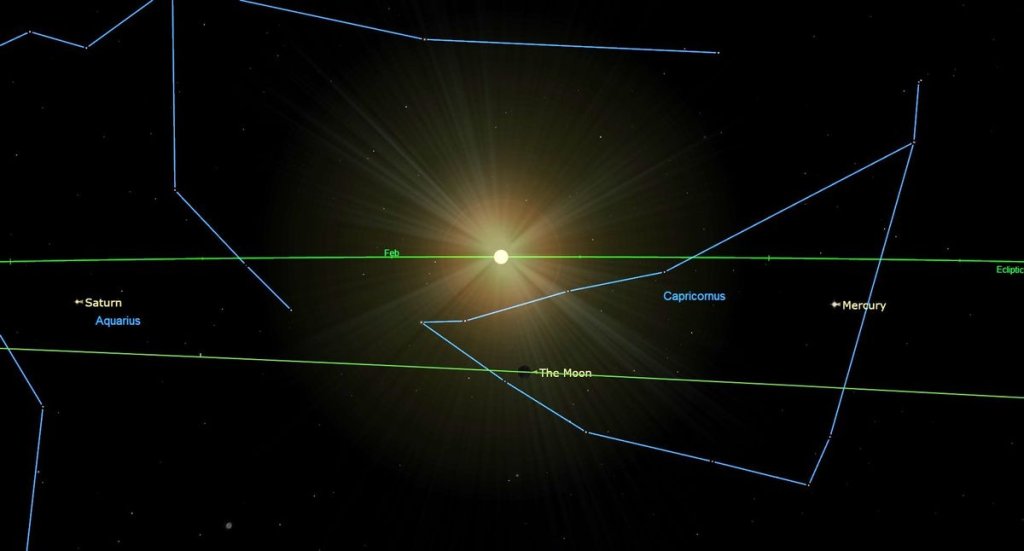

February’s ‘super’ new moon leaves the night sky nice and dark tonight (Image Credit: Space.com)

The new moon occurs Feb. 9, at 17:59 p.m. EST (2259 GMT), in New York, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory, the same day Mars, Venus and Mercury form a line of planets in the predawn hours.

When the moon is directly between the sun and Earth, we have a new moon. The two bodies share the same celestial longitude, a projection of the Earth’s own longitude lines on the celestial sphere, an alignment is also called a conjunction. New moons are invisible unless the moon passes directly in front of the sun, producing a solar eclipse (the next is on April 8). Lunar phases depend on the position of the moon relative to the Earth, so the timing is the same with the differences being a result of time zones.

February’s new moon occurs just hours before the moon reaches perigee, the closest to Earth it reaches during its orbit. During full moons, this makes the moon appear ever so slightly larger than at other times, leading to the popular term “supermoon.” While the moon will technically appear bigger during the new moon due to its proximity to Earth, it will be invisible while lost in the sun’s glare.

Related: Full moon calendar 2024: When to see the next full moon

In a number of cultures – notably Hebrew, Muslim and Chinese — new moons are the beginnings of lunar months. For example in the Hebrew the February new moon is the last day of the month of Shevat, while in the Islamic calendar it is the 28th day of Rajab; this is the day after many Muslims celebrate the nighttime journey of the prophet Muhammed to Jerusalem.

In the Chinese calendar it is the 30th day of the last month, called Làyuè (腊月), or Preserved Month, for the tradition of preserving food ahead of the Spring Festival, which is the next day on Feb. 10, the first day of Zhēngyuè (正月) or Start month, for the start of the year.

Visible Planets

Before the sun rises on Feb. 9 one can look southeastward to spot Venus; the planet rises in New York at 5:27 a.m. local time. Sunrise isn’t until 6:58 a.m. and civil twilight is at 6:29 a.m., (the time the streetlights will start turning off in many locations).

It’s relatively easy to spot Venus rising; Venus is the third-brightest object in the sky so it should be easy to spot, and one can use it to find Mars, which will be (from mid-northern latitudes) to the left and below it. Mars will be much more difficult to see because it rises at 5:53 a.m., when the sky is starting to get light. By sunrise Mars will be only about 9 degrees high.

Mercury rises last, at 6:28 a.m. and is largely lost in the solar glare as it is only 5 degrees high at sunrise, below and to the left of Mars. A note of caution: observing any objects close to the sun requires care – it is important to be careful as accidentally pointing an optical aid (such as binoculars) at the sun can cause permanent eye damage. This is true even of the light part of the sky just before sunrise.

Moving southwards, the angle the three planets make with the horizon will be steeper. In Miami, Venus rises at 5:17 a.m. local time and Mars follows at 5:43 a.m. Mercury rises at 6:21 a.m. By sunrise, which is at 7:00 a.m. all three planets are higher in the sky than in New York City – Mercury is a full two degrees higher, about 7 and a half degrees above the horizon. It will still be very difficult to see, but easier to find than at higher latitudes. If one has a flat horizon and clear conditions one can just see it as it comes up. By sunrise Mars is 15 degrees above the horizon, with Venus is nearly 20 degrees above the horizon.

Closer to the equator the trio of planets gets higher; in Quito, Venus appears to be directly above Mars, which is in turn directly above Mercury. Venus is 21 degrees above the horizon by 6 a.m.; the planet rises at 4:20 a.m. local time. Mars rises at 4:43 a.m. and Mercury rises at 5:33 a.m., nearly a full hour before sunrise at 6:25 a.m. By sunrise on Feb. 9, Venus is at an altitude of 27 degrees and Mars is at 21 degrees; Mercury reaches about 12 degrees, while Mars is 19 degrees above the horizon. Venus is This makes the innermost planet easier to find; if one has a flat horizon and clear conditions one can just see it as it comes up.

Moving into the Southern Hemisphere our line of planets starts to tilt back towards the horizon (though in the opposite direction from the Northern Hemisphere). From Santiago, Chile, Venus will appear to be above and to the left of Mars, which will be above and to the left of Mercury. Santiago is at about 33 degrees south, about as far below the equator as Charleston, South Carolina is above it. By sunrise at 7:13 a.m. on Feb. 9, Venus is at an altitude of 27 degrees and Mars is at 22 degrees; Mercury reaches about 13 degrees.

In mid-northern latitudes (as in New York) Jupiter is high in the western half of the sky the evening of Feb. 9, in the constellation Aries. By 6 p.m. it is nearly 60 degrees above the horizon, easy to see as the sky darkens (in New York, sunset is at 5:23 p.m.) The planet sets that evening at 11:54 p.m. Saturn, meanwhile, is much closer to the horizon at sunset; only 13 degrees high in the southwest; observers won’t have much chance to catch the planet before it sets at 6:45 p.m.

In Quito, Jupiter is similarly high in the sky Feb. 9; a full 67 degrees high in the west at sunset (6:31 p.m. local time). The planet will become more visible a bit later; by 7:30 p.m. it is still 55 degrees above the western horizon, and the planet sets at 11:24 p.m. Saturn, meanwhile, sets at 7:38 p.m., meaning that by the time the sky gets dark enough to see it against the sky – approximately 7 p.m. – the planet is only 8 degrees high.

From Santiago, Chile (cities such as Cape Town and Sydney, Australia, are near this latitude as well) where the sun sets late, at 8:40 p.m. (it is summer in the Southern Hemisphere) Jupiter is lower than in the Northern Hemisphere, only 35 degrees high in the northwest at sunset; it sets at 12:16 a.m. Feb. 10. Saturn is only 10 degrees high at sunset; it sets at 9:34 p.m. local time. By the time the sky gets dark the planet is almost too close to the horizon to readily observe.

Constellations

By about 7 p.m. the Big Dipper will be rising in the northeast, with the “bowl” facing north (to the left), and the “handle” pointing towards the horizon. The two stars at one end of the Dipper are Alpha and Beta Ursae Majoris, also called Dubhe and Merak. Dubhe is not only the brightest star in Ursa Major but the name “Dubhe” is an Arabic word for “bear.” The two stars point to Polaris, the North Star. Using those same “pointers” one can go in the opposite direction, and find Leo, the Lion, which will be rising above the due eastern horizon. The two stars at the back of the Dipper’s bowl point to the star Regulus, the brightest star in Leo.

Turning southwards in mid-northern latitudes one will see Canis Major, Orion and Taurus. Orion’s famous belt is visible even from city locations, as is Sirius, the “Dog Star” in Canis Major. Going towards the zenith from the north, one will see Auriga, the charioteer, and Perseus, the legendary Greek hero. By 9 p.m. Sirius is almost due south – the star transits, or crosses the meridian, roughly between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m. local time (this depends on how close to the eastern or western edge of the time zone boundary one is at).

As Sirius reaches its highest point one can see a large six-sided asterism called the Winter Hexagon. It’s a shape formed by Capella (the northernmost and highest of the group), and moving clockwise, Aldebaran, Rigel, Sirius, Procyon, and Pollux. Procyon is a bright white star that is Alpha Canis Minoris, the alpha star of the Little Dog, and is one of our closer stellar neighbors at 11.5 light years away; in the Northern Hemisphere skies the only bright star that is closer is Sirius, at 8.6 light years distance.

As the night progresses observers can watch Virgo rise by about midnight. The Big Dipper can help here; using the handle one can “arc to Arcturus” by drawing a sweeping arc to Arcturus, an orange-yellow star in Boötes, the Herdsman, and then keep going to reach Spica, the brightest star in Virgo. The Dipper will be high in the northeast, with the bowl facing down and to the left.

In the Southern Hemisphere, it is fully dark by about 9:30 p.m., and the Southern Cross is rising in the southeast. There is no equivalent of Polaris in the southern skies; one can use Crux, the Southern Cross, to point in the direction of the Southern Celestial Pole, but the constellations in that region such as Chamaeleon and Octans (the Octant) are made up of fainter stars (and none are on the South Celestial Pole).

To find the pole, a good method is to draw an imaginary line through the center of Crux (along what would be the vertical part of the cross) and keep going until you hit another bright star, called Achernar, which will be on the opposite side and about the same distance from the Pole as the Cross. The South Celestial Pole is about halfway between them. Just below Crux is the constellation of Centaurus the Centaur, containing Alpha Centauri, our nearest stellar neighbor; to the left of Alpha Centauri is Hadar, the second-brightest star in the Centaur.

Looking upwards I the southeast — following the Milky Way, if one is in a dark sky site — one encounters the three constellations that make up Argo, the legendary ship that carried Jason and the Argonauts: Puppis the deck, Vela the sail, and Carina the keel. Even if one can’t see the Milky Way because of city lights, the “clustering” of relatively bright stars in the region is noticeable. Vela, the sail, is a rough circle of eight medium-bright stars. To the right of Vela is Carina, whose brightest star is Canopus, one of the most luminous stars in the solar neighborhood. It is 310 light years away and magnitude -0.76, making it some 10,000 times as bright as the sun, according to observations by the European Southern Observatory.