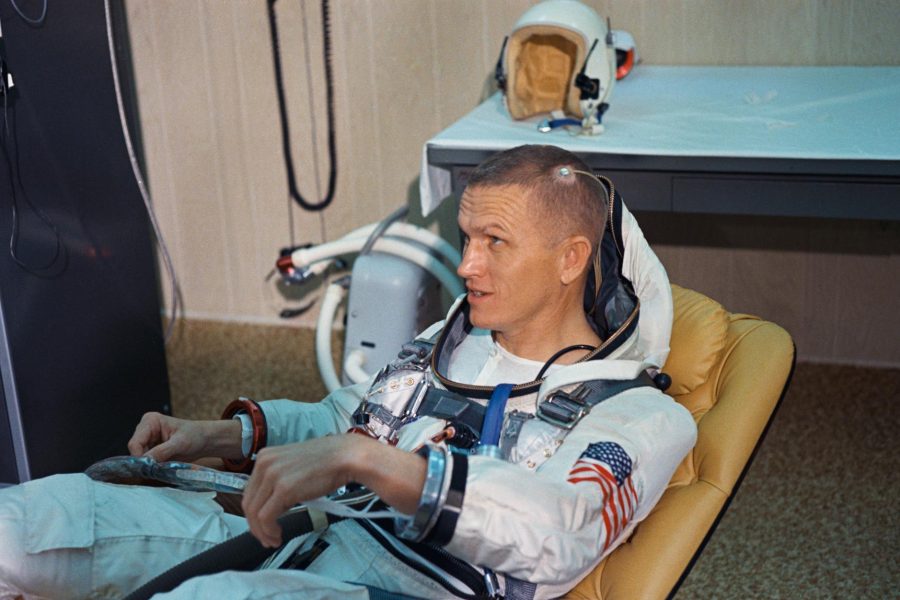

Frank Borman, Apollo 8 Commander and USAF Pilot, Dies at 95 (Image Credit: airandspaceforces)

Frank Borman, Air Force fighter and test pilot, American astronaut who commanded Gemini 7 and Apollo 8, and later head of Eastern Air Lines, died Nov. 7 at 95.

The Apollo 8 mission, in December, 1968, was the first manned mission to fly the Saturn V rocket, and marked first time human beings traveled to and orbited the moon. The successful flight paved the way for the six moon landings by the U.S. that followed.

Borman learned to fly at 15, graduated West Point near the top of his class in 1950, and joined the Air Force, where he became an instructor and fighter pilot. He flew F-80s, T-33s and F-84s. After earning a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering at the California Institute of Technology in 1957, he taught thermal dynamics and fluid dynamics at West Point for three years. He then attended the Air Force’s test pilot school and was involved in testing a number of new aircraft, including the F-104 in a series of “zoom” to high-altitude test flights.

In 1962, Borman was picked for the second group of astronauts, and went into rotation for the Gemini and Apollo flights.

He was chosen to command his first space mission, Gemini 7, flown in 1965. The 14-day mission in the cramped capsule with fellow astronaut Jim Lovell proved that human beings could function in weightlessness for the duration needed in the upcoming Apollo flights. In addition, the craft rendezvoused with Gemini 6, validating procedures needed for future space rendezvous and docking activities.

The crew of Apollo 1—Gus Grissom, Edward White ,and Roger Chaffee—died in a capsule fire while performing a launchpad “plugs out” check of their spacecraft in January, 1967. Pressurization and the hatch’s design had made it impossible for the crew to escape. Borman was tapped to be the sole astronaut on the review board to determine the root causes of the fire.

He was also credited with persuading Congress to resume support for the Apollo program in testimony on the review’s findings. Borman expressed his confidence in the enterprise and its leadership and said the fire was due to a “failure of imagination” to anticipate every potential problem, and asked for Congress’ confidence that NASA would learn from the tragedy.

Borman was then chosen to work with North American Aviation to correct the deficiencies and defects in the Apollo spacecraft, and redesign the hatch so that future crews could escape quickly if necessary.

Picked to command Apollo 8, Borman accepted the challenge when the 1968 mission was changed. It was originally intended to be a deep-space test of the Apollo Command and service modules with the lunar module. But the Soviet Union had achieved a lunar circumnavigation with a “Zond” unmanned craft earlier in the year, and intelligence indicated Russia might try to declare victory in the moon race by sending two cosmonauts on a similar flight in a Soyuz craft before the end of the year.

Viewing the situation as virtually a military battle, Borman took on the retooled mission, which only allowed a few months of training.

Apollo 8, which made ten lunar orbits, came off with virtually no technical glitches. It confirmed the navigation techniques and computer software needed to go to the moon.

It was during the mission—flown by Borman, Lovell and William Anders—that the famous “Earthrise” photo was taken of the small and fragile-looking Earth emerging over the lunar horizon, providing inspiration for the environmental movement and the creation of a national “Earth Day” less than two years later. The flight was also memorable for the crew’s reading from the biblical book of Genesis during a live broadcast from the spacecraft on Christmas Eve.

A year of traumatic events, 1968 had seen the Tet offensive in Vietnam, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, Russia’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, race riots in U.S. cities and unrest on college campuses. NASA received a telegram after the moon mission, addressed to Borman and the crew, expressing appreciation that “you saved 1968.”

Borman was NASA’s liaison with the White House for Apollo 11 in 1969, and he successfully coached President Richard Nixon to shorten his congratulatory message to the moon landing crew and a playing of the National Anthem, as it would consume precious extra minutes of the crew’s air.

Though offered command of a moon landing mission, Borman declined, saying he had no interest in lunar exploration and that he had simply viewed the moon race as a necessary military contest with the Soviet Union that the U.S. had to win.

He told an interviewer in 1999 that “as far as I was concerned, when Apollo 11 was over, the mission was over,” and the science obtained on the five subsequent landings was “frosting on the cake.”

After leaving NASA, Borman undertook a mission for Nixon, visiting 25 countries in 25 days as a special presidential envoy, seeking help from countries to pressure North Vietnam to release American prisoners of war. Borman returned with good wishes but no practical results. He was invited to address a joint meeting of Congress to discuss the effort, in which he described the hardships of the captives, and urged lawmakers “not to forsake your countrymen who have given so much for you.”

He retired from the Air Force in 1970 as a colonel.

Later that year, Borman joined Eastern Air Lines, becoming its senior vice president for operations. He rapidly rose through the executive ranks and became chief executive officer in 1975 and chairman of the board in 1976.

Borman’s hands-on approach was on display when Eastern Flight 401 crashed in the Florida Everglades in 1972. Borman took a helicopter to within 150 yards of the crash site, and, wading through deep water, helped locate survivors and get them to rescuers.

At first, Borman’s management turned the ailing airline’s fortunes around, slashing the ranks of middle management as well as corporate perks, and persuading workers to accept a pay freeze. By the late 1970s, Eastern was again profitable, and some workers received higher pay through a kind of profit sharing plan.

Borman then bought a fleet of more fuel-efficient aircraft to cope with rising gas prices, but soon after, airline deregulation—with some startups charging less than their costs to rapidly gain market share—combined with Eastern’s debt, clobbered the airline’s bottom line. Wage growth, already anemic, evaporated, and unions agreed to new contracts on the condition that Borman resign, which he did in 1986, although he stayed on the payroll as a consultant for a number of years. He served as CEO of Patlex Corp. a small technology company, from 1988.

After Eastern, Borman operated an auto dealership with his son, and then became a cattle rancher in Montana. In 1996, with co-writer Robert J. Serling, he published his autobiography, Countdown.

In retirement, he served on a number of corporate boards, including Home Depot and National Geographic.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said Borman “knew the power exploration held in uniting humanity when he said, “Exploration is really the essence of the human spirit.’ His service to NASA and our nation will undoubtedly fuel the Artemis Generation to reach new cosmic shores.”

Borman’s lengthy list of awards included the Harmon Trophy—twice, for Gemini 7 and Apollo 8—and the Collier Trophy for the Apollo 8 mission, along with Lovell and Anders; the U.S. Air Force Space Trophy; the Robert H. Goddard Memorial Trophy; the Congressional Space Medal of Honor and the Society of Experimental Test Pilots James H. Doolittle Award, as well as honorary doctorates from eight institutes of higher learning, including Air University.