Life after Ingenuity: How scientists hope to reach the skies of Mars once more (Image Credit: Space.com)

A swish new video has landed, animating how a robotic, 18-propellor, flying vehicle could arrive at Mars someday and begin exploring the planet from high in its pinky-red sky.

MAGGIE, the Mars Aerial and Ground Intelligent Explorer, was selected by NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program for phase 1 development in January. This means the team behind MAGGIE — hailing from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Purdue University and start-up aerospace company CoFlow Jet — will receive funding to further develop the cutting-edge technology needed to possibly make MAGGIE a reality.

The new animation depicts MAGGIE’s launch on a rocket that will take it to Mars over the course of eight months. Once there, it descends through the thin Martian atmosphere while confined within a protective heat shield; its fall is slowed by parachute. The heat shield and parachute are subsequently discarded and a retro, rocket-powered sky crane apparatus, like the ones that delivered the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers to Mars, completes the landing. Once MAGGIE has been winched to the surface by the sky crane, its 18 propellers stir into action with energy generated from solar panels that line MAGGIE’s large, winged fuselage. Rudders on the wings can direct thrust, allowing for vertical take off and landing (VTOL) — there is of course no landing strips or runaways on Mars!

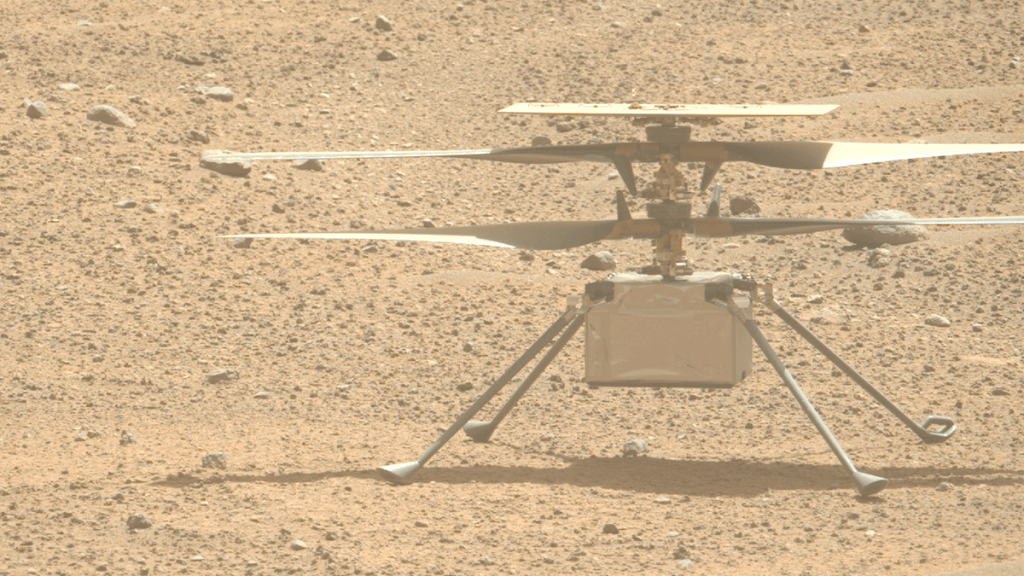

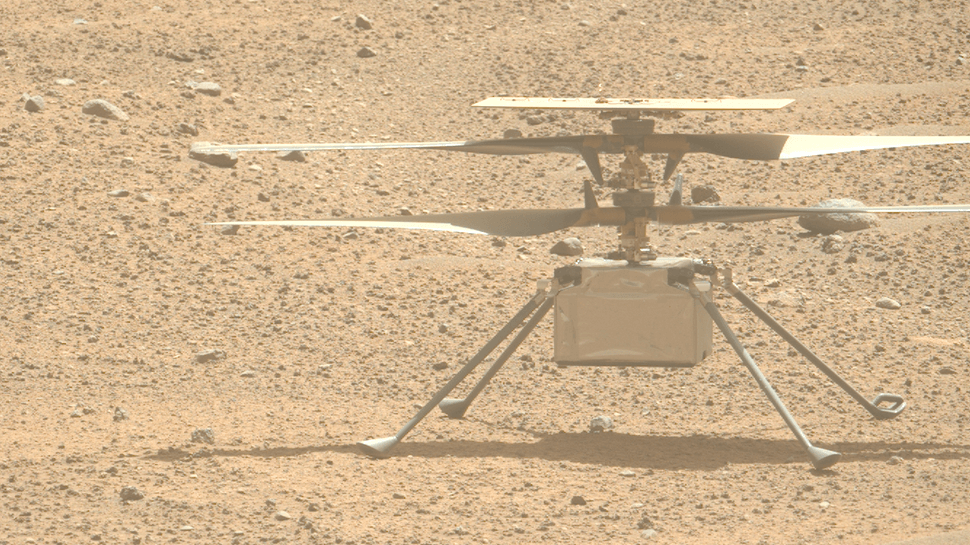

Related: NASA’s Mars helicopter Ingenuity has flown its last flight after suffering rotor damage

MAGGIE’s planned capabilities are impressive. For instance, it would be built to reach Mach 0.25 on a fully charged battery. In Mars’ fragile atmosphere, Mach 1 — the speed of sound — is slower than on Earth, and has been measured to be 879.3 kilometers per hour (546.4 miles per hour) at ground level. Therefore, Mach 0.25 at MAGGIE’s cruising altitude of 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) is about 210 kph (130 mph). MAGGIE’s time spent in the Martian sky will be limited by its solar panels that will only function during the day and require time to charge up in the morning, but MAGGIE’s total range across a Martian year (687 Earth days) would be 16,048 km (9,972 miles).

It would be able to achieve this speed thanks, in part, to CoFlow Jet’s patented technology, which features a series of air compressors built into the vehicle’s wing that suck in small amounts of air from the back of the wing, then blow it out at the front of the wing. This mechanism acts to increase lift and reduce drag. MAGGIE’s CoFlow Jets and propellers would have to work harder on Mars than on Earth because of the thinner atmosphere, which is just 6.25 millibars at surface level, compared to Earth which has a pressure of 1,013 millibars at sea level. The situation is made even worse in the winter, when the atmospheric pressure drops by 25% because the carbon dioxide freezes out onto the polar caps.

Consequently, the phase 1 study will investigate how MAGGIE could successfully operate in the thin atmosphere. MAGGIE will then be nominated for inclusion in phase 2, during which the team would be able to receive greater funding to further develop the concept and mission parameters. Those would include its science objectives such as probing Mars’ magnetism and the remnants of its internal dynamo, as well as studying the anomalous plumes of methane that could potentially be the product of biology. Of course, MAGGIE would also provide breathtaking views!

MAGGIE would have some big shoes to fill — only in January did the mighty little Ingenuity helicopter’s mission come to an end after 72 flights. The culprit was some flight-related damage inflicted to Ingenuity’s rotor blades. Meanwhile, a helicopter mission to Titan, called Dragonfly, is set to launch in 2028.

It’s also worth considering that MAGGIE isn’t the only concept that has successfully received NIAC phase 1 funding. There are a dozen projects in total, including a potential sample-return mission to Venus, a very-long baseline interferometer that would see a radio telescope sent to the far side of the solar system, and a swarm of tiny spacecraft that could one day visit and explore the nearest star system to us: Proxima Centauri and its three known planets.