Building US Space Force’s Counterspace Capabilities

Building US Space Force’s Counterspace Capabilities (Image Credit: airandspaceforces)

The U.S. Space Force must have a robust suite of defensive and offensive capabilities to credibly deter adversaries.

Americans have possessed unrivaled advantage in the space domain for a generation, but now, that advantage is at risk. Not only are potential adversaries developing their own space-based communications and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities, they are also actively working on ways to defeat U.S. space assets. China’s counterspace capabilities are the most advanced and present the largest threat, but Russia also has demonstrated intent to deny its adversaries access to commercial and international space systems. Both share the same aim: to nullify U.S. military advantages in space.

Operation Desert Storm, now more than 30 years in the past, made clear to China and other potential adversaries how critical the space domain is to the U.S. military. China sees attacking space systems as essential to prevail in a conflict with the United States and is actively fielding the most extensive collection of counterspace threats of any nation. To counter Chinese aggression in space, the U.S. must build a credible, effective Space Force with the right capabilities and force capacity.

Charles Galbreath is a Senior Resident Fellow for Space Studies at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

Download the entire report at

The enormous responsibility to protect expanding U.S. interests in space, deter aggression in space, and create effects from space that are crucial to the success of all U.S. military operations now falls on the youngest, smallest, and least-funded military service. The Space Force must be prepared and armed with sufficient resources and clear governing policies to conduct credible and decisive defensive and offensive counterspace operations.

Changes to perceived threats and vital interests have historically shaped U.S. policies on space weapons. For example, the United States pursued the development of weapons in space to defend against Soviet nuclear ballistic missile attacks as part of the Strategic Defense Initiative, also known as the “Star Wars” program. Then, from the end of the Cold War until recently, the U.S. government believed there were few serious threats requiring it to pursue space defenses. As a result, the Department of Defense (DOD) canceled its Cold War-era space weapons programs.

The “Space Commission” voiced significant concern on this issue in early 2001. Their report cited threats posed by China to U.S. space systems and called for new policies and space capabilities to defend U.S. assets in orbit. But in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and DOD’s subsequent focus on counterterrorism operations,U.S. freedom of action in space did not get the attention it needed. Discussions on whether the U.S. should develop space weapons were all but taboo, as many U.S. national security professionals continued to believe they were too futuristic, too costly, or too bellicose for a still relatively permissive domain.

While some continue to shun the topic of space weapons, the fact is there are remarkably few explicit limitations on their development. The “Outer Space Treaty of 1967” prohibits placing nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies. While there are conventions related to liability of actions, there are no formal internationally recognized agreements prohibiting the development and fielding of space weapons. Furthermore, since international law originates from a combination of international conventions, general principles of law, and international custom or practice, Russia‘s and China’s placement of weapons in orbit and their fielding of direct-ascent kinetic interceptors are, in fact, laying the legal framework to normalize space weapons.

Our decades-long view of space as a sanctuary profoundly impacted the development of U.S. systems and associated operations, leaving them ill-suited to today’s reality, where space is a warfighting domain. The U.S. military’s space architectures developed around small numbers of highly capable, very expensive satellites without on-board defenses and ground systems, because man-made threats were believed to be negligible. Now those satellites are “big, fat, juicy targets,” lacking even the maneuverability to avoid threats.

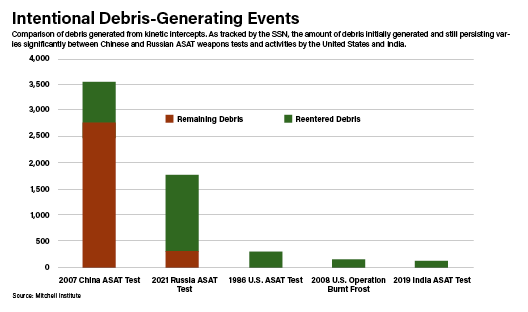

Adversaries can also exploit lengthy delays between observations and existing regional gaps in U.S. space sensor coverage to conduct counterspace operations. Growing congestion in space, as more countries became spacefaring, and as irresponsible anti-satellite (ASAT) tests by Russia and China created long-lived debris, has stretched the limited capacity of the space surveillance network (SSN). That means fewer and less frequent observations per object and increasing opportunities for adversaries to exploit the limitations of the legacy SSN.

Similarly, it became standard practice for satellites in predictable orbits to go long periods between contacts as long as they were conducting routine operations. Longer “no contact” periods, however, increased the windows of opportunity for adversaries to attack and degrade satellite capabilities.

China’s Growing Threat

According to the Director of National Intelligence’s most recent intelligence estimate, “China is steadily progressing toward becoming a world-class space leader, with the intent to match or surpass the United States by 2045.” While that may seem like the distant future, it is only 22 years away—the same amount of time that has elapsed since the 9/11 attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center. China accelerated its efforts to compete with the United States during that span, developing its own capabilities and fielding multiple offensive weapons to target U.S. and allied satellites. Notably, China does not distinguish between its military and civil space programs. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has purview over planning and direction for all Chinese space activities, even the scientific missions, meaning that any growth in China’s space programs is effectively an expansion of its military space capability.

According to the Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), China believes space deterrence is achieved through forceful persuasion.“Space deterrence signifies having powerful space forces as backing and threatening to use or actually using limited space forces to awe and contain the opponent’s military activities,” notes Air University’s CASI in its “Lectures on the Science of Space Operations.” China would employ four escalatory stages to achieve its “space deterrence” objectives:

- The first stage is a “show of space strength,” which is seen as a means of deterring would-be adversaries from taking aggressive actions, in space or on Earth.

- Next, as a potential crisis escalates, China would demonstrate its prowess through “space military exercises.” This is consistent with Chinese activities in other domains, such as a 2023 PLA naval exercise encircling Taiwan.

- China’s third stage is to change the disposition of its space forces by launching additional space assets or repositioning its existing space capabilities. China considers this a medium-high deterrence action, with the added benefit of creating a favorable space posture if the situation escalates to combat.

- Last, China would launch an “over-awing space strike” that could potentially simultaneously attack multiple U.S. space systems using a variety of weapons—what the Space Commission warned as a “Space Pearl Harbor.”

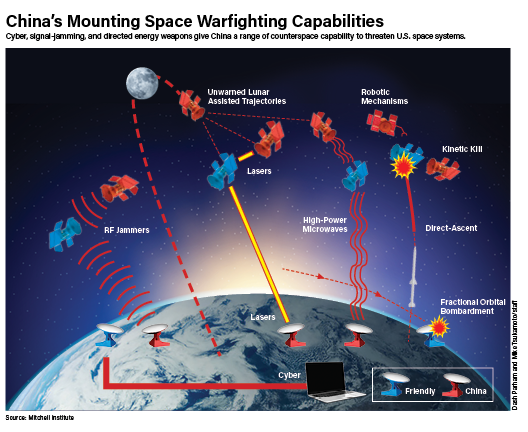

China has the most rapidly developing ASAT and counterspace capabilities of any nation, according to a 2020 report, “China’s Space and Counterspace Capabilities and Activities,” prepared for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. China has already fielded an array of counterspace weaponry, including cyber, ground-based electronic warfare capabilities, lasers, and ground-launched missiles carrying ASAT kinetic kill vehicles (KE-ASATs). The PLA has demonstrated that its KE-ASAT weapons can threaten U.S. space systems located in low Earth, medium Earth, and geosynchronous orbits. It also has operational units using radio-frequency jamming to disrupt satellite communications, navigation, missile warning, and other vital space capabilities. Additionally, the PLA fielded ground-based lasers in at least two sites capable of temporarily blinding or permanently disabling satellites. In 2006, the PLA deliberately lazed a U.S. satellite, which U.S. officials characterized as a “test.” These types of tests are not limited to lasers. In 2021 Gen. David “D.T.” Thompson, the Vice Chief of Space Operations, said Russia and China now conduct laser, RF jamming, and cyberattacks against U.S. satellites “every single day.”

The PLA is also developing and testing additional space weapons. They have demonstrated satellites that can rendezvous with orbiting U.S. satellites and attack them using robotic arms or electronic warfare. Reports indicate China has a megawatt-class solid-state laser and high-powered microwave systems mountable on satellites. It also developed a miniaturized power source for 10-gigawatt microwave weapons enabling attacks on satellites from mobile ground systems. Finally, in 2021, China demonstrated a fractional orbital bombardment system (FOBS), which can launch weapons such as hypersonic glide vehicles into orbit and then de-orbit them to destroy ground targets, according to Pentagon reports.

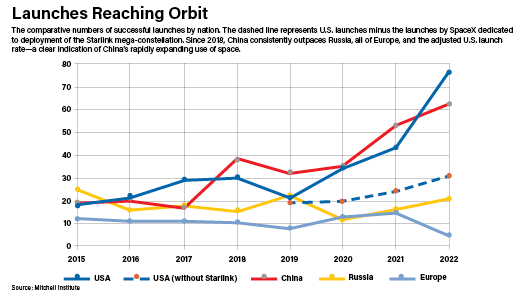

It’s not just China’s counterspace systems causing concern. China is now the second most active country in space behind the United States. From 2015 to 2022, China consistently conducted more launches per year than the United States. In 2022, China placed 45 military payloads in orbit compared to 32 payloads by the United States. These Chinese payloads include intelligence, navigation, communication, and potentially counterspace systems, all of which are now integrated into PLA military operation plans. Between 2019 and 2021 alone, China expanded its space architecture by more than 50 percent, giving it 541 operational satellites, according to the Defense Intelligence Agency.

The multitude of Chinese counterspace threats is directly in line with its escalation-based view of deterrence. China has demonstrated its willingness to resort to shows of force, and it has exercised its capabilities and ability to maneuver its space assets. The United States must now be ready for a Chinese over-awing space strike, which could launch a major conflict.

The U.S. Response

The United States is making concerted efforts to normalize global space operations to promote stability. The recent growth of the commercial and international space industries, and corresponding congestion in space, underscore the importance of adopting common standards for all spacefaring nations. As in any domain, the development of standards of responsible behavior and norms—like air traffic control procedures or international rules for navigating ships at sea—promotes safe utilization of that domain for all.

One of the most pressing norms sought by the United States is an international agreement to forgo destructive, direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tests. In early 2022, Vice President Kamala Harris announced the U.S. commitment to prohibit such tests and called on other nations to voluntarily make similar commitments. Such tests leave behind long-lived debris affecting all spacefaring nations. Unlike other domains where debris from explosions or impacts eventually settle in a relatively confined area, debris in space persists as a hazard, threatening satellites and increasing the probability of collision, while forcing launch vehicles to travel through congested regions in space.

The past four decades have provided multiple examples of accidental and intentional debris-generating events highlighting the criticality of this issue. Intentional acts rightfully garner the most attention. In 2008, the United States used an SM-3 missile to destroy a non-functioning satellite carrying a fuel tank of hazardous propellant, to eliminate the risk of the tank impacting populated areas. By carefully selecting the geometry of the engagement, the United States destroyed the fuel tank and ensured the resulting debris did not persist or pose a threat to other satellites, according to an unclassified DOD summary. This event only generated 175 pieces of debris, all of which reentered the atmosphere by late 2009. In stark contrast, China tested its KE-ASAT weapon in 2007, generating 3,536 pieces of debris, most of which remain on orbit more than 16 years later. Only 750 of these objects had reentered the atmosphere as of February 2023. The international condemnation of China’s test was nearly universal, and while China has conducted seven more direct-ascent anti-satellite tests since then, none created debris or resulted in impacts on other satellites.

The U.S. declaration that it would not conduct additional debris-generating, direct-ascent anti-satellite tests led 12 other nations to make similar pledges. The United Nations General Assembly also passed a resolution for countries to forgo debris causing direct-ascent KE-ASAT tests, with 155 nations voting in favor, nine against, and nine abstaining. Notably, China and Russia voted against the measure, and India abstained.

Competitive Endurance

Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman unveiled his Theory of Competitive Endurance at the AFA Warfare Symposium in March 2023; the theory offers a framework to guide Space Force plans to deter, and if necessary, defeat, aggression in space. Competitive Endurance is focused on ensuring U.S. access to space and preventing competition from escalating into conflict. The theory follows three core tenets: avoiding operational surprise, denying first-mover advantage, and responsible counterspace campaigning. The first two tenets continue efforts predating the Space Force to improve space domain awareness and resilience. However, the third tenet, responsible counterspace campaigning, is a new area requiring further development.

The need to understand a warfighting domain and threats in it is common practice for air, land, sea, space, and cyberspace forces. However, the space domain is unique because of the sheer vastness military forces must consider and the lack of first-person awareness. Guardians derive everything they know about the space domain from data received via sensors and satellites. In a way, Guardians are always “flying on instruments” with data that is not real-time and may even be days old due to the limited capacity of the legacy SSN and SCN. This is why improving space domain awareness is critical.

In recent years, the Space Force has increased the number and types of systems supporting the space domain awareness mission. Additional sensors around high-value space assets and key regions in space, like GEO and cislunar, will be required to address the expanding number of adversary threats. Furthermore, the Space Force must make significant improvements in how it processes data from sensors. Until a more responsive and capable processing system is online, the Space Force will have difficulty achieving the necessary level of space domain awareness to counter an adversary in space.

Second, the Space Force recognizes its architecture needs to be more resilient. The legacy space architecture is vulnerable to mounting threats, incentivizing adversaries to attack quickly in conflict in order to degrade the U.S. ability to respond. This “offense dominant” condition equates to a first-mover advantage and effectively invites, rather than deters, aggression. To deny this first-mover advantage, the Space Force must increase the resilience of its architecture, reduce the time needed to reconstitute it, and defend its critical space assets to such a degree that adversaries lack confidence in their ability to attack effectively.

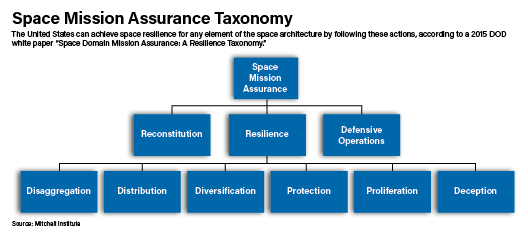

A 2015 DOD white paper, “Space Domain Mission Assurance: A Resilience Taxonomy,” suggested that resilience along with defensive operations and reconstitution comprise a larger mission assurance umbrella necessary to guarantee critical space systems will be available in a crisis or conflict to deliver essential warfighting effects.

One of the earliest and most visible realizations of this shift is in the Space Development Agency’s efforts to field a proliferated low-Earth orbit (pLEO) constellation for missile warning. By increasing the number of satellites in a constellation, this approach would make the loss of some assets tolerable, because the constellation’s overall performance could remain above an acceptable threshold. The use of small inexpensive satellites also improves deterrence by imposing greater costs on countering those satellites. When the cost of a direct-ascent KE-ASAT is greater than the target satellite, and the sheer number of satellites increases the complexity and cost of an attack, proliferation reduces the effectiveness and impact of these weapons and other co-orbital threats. The Space Development Agency’s pLEO system, coupled with existing U.S. GEO capabilities, like SBIRS, further diversifies the missile warning architecture and improves its overall level of resilience.

Additionally, diversification, distribution, and disaggregation of satellite constellations is also necessary. So is the enduring military practice of deception, which can be applied to confuse adversary understanding and complicate their ability to target U.S. satellites. Finally, the Space Force can expand its use of protection measures beyond nuclear hardening and anti-jam protection for a few satellites. By including protection measures, the Space Force can create options for decision-makers to employ defensive operations.

The booming space commercial sector and growing allied capabilities can provide critical support to both resilience and reconstitution. “Space is a team sport,” notes the Space Operations Command 2023 Strategic Plan. “We will leverage our Allies’ and Partners’ capabilities to improve the resiliency of our architecture.”

Leveraging commercial SATCOM and imagery is already common military practice. Further integration and the potential use of hosted payloads is much more extensive in the Space Force’s new approach, and while it does increase the resilience of the architecture, it also enables rapid restoration. The repositioning or use of allied or partner capability can effectively restore a lost or degraded Space Force system.

A more ambitious way to reconstitute capability is to rapidly launch new satellites. The Space Force is planning to demonstrate rapid launch for an urgent need in the VICTUS NOX mission, which aims to deliver a space domain awareness satellite into orbit within 24 hours of notification, according to Space Systems Command. While VICTUS NOX is characterized as an augmentation mission, the same approach can provide needed restoration of lost or degraded capabilities.

The final and least developed area of the Space Force’s Competitive Endurance initiative is to directly defend space systems and protect friendly forces from space-enabled attacks. Recognizing space as a warfighting domain means any serious effort to achieve space security must include space weapons. It’s oxymoronic to charge a new military service with protecting U.S. national interests in space without arming it with the weapons needed to accomplish its mission. Because it is also a key U.S. space interest to preserve the domain itself, U.S. defensive and offensive actions in space must minimize long-lived debris or other effects which might degrade friendly space architectures. This is why the Space Force calls this final element of its plan responsible counterspace campaigning.

Conclusion And Recommendations

The objective of any military force is to gain and maintain an advantage over its adversary. To achieve this, given today’s real threats in space, counterspace capabilities must be developed. The United States must have the potential to deny China access to the space capabilities that threaten U.S. space and terrestrial forces and national interests.

The Space Force should develop defensive and offensive counterspace capabilities and support elements to protect U.S. national interests in space and hold adversary space assets at risk. Concerted efforts to develop, field, and operate a range of counterspace capabilities will increase deterrence and provide the means for U.S. combatant commanders to defeat aggression should deterrence fail.

The U.S. administration, Congress, industry, and the Space Force should consider these eight steps to develop counterspace capabilities and their supporting infrastructure:

Senior U.S. civilian and military leadership should explicitly and publicly state the need to field counterspace systems. Clear guidance is essential to deter potential adversaries and align the resources necessary to field the required counterspace capabilities. Continued silence on the issue will risk further emboldening adversaries.

The Space Warfighting and Analysis Center should develop a jointly informed and accessible counterspace force design. This will require a detailed analysis of threats, current and emerging technologies, and the effectiveness and limitations of potential capabilities. Existing systems developed by the other services should also inform this force design to help prevent unnecessary duplication of effort. The force design must guide activities across the entire DOD in support of the counterspace mission.

Space Systems Command and the Space Rapid Capabilities Office should partner with industry to develop the necessary defensive and offensive capabilities. These capabilities should include both on-board and off-board defensive measures for high-value satellites. Offensive counterspace systems must be consistent with the principles of the Law of Armed Conflict and will clearly be required to defend joint and combined operations from adversary space-enabled attacks in future crises and conflicts.

The defense industry must respond quickly to USSF requirements and requests for information. Given the decades of relative neglect in the area of space weapons, the Space Force will need to be able to leverage technologies and lessons learned from industry and other domain acquisition programs in order to accelerate counterspace weapons development.

The Space Force must improve its space domain awareness capabilities to enable effective defensive and offensive counterspace operations. This includes growth in sensors and processing capabilities to enable tracking and warning of threats and a more enhanced SDA architecture capable of faster processing of collections and observations around high-value assets—and in key regions like GEO and cislunar.

The Space Force must improve its satellite Telemetry, Tracking and Command (TT&C) capabilities. This is essential to rapidly respond to threats and maintain positive control over its space weapon systems. The Space Force will need a higher-capacity TT&C architecture capable of maintaining contact with its current and future systems, including space weapons.

The Space Force must improve its testing and training architecture. Additional live, virtual, and digital elements in the National Space Test and Training Complex are required for Guardians to evaluate new counterspace systems and train all operators for the reality of space being a warfighting domain.

Congress must authorize and fund additional Space Force growth. Increases to the Space Force’s civilian and military personnel and the construction of additional facilities are needed for counterspace systems. Establishing the counterspace mission as a central task for the Space Force will create a requirement for growth beyond USSF’s originally anticipated force size of 18,000 personnel.

A war extending to or starting in space is in no one’s interest. The United States is actively pursuing means of preventing such a conflict. A strong Space Force both aids the U.S. deterrent stance and provides integral war-winning capability should deterrence fail. Norms of responsible behavior, improved resilience, and expanded space domain awareness are all vital elements of a comprehensive strategy, but by themselves will not achieve all U.S. national security objectives. The Space Force must have a robust suite of counterspace capabilities to protect national interests in space and defend fielded forces from an adversary’s space-enabled attacks.