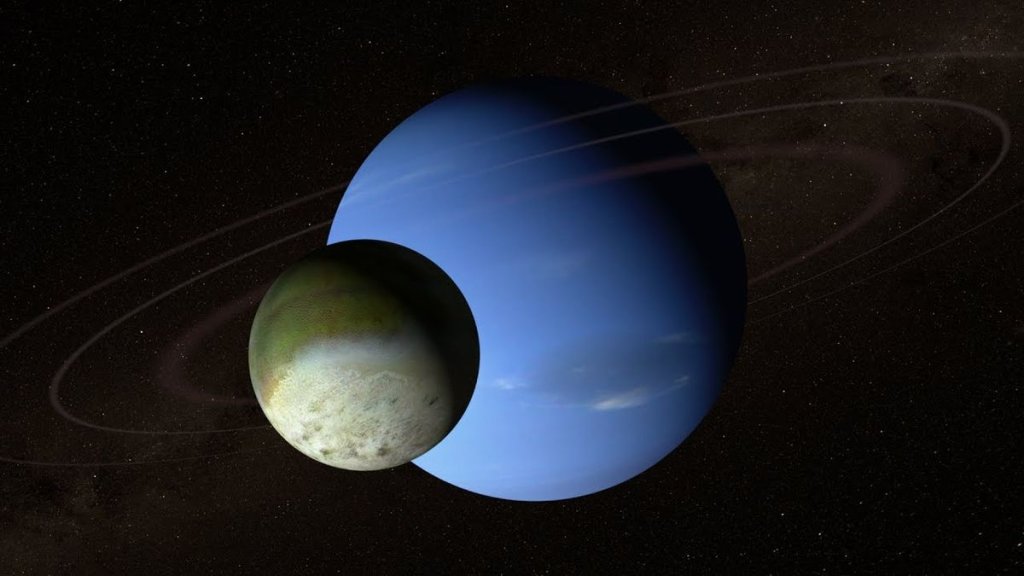

Could Neptune’s largest moon swing a spacecraft into the planet’s orbit? (Image Credit: Space.com)

The only spacecraft to visit Neptune was the Voyager 2 probe, which spent just a few precious minutes in the vicinity of this mysterious world during its historic flyby tour of the outer solar system in the 1980s. It’s been over 40 years since that mission launched. And while space agencies around the world have developed dozens of probes, landers and rovers in the decades since, none have visited the solar system’s outermost planet, let alone orbit it.

Planetary scientists have long been interested in a return visit to Neptune, but the planet is so distant that an orbiter or lander mission is next to impossible. While the New Horizons spacecraft has visited the dwarf planet Pluto, that was a brief fly-by mission. So far, the most distant orbiter that we’ve sent has been to Saturn.

Neptune is so far away that it’s difficult to fathom: It sits roughly 30 times farther from the sun than Earth does. To put that into context, Jupiter is only five times farther from the sun than Earth is. It takes years for an orbiter to reach Jupiter, and Neptune is five times farther away. While Voyager 2 took 12 years to fly past Neptune, it zoomed by without stopping, quite a very different mission profile. New Horizons flew past Neptune and its moon Triton in 2014 from a distance of about 2.45 billion miles (3.96 billion kilometers), but also just zoomed past the planet. Placing a spacecraft in orbit around the planet is quite a different matter, and remains infeasible with current technologies.

Related: Neptune is cooling down, and scientists don’t know why

One problem with a return mission to Neptune is that a flyby focused solely on that world does not provide significant bang for the buck. Without the lucky alignment available to missions in the 1970s and ’80s, we’d have to spend even more fuel to send a probe in that direction, and we wouldn’t get that much more science than we did decades ago.

The next logical step after a successful flyby mission is an orbiter, but the extreme distance to Neptune poses significant challenges. We have no clear way to haul a large enough orbiter to the Neptune system, pack enough fuel to allow it to slow down and do it all in a reasonably short amount of time.

However, researchers have shared a radical new idea for how to overcome these challenges: Use the thin atmosphere of Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, to capture a spacecraft.

In a paper appearing in the preprint database arXiv, the researchers pointed out that in 2022, NASA successfully completed the Low-Earth Orbit Flight Test of an Inflatable Decelerator (LOFTID). The goal of that program was to develop an inflatable shield to protect a spacecraft as it descended through Earth’s atmosphere and slow the craft so it didn’t crash upon landing.

The researchers proposed to aim a future Neptune orbiter at Triton and use a LOFTID-like apparatus, known as an aeroshell, to slow the spacecraft. They found that the atmosphere of Triton, despite having less than 1/70,000 the air pressure of Earth’s atmosphere, could sufficiently slow a spacecraft and allow it to enter into a captured orbit around Neptune. Additionally, they could change the angle of the aeroshell to tweak the orbiter’s alignment and fine-tune the course to get it into the perfect orbit.

To get it right, the orbiter would have to get as low as 6 miles (10 kilometers) above the surface of Triton. That’s not much higher than a typical intercontinental flight, but because Triton doesn’t have any seriously large mountain ranges (the tallest known peaks are barely a kilometer tall), there’s very little risk of a catastrophic collision with the surface.

Similar ideas have been proposed for using an aeroshell to insert an orbiter around Saturn using its moon Titan, but Titan has a much thicker atmosphere, making the job a lot easier. Although Triton’s atmosphere is incredibly thin, the moon sits relatively far away from Neptune, meaning the spacecraft would not be traveling as quickly, and would not have to reduce its speed as much, to be captured.

The researchers estimate that, using this aeroshell technique, a mission to Neptune could take as little as 15 years, which is far shorter than any other current mission ideas would allow. With current approaches, an orbiter would need to pack so much fuel for use in slowing itself down at Neptune that it would never be able to reach a high velocity, making the trip extremely long.

And there’s a bonus to the plan: It would give us an up-close view of Triton, which is one of the strangest objects in the solar system and likely a captured Kuiper Belt object. We’d get to see this odd world from a vantage point of only a few kilometers above the ground, thus delivering some great extra science.