High-energy ‘sun goddess’ particle opens possibilities for new physics, exciting scientists (Image Credit: Space.com)

Over the years, scientists have managed to unveil the existence of quite a view intriguing particles, pushing the entire field of physics forward with each discovery. There’s the “God Particle” for instance, aka the Higgs Boson that grants all other particles their masses. There’s also the so-called “Oh My God!” particle, an unimaginably energetic cosmic ray.

But now we have a new particle in town. It’s named the “sun goddess” particle — and is fittingly extraordinary.

This particle has an energy level one million times greater than what can be generated in even humanity’s most powerful particle accelerators; it appears to have fallen to Earth in a shower of other, less energetic particles. Like the “Oh My God!” particle, these bits come from faraway regions of space and are known as cosmic rays. The particle has been dubbed “Amaterasu” after Amaterasu Ōmikami, the goddess of the sun and the universe in Japanese mythology, whose name means “shining in heaven.”

And just as its mythological namesake is shrouded in mystery, so too is the Amaterasu particle. Its discoverers, including Osaka Metropolitan University researcher Toshihiro Fujii, don’t know where the particle came from or indeed what it is. They also still aren’t sure what kind of violent and powerful process could have given rise to something as energetic as Amaterasu.

“This is the most energetic charged particle ever detected by the Telescope Array experiment,” Fujii told Space.com.

The hope is that, just as Amaterasu is credited with the creation of Japan according to the Shinto tradition, the Amaterasu particle can help create an entirely new branch of high-energy astrophysics.

Related: High-energy cosmic rays may originate within the Milky Way galaxy

The “Oh My Goddess!” particle

High-energy cosmic rays are extremely rare to begin with, but Fujii said the Amaterasu particle has an energy level not seen in a staggering 30 years of cosmic ray detections.

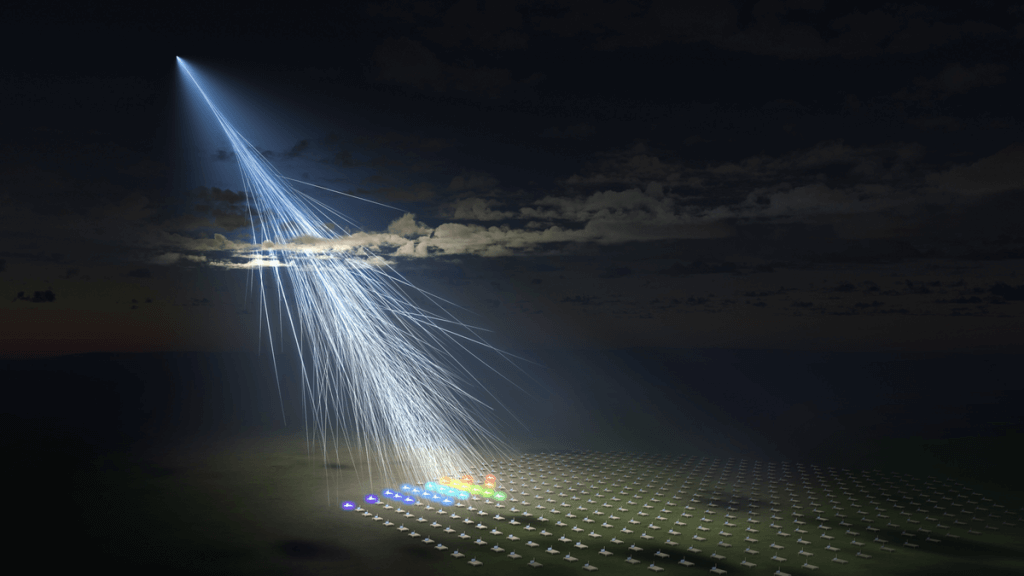

In fact, when the researchers spotted Amaterasu with the Telescope Array experiment — involving 507 detectors spread across 270 square miles (699 square kilometers) of the high desert of Millard County, Utah —they initially thought the detection must be some kind of mistake.

“I thought it would be my mistake or bug, and then after checking the details of the event, I was excited to find it was not an error,” Fujii said.

First spotted by the Telescope Array experiment on May 27, 2021, the Amaterasu particle exhibits an energy of 224 exa-electron volts (EeV). For contest, one EeV is equivalent to 10¹⁸ electron volts. This puts Amaterasu on a similar energy level to the most energetic cosmic ray ever discovered — yes, that’s the “Oh My God!” particle, which was detected in Oct. 1991 by the Fly’s Eye camera in Dugway Proving Ground, Utah. The latter had an energy of 320 EeV.

“The Amaterasu particle should be an important messenger from the universe about extremely energetic phenomena, but we need to disentangle the origin of this mysterious particle,” Fujii explained.

There isn’t an astrophysical object, or any cosmic event for that matter, in the direction from which the sun goddess particle appears to have come from. That’s why scientists are pretty unclear on what led to its creation. But, while the origins of the Amaterasu particle may be currently unknown, Fujii does have some avenues of investigation to follow up on. Importantly, some of these ideas could extend beyond the Standard Model of particle physics, which is the best outline we have of the universe’s particle zoo and how each of those particles interact with one another.

“One possibility is the particle has been accelerated by extremely energetic phenomena, such as a gamma-ray burst or a jet from a feeding supermassive black hole at the center of active galactic nuclei,” Fujii said. “Another possibility is creation in an exotic scenario such as the decay of super heavy dark matter — a new particle, from unknown physics beyond the Standard Model.”

The team has been hunting cosmic rays with the Telescope Array experiment in Utah since 2008, and will now continue to do so with a fourfold improved sensitivity of the newly upgraded project. They also expect other next-generation observatories to get in on the cosmic-ray action to help scientists embark on a more detailed investigation of the Amaterasu particle.

“I am personally excited to have found a new mystery in science to solve,” Fujii concluded.

The team’s research will be published on Nov. 24 in the journal Science.