Industry And Government Still Disagree Over Extending Suborbital Flight Safety Regulations (Image Credit: Payload)

BROOMFIELD, Colo. — The battle over what – if any – government safety regulations will be formulated for people flying on Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic suborbital vehicles and the right of those passengers to sue in the event of an accident was on full display at the Next-generation Suborbital Researchers Conference (NSRC) in Colorado this week.

On one side was the FAA, which would be able to formulate regulations as soon as the current 19-year-old moratorium on them expires on Sept. 30. Kelvin Coleman, associate administrator for FAA’s Office of Commercial Spaceflight (FAA AST), told conference attendees that the agency has sufficient data about the vehicles to begin creating rules to protect passengers and crew members.

On the other side was Karina Drees, president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation that represents the industry. Drees and others argued the companies need more time to mature their systems before the FAA steps in with regulations that could be burdensome, costly, and hinder technological progress toward safer vehicles. They want Congress to extend the moratorium, also known as the “learning period,” as it has done twice in the past.

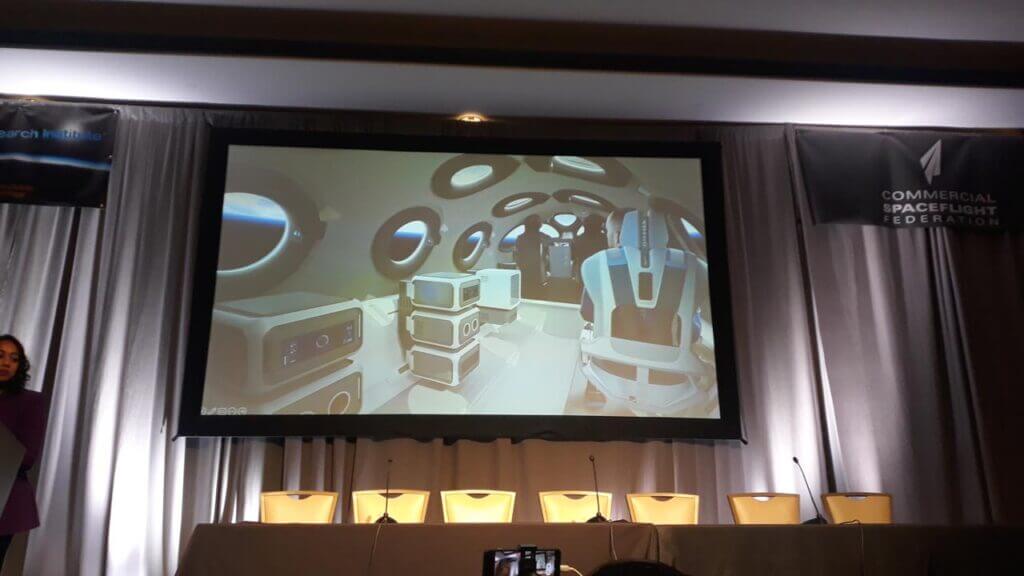

Meanwhile, employees of Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic were telling attendees that their vehicles are safe enough to carry experiments and people on suborbital flights regardless of the lack of government regulations. The prospect of being able to fly to space along with their experiments was particularly appealing for researchers in the audience.

NASA will be paying for a research flight aboard SpaceShipTwo for the Southwest Research Institute’s Alan Stern, who ran this week’s conference. Purdue University Prof. Steven Collicott, who presented at NSRC, will also conduct research on a SpaceShipTwo flight with funding from the space agency.

NASA officials said they are studying whether to take on the risk of flying its own employees on suborbital research flights. The evaluation is progressing independent of whether the FAA begins regulating the companies later this year.

At stake in the battle over regulation is who bears liability if a flight results in injuries or deaths. Passengers currently fly at their own risk under an informed consent regime. They sign waivers that acknowledge the dangers and significantly limit their ability to sue. Waivers vary from state to state, but most allow injured parties to sue only if a provider was grossly negligent or intended to cause them harm.

Colman said the increasing number of people flying on Virgin Galactic, New Shepard and SpaceX vehicles in recent years has provided sufficient data about the vehicles to begin formulating regulations. The agency wants to work with industry to develop reasonable requirements that will enhance safety, he said.

Colman said that in addition to data provided by the flights, the FAA’s Center of Excellence for Commercial Space Transportation worked with academia and industry to conduct research on safety issues. The FAA would not be regulating in a vacuum, he added.

Blue Origin has conducted six New Shepard suborbital flights with 26 on board. Passengers have ranged from an 18-year-old Dutch student to 90-year-old actor William Shatner of Star Trek fame. Blue Origin conducted 15 flight tests with no one aboard before the first crewed launch with founder Jeff Bezos and three other passengers in July 2021.

Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo has conducted four suborbital flight tests, each flown by two pilots. Two flights carried a total of five people in the passenger cabin, including company employees and Virgin Group Chairman Richard Branson. The company also conducted flights tests to lower altitudes.

The learning period was instituted in 2004 to give commercial space companies the opportunity to experiment with different approaches to spaceflight and gain flight experience before the government came in with regulations. The original eight-year moratorium was extended due to the slow progress of commercial space companies.

The FAA could step in to regulate if there was an accident or a close call. Otherwise, the agency’s oversight is currently limited to protecting the “uninvolved public.” In essence, the agency doesn’t want rockets crashing where they could injure or kill people or damage property.

Several participants predicted that Congress will bow to industry’s desire to extend the moratorium. The same thing happened to one of Colman’s predecessors nine years ago.

In early 2014, then-FAA AST head George Nield argued that the moratorium should be allowed to expire as scheduled in September 2015. He said that the term learning period implied that there hadn’t been useful lessons learned during the previous 50 plus years of human spaceflight.

Nield pointed to NASA’s long record of spaceflight from Mercury through the space shuttle program. New Shepard is a rocket and capsule system similar to Mercury-Redstone combination that Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom fly on suborbital flights in 1961. The main difference is New Shepard is fully reusable.

The U.S. Air Force also had experience with the X-15 rocket plane, which flew 199 missions with 13 reaching above the 50-mile limit the United States recognizes as the boundary of space. Like SpaceShipTwo, the X-15 was air launched from a larger airplane and glided to a landing on a runway.

Nield said that although many of the companies the FAA worked with had excellent safety cultures, there was a risk that a “bad actor” would come along to ruin it for the entire industry. If the FAA had no pass/fail criteria, he added, then everyone in the field passed regardless of the quality of their vehicles and operations.

Nield noted the FAA had been criticized in the past as having a “tombstone mentality,” in essence waiting for accidents to happen before acting to improve aviation. He wanted to be proactive, and believed that the government, industry and academia could work together to develop a set of regulations that will improve safety in advance of accidents.

Industry opposed Nield’s effort to end the learning period. It lobbied for an extension beyond 2015, arguing that it had insufficient experience in flying its vehicles for the FAA to formulate effective regulations.

Nine months after Nield’s warning, SpaceShipTwo VSS Enterprise broke up over the Mojave Desert during a flight test. Scaled Composites co-pilot Mike Alsbury died in the accident; Pete Siebold parachuted to safety with an arm broken in four places.

A National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation found that Alsbury had prematurely unlocked a mechanism that reconfigured the ship during the powered ascent phase, resulting in the vehicle breaking up. The report concluded that the probable cause of the accident was Scaled Composites’ failure to anticipate that a pilot could make such a mistake and institute safeguards to prevent it.

NTSB faulted FAA and Nield for errors in overseeing the flight test program. In 2012, the agency approved a one-year experimental permit for Scaled Composites to begin powered flight tests of SpaceShipTwo despite the company’s analysis of pilot and software error not meeting requirements. FAA AST renewed the permit in 2013 and 2014 over the objections of its own safety experts who wanted the analysis redone.

Requiring Scaled to resubmit the analysis would have delayed flight tests. Instead, FAA issued a safety waiver, signed by Nield, covering pilot and software error. Fifteen months after the waiver was issued, SpaceShipTwo was brought down by pilot error.

In the end, FAA elected not to step in with regulations after the SpaceShipTwo crash. Nield’s effort to end the learning period in 2015 came to nothing as Congress extended it.

With the moratorium once again set to expire, the same arguments are being made about whether its time for the government to step in with safety regulations.