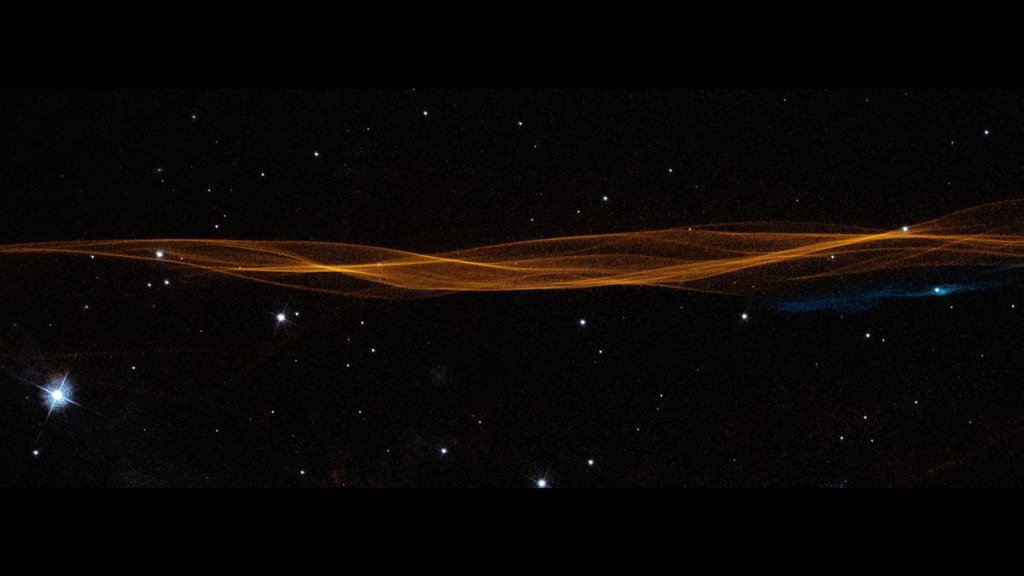

Time-lapse video shows a supernova’s aftermath ballooning into space (Image Credit: Space.com)

It is a remarkable age that we live in — a time when astronomers have the ability to capture direct footage of space explosions that happened long before you and I existed. Such is the case for a cosmic time-lapse video scientists released on Thursday (Sept. 28).

Constructed from about 20 years of Hubble Space Telescope data, the video zooms-in on the bubbling remnants of a supernova, or explosive star death, that happened a staggering 20,000 years or so ago. In particular, the time-lapse focuses on a small sliver of what’s known as the Cygnus Loop, a nebula that represents the entirety of one stellar detonation’s aftermath.

Nebulas like this one are giant clouds of dust and gas in space, built from the guts of a star that once dramatically died in a supernova eruption. Because they contain all that old star matter, some of these space clouds are known to turn into key components of our universe called “stellar nurseries.” As the name suggests, that’s where old star parts can come together to form new stars.

Related: Hubble Space Telescope discovers 11-billion-year-old galaxy hidden in a quasar’s glare

Returning to the Cygnus Loop, however, this nebula was first discovered in 1784, but proved to be so spectacular that scientists have continued to gaze into it ever since.

And over time, they’ve managed to glean some intriguing information from the marvel, such as the fact that it looks kind of like a 120-light-year-wide cotton ball with a bright blobby center and glowing cobweb shell. If you could see the Cygnus Loop from Earth with the unaided eye, according to a Hubble press release on the new time-lapse, it would have a diameter equivalent to six full moons sitting right next to one another.

But, as always, there was more left to learn. And the team’s new time-lapse of a Cygnus Loop slice has yielded some striking details.

What does this footage show us?

“Hubble is the only way that we can actually watch what’s happening at the edge of the bubble with such clarity,” Ravi Sankrit, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, said in a statement.

For one, as Sankrit explains, the team was able to notice density differences in the shock wave associated with the supernova as it propagates through space. As for what a shock wave is, exactly? Well, basically, when a star explodes, not only does it release an enormous amount of material, but that material is also shot out with an immense amount of force. At risk of simplification, this results in titanic waves of energy that can propagate across breathtaking distances as they heat the area surrounding the exploded star vicinity to breathtaking temperatures — and continuously push the stellar material outward at breathtaking speeds.

And that material also tends to take the shape of threads, or filaments. With regard to the Cygnus Loop’s filaments, the team says the section they looked at with the time-lapse data holds what are known as gossamer filaments, which resemble “wrinkles in a bedsheet stretched across two light-years.”

“You’re seeing ripples in the sheet that is being seen edge-on, so it looks like twisted ribbons of light,” William Blair of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, said in the statement. “Those wiggles arise as the shock wave encounters more or less dense material in the interstellar medium.”

“When we pointed Hubble at the Cygnus Loop we knew that this was the leading edge of a shock front, which we wanted to study,” Blair continued. “When we got the initial picture and saw this incredible, delicate ribbon of light, well, that was a bonus. We didn’t know it was going to resolve that kind of structure.”

But maybe most fascinatingly, it would appear that none of those filaments have slowed down at all or changed shape over the past 20 years thanks to the Loop’s shock wave. To put the speed of these waves into perspective, the Loop’s wave is forcing filaments to zoom into interstellar space fast enough that we’d travel from Earth to the moon in less than half an hour if we could match the velocity.

Yet, the team says, this is on the slow end.