Future Mars plane could help solve Red Planet methane mystery (exclusive) (Image Credit: Space.com)

Mars methane is hard to trace, but a solution might be on the way.

An early-stage airplane concept called MAGGIE will soon kick off a nine-month NASA-funded study to explore its feasibility for soaring over Mars. It won’t go to the Red Planet any time soon, if ever, but there’s a clear science need for more flying vehicles on Mars.

NASA’s Ingenuity helicopter, the first heavier-than-air vehicle to soar on Mars, finished 72 flights after arriving with the Perseverance rover in February 2021. While Ingenuity had a hard landing in January 2024 that grounded it for good, there’s plenty of room for more flying vehicles in the future.

MAGGIE — short for “Mars Aerial and Ground Intelligent Explorer” — is designed to operate for a Martian year (nearly two Earth years) anywhere around the Red Planet. Flying 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) above the surface, one of its prime missions could be finding methane. That elusive molecule could be a sign of life, but scientists have had little luck figuring out its presence in the Martian atmosphere after decades of searching.

Related: Life after Ingenuity: How scientists hope to reach the skies of Mars once more

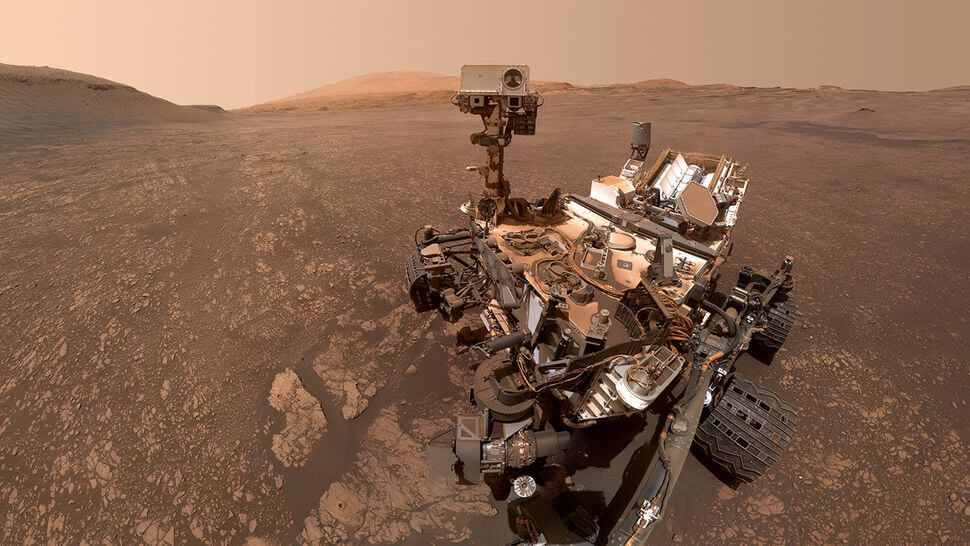

Methane, a possible biosignature gas, has been hard to find on Mars. It pops up now and again in the atmosphere, detectable by spacecraft on or orbiting the Red Planet or by powerful telescopes here on Earth. NASA’s long-running Curiosity rover mission (ancestor to Perseverance), for example, has repeatedly detected methane since 2012, but the levels go up and down — a background level of less than 0.5 parts per billion (ppb) molecules of air, sometimes spiking up to 20 ppb.

The next logical step could be a flying vehicle like MAGGIE, principal investigator Gecheng Zha told Space.com. Zha is CEO of Coflow Jet and a professor at the University of Miami who received nine months of funding under the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program to explore this concept further.

MAGGIE could stay in the air for a distance of 111 miles (179 km), its design suggests, on a single charge of its solar panels. Zha says high-resolution instruments on board could pick out trace amounts of methane in the atmosphere, or other potential transient phenomena like liquid water on Mars. Better yet, “we can also land in any place we’d like to get samples,” he told Space.com.

MAGGIE’s presumed range comes courtesy of patented technology that would use air compressors to keep the aircraft aloft. The air compressors move small amounts of atmosphere from the back of the wings toward the front, both increasing lift and reducing drag.

This process would allow MAGGIE to be flexible for different temperatures and pressures of atmosphere, allowing it to navigate the thin air of Mars during different seasons and at different latitudes, particularly during challenging seasons like winter. Normally, the Martian atmosphere’s pressure is between 6 and 10 millibars, just one one-hundredth of Earth’s surface pressure, according to NASA. And during the cold season, roughly 25% of the atmosphere condenses on the polar caps, causing a further plunge in Red Planet pressure.

Before reaching Mars, MAGGIE must meet the major goal of its NIAC phase 1 study, which is to determine if the airplane could indeed work in the thin atmosphere of Mars. “We’ll do more vehicle design and a feasibility study, and we will also do the science mission,” Zha said, emphasizing that partners such as NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California will also be involved on the science side.

Next up, if the initial MAGGIE study goes well, will be inclusion in the two-year phase 2 of NIAC to deepen the engineering and science work. A range of investigations could fly on the mission, such as examining the strange magnetic field of Mars, or photographing surface features in high definition, depending on the priority.

Zha has been working on the idea behind MAGGIE for more than 20 years, mostly on the engineering side. He received several grants before this one, too, including NASA funding for a type of jet flow control, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Award for Aviation Transports.

He was glad to see Ingenuity take flight in the interim: “When we saw the Ingenuity helicopter flying, it was very, very exciting and inspiring.” And he’s looking forward to other Martian explorers taking to the skies as soon as feasible.

That could happen relatively quickly, pending ongoing troubles with funding for NASA’s Mars Sample Return program. The current concept suggests two helicopter fetchers could ride along with the return mission in the 2030s that would bring caches back from the surface, which were collected by Perseverance.