support and command and control downrange and to combine with combat elements in theater. The first XAB team deployed to the Middle East about a week after Iran-backed Hamas militants attacked Israel on Oct. 7, setting off an Israeli invasion of Gaza. That air base element, drawn largely from the South Carolina Air National Guard, included a core nucleus that trained together beforehand, plus additional personnel that joined in theater.

“They were able to operate at the speed of trust from the second they got on the ground,” Epperson said.

Air Task Forces represent the next step in that evolution. The first three will take shape this summer, with the goal of at least six that will deploy over the course of fiscal 2026.

“It had to be slow and steady over time to build this up, and the XABs were a natural evolution of that,” said Spain. “And the Air Task Forces were really a clean sheet look from the XABs to figure out a better way to consolidate more, fewer locations, bigger teams, train them together for a distinct period of time before they all went to the same place and executed a warfighting mission.”

Each task force will consist of a Command Element and staff, an Expeditionary Air Base Squadron for base operating support, a Mission Generation Force Element to project air power, and a Mission Sustainment Team to enable remote operations.

Teams of 100 to 250 Airmen will come together during the “prepare” phase of the AFFORGEN cycle, a full year before they’re available to deploy.

“They will train together at that unit,” Epperson said. “They’ll develop those Mission Ready Airmen skills, they’ll learn the different tasks that their entire team is working on.”

Sustaining elements will come together from two to three base locations.

“During the ‘certify’ phase, the vision is that those combat service support teams from different installations will come together and operate during exercises and certification events,” Epperson said. “So the whole team of that ATF will come together at some point multiple times before they deploy.”

Combat Wings

Air Task Forces will be applicable to rotational forces, such as in the Middle East, where the Air Force has built up a large presence over time.

Combat Wings are intended to be deployable operational components built and trained for great power competition. They will be steeped in Agile Combat Employment operational concepts and be seen as operational units of action by the Joint Staff and Pentagon officials.

That’s what’s needed in potential peer conflicts with China or Russia. “Aggregating from 100 different places, literally, as we’ve done in CENTCOM, to descend upon a problem and figure it out when you get to that location, will not work in this environment,” Spain said.

A generation ago, wings were constructed to be able to pick up and deploy to fight anywhere, but over the past 30 years or so, wing and base operations were increasingly consolidated for efficiency. That was prudent then, but must be changed now, Allvin said.

“We need to ensure,” the Air Force Chief of Staff added, “that our Combat Wings are coherent units of action that have everything they need to be able to execute their wartime tasks.”

Combat Wings build on the Air Task Force concept, positioning the entire deployable team in a single location, to the maximum extent possible, living, working, and training together throughout the AFFORGEN cycle.

That will not be possible in every case, however, because not all wings are built or operate the same. So the goal is to sort every operational wing into one of three categories:

Deployable Combat Wings (DCW): Entire wings that can “pick up, deploy, employ, generate, and sustain power in theater,” Allvin said. Spain cited the 366th Fighter Wing at Mountain Home Air Force Base, Idaho, as one potential example, and said such units must be resourced to do so, leaving behind only those capabilities necessary to maintain the base in their absence.

In-Place Combat Wings (ICW): Complete units with command, mission, and support elements that fight from home stations, such as the 341st Missile Wing at Malmstrom Air Force Base, Mont., Spain said. “We need to ensure that where they reside, where they project power from, they have all that they need,” said Allvin.

Combat-Generation Wings (CGW): Wings that “we may not expect to deploy as a wing, but [that] provide combat power that can plug into those combat wings,” Allvin said. That could include elements like command and control; mission elements, such as fighter, mobility, or intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance squadrons; or service support elements that could be “bolted on” to a deployable combat wing. “A combat-generation wing is a little different,” Spain said. “You have elements that would deploy, but the whole wing isn’t going to deploy and it won’t be resourced to do that.”

By design, each DCW and ICW must be sufficiently manned to deploy without leaving a dysfunctional base in its wake that can’t maintain security or keep up facilities needed by those left behind.

“In this future fight, we cannot expect that there will be a benign environment in the installations that are here after the deploying wing is gone,” Allvin said. “We have to be able to not only fight forward, but understand what it takes to continue to defend and operate the base at home.”

The CGWs, meanwhile, provide modularity and flexibility to meet real-world needs.

“What if the combatant commander wants different combinations of airpower to come and support a particular crisis or conflict?” Allvin asked rhetorically. “So let’s say, for example, we’re going to deploy an F-15E wing, that Deployable Combat Wing needs to be ready to take those forces and deploy forward with all the C2 and all the sustainment. But what if we also would like an F-35 squadron, as well? That F-35 squadron should be able to plug into that unit and go. What if we want to use tankers to be able to generate sorties or C-130s to be able to have theater airlift in there? Those mission layers at the squadron layer should be able to plug into this deployable combat wing.”

Combining multiple kinds of aircraft and missions into a standing operating wing proved too costly when the Air Force experimented with so-called “composite wings” in the 1990s. Wings that co-located fighters, bombers, and tankers proved inherently inefficient. But building around a deployable wing such that, for a given deployment, additional squadrons or operating units can be attached gets around that problem—as long as units are built to be plug-and-play compatible.

Deployable Combat Wings are “designed to fit into any C2 structure and fall in on the prevailing command and control apparatus of the combatant commander,” Spain said. “[They have] the elements required to both take orders and to give orders and operate off of mission command and commander’s intent if disconnected.”

A peer rival’s ability to deny satellite connectivity or use cyber to disrupt communications will depend on that kind of independent thinking, and may become the norm under Agile Combat Employment, where smaller teams of Airmen may spread out from a main operating base to complicate an adversary’s targeting. ACE is especially vital to USAF strategy in the Indo-Pacific, an expansive region with hundreds of small islands, all of them within reach of long-range missiles from mainland China.

Building Up to It

Adapting to that future requirement will take time, Epperson said. “We’ll try to do things as efficiently as we can, but realize that it’s not going to be perfect from the get-go,” he said. “It’s going to take some evolution as we move through this process to make sure we know where all the right resources are, and how much they need.”

That starts with evaluating each operational wing and designating it as one of the three types, then adapting its staffing to ensure it has all the elements it needs to fulfill its mission. Leaders did not give a timeline for when that process would take place.

While it’s clear some units will need additional personnel, Spain offered that the process could yield excess billets, as well. Once that is completed, manning requirements will be adjusted to ensure wings can support their new mission requirements.

By standardizing its wings, the Air Force will have a force-sizing construct that aligns with the Army’s Brigade Combat Teams, the Navy’s Carrier Strike Groups, and the Marine Corps’ Marine Expeditionary Units—a key asset in explaining to joint force leaders how deploying one or more units today will impact readiness tomorrow.

“We can articulate it more effectively and advocate for a particular method or means” in response to an emerging requirement, Spain said. The construct will also help the Air Force explain how employing a given unit for one contingency could impact other requirements in the future.

Finally, the change is meant to improve stability for Airmen who even now, under AFFORGEN, face uncertainty. Many Airmen may know they are in “a bucket” that says they could deploy, Epperson said. But “they don’t know what unit, what location, and whether or not they’ll get tapped. As we move forward, they will have that predictability, because they will go into a combat service support team [and will] know, in one year, I’m going to deploy. And they’ll know exactly what location they’re going to deploy to.”

That contributes to a better quality of life for Airmen and their families as well as a better trained and prepared force for the nation and joint-force partners.

“This is about warfighting effectiveness,” Spain said. “The next fight is not going to be the same fight as the one that we’ve executed for the past 30 years.”

USAF Embraces Warrant Officers for Cyber

Mike Tsukamoto/staff

By David Roza

Among the most talked-about news at the AFA Warfare Symposium was Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin’s announcement that the service will try bringing back warrant officers in the cyber and information technology career fields.

The move comes 44 years after the last Air Force warrant officer retired in 1980. The Air Force and Space Force are the only military services not to include warrant officers, who fill technical rather than leadership functions in the other military branches. The Air Force has long mulled whether to bring them back, said retired Chief Master Sgt. of the Air Force Gerald Murray.

“I made an off-the-cuff statement during the time I was Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force: ‘over my dead body,’” Murray said in a panel with CMSAF JoAnne Bass and Chief Master Sgt. of the Space Force John Bentivegna.

But now, Murray sees the need for warrant officers in high-demand, highly technical fields such as IT and cyber. Bass echoed that opinion. When she was asked if the Air Force needed warrant officers earlier in her tenure, she said her original answer was no, “but I do know that we need a model to be able to retain our technical experience.”

“What it gets back to is: today’s Airmen and Guardians want different pathways to serve, and we are in an organization that has got to keep some of our deep technical expertise,” she said.

Indeed, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said about 100 Airmen joined other branches in recent years so that they could become warrant officers in IT and cyber. Current career tracks often take Airmen out of their specialty for long durations: Kendall recalled meeting officers returning to cyber after three years in a completely different field.

“Now I don’t know about you, but if I had a doctor who had not been doing medicine for three years and who was about to do surgery on me, I would be a little nervous,” the Secretary said on the final day of the symposium. “We need continuity in some of these people.”

That need is more acute in the cyber and IT fields, where technology moves particularly fast, Allvin explained in his keynote address at the symposium. A document posted anonymously on the unofficial Air Force amn/nco/snco Facebook page and the Air Force subreddit directs Air University to develop a concept of operations for establishing a training pipeline at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala.

The initial cohort, according to the document, would consist of 30 prior-service personnel, but a separate planning document obtained by Air & Space Forces Magazine says the pipeline could scale up to 200 junior warrant officers and 50 senior warrant officers a year. Director of the Air National Guard Lt. Gen. Michael Loh told Air & Space Forces Magazine that his troops will be among the initial cohort.

“The folks that bring the predominant force structure from a cyber, IT perspective is the National Guard; over two-thirds of the Air Force capability resides in the National Guard,” he said.

Continuity is already a selling point in the Guard, he said, but “we need some technical expertise in the Active component that we tend to lose.”

Success may involve measuring how long warrant officers stay in the service, what level of talent they develop as warrant officers, and how much they increase productivity and effectiveness in the IT and cyber arenas. Those metrics may take years to collect, but Allvin cautioned against expanding the program too quickly.

“We’re still a force that develops leaders, so we’re not going to relegate the entire force to warrant officers,” he said. The same goes for the enlisted force, which he described as “the envy of the world and it scares the [blank] out of the adversary. We need to make sure we maintain that.”

Kendall further emphasized the need for caution before possibly expanding the program.

“I don’t know if it’ll be a year or two years or whatever, but I think at some point we’ll want to think about ‘are there other fields this will make sense in too,’” he said. “But the emphasis right now is on getting cyber and IT right.”

The Space Force is considering several changes to better recruit and retain talent, such as offering full-time/part-time status to Guardians, but top service leaders passed on introducing warrant officers.

“Because of the way we were designed, all of our enlisted personnel have very technical paths,” Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman told reporters at the symposium. “And so we feel like there’s other avenues to provide them the compensation they need.”

The Space Force already provides a model where Guardians who ‘just want to do my job,’ can keep doing that, Bentivegna explained. Plus, the service’s small size, at just 9,400 Guardians, makes having a third category of Guardian “just not feasible for us from the logistics perspective,” he added.

The reintroduction of Air Force warrant officers was one of several programs announced at the symposium that are meant to gain an edge in the competition with industry and other services for technical talent. Others include expanding technical tracks for Air Force officers, creating technical tracks for enlisted Airmen, and “tailored career categories” for “critical technical areas, notably cyber and IT,” according to an accompanying Air Force document.

Air Education and Training Command will also be expanded and renamed Airman Development Command, a move meant to better align education and training efforts across the service. To make sure those Airmen are ready for deployment, the Air Force is emphasizing a new concept called “Mission Ready Airmen,” which is meant to train Airmen to work in small groups on difficult problems under contested conditions.

“I think there’s more to come in terms of ‘how do we retain the force that we’re going to need,’” Bass said. “It’s not going to be by policies from the ’90s or the 2000s. We really do have to reimagine what that looks like.”

Meanwhile, the Space Force plans on doubling its special pays to $8.3 million for enlisted Guardians in fiscal 2024 over last year’s $4 million. Saltzman said he also wants to get Guardians out into the private sector so that they don’t feel as if they are falling behind their peers in technical knowledge.

Though many of these changes are still in the works, Airmen on social media forums were pleased to see the return of warrant officers.

“Everything we’ve discussed about warrant officers in our shop so far has been positive,” one anonymous cyber Airman told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

The corresponding pay bump would not go unnoticed. DOD’s 2024 pay scale offers $5,792 in basic pay per month to warrant officers in the W-2 grade with 10 years of service, compared to $4,886 for an E-7 with the same level of experience.

The money alone probably is not enough to entice new recruits or convince them to stay, the Airman said, but “this at least makes it less insulting/painful for folks to stay and incentivizes those who really love the military-unique things you can’t do as a civilian or contractor, much less the commercial sector.”

The cyber expert anticipated plenty of questions and messiness as the Air Force actually puts rubber to the road, “but still all-around goodness.” More details would, “I’m sure, help those folks interested in making the jump.”