An enormous map of the universe has been assembled from the positions of almost 1.3 million quasars; some of these quasars existed just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

By comparing this new map with what’s known as the cosmic microwave background (CMB), scientists have been able to roughly verify the distribution and density of matter in the universe, providing more clues as to how large-scale structures in the universe have evolved throughout cosmic history.

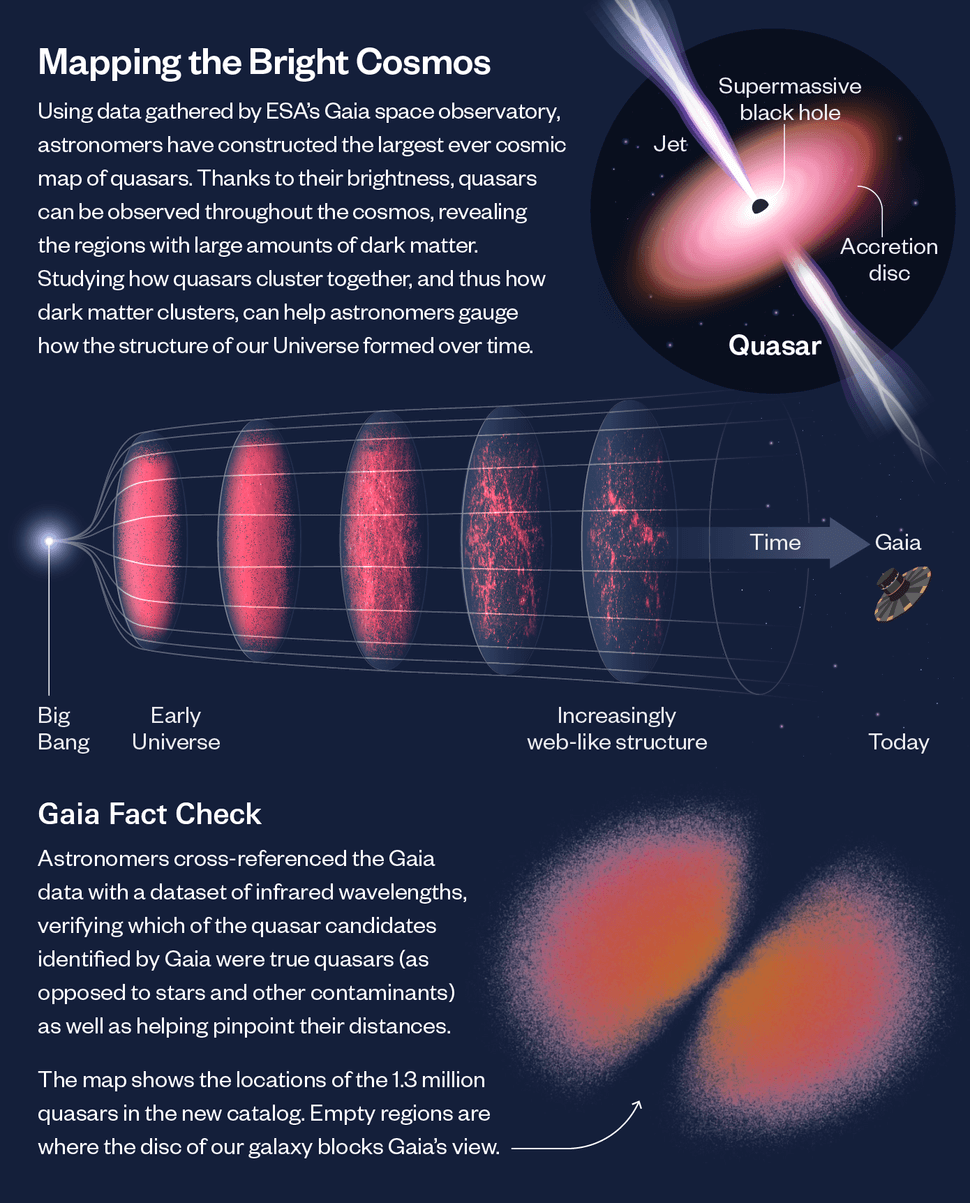

The map is based on a catalog of 1,295,502 quasar positions and redshifts, and is called “Quaia,” a portmanteau of the words “quasar” and “Gaia,” referring to the European Space Agency‘s Gaia astrometric space mission. Gaia’s principle objective is to map the positions and motions of up to a billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy — but, in the course of doing so, it also observes millions of background galaxies and quasars.

Related: Brightest quasar ever seen is powered by black hole that eats a ‘sun a day’

“We were able to make measurements of how matter clusters together in the early universe that are as precise as some of those from major international survey projects — which is quite remarkable given that we got our data as a bonus from the Milky Way-focused Gaia project,” said Kate Storey-Fisher of the Donostia International Physics Center in Spain in a statement. Storey-Fisher led the team who assembled the map, having started the project as a Ph.D. candidate while at New York University.

Quasars offer excellent guidelines for those drawing cosmological maps. A quasar is the core of an active galaxy where a supermassive black hole is greedily feeding on colossal amounts of matter. Though no light escapes the black hole itself, matter falling onto it forms an orderly queue in a spiraling accretion disk around the black hole’s maw. This disk grows so dense that friction between gaseous molecules raises temperatures in the region to millions of degrees, while magnetic fields whip up charged particles in the disk and shoot them out in the form of powerful jets. When we can see the hot disk and jet almost head on, they appear to shine brighter than anything else in the universe. This luminosity thus makes them useful yardsticks that are relatively easy to see even at huge cosmological distances.

Furthermore, quasars tend to be centered within the densest clumps of dark matter in the universe, which makes sense as it is the gravity of the surrounding dark matter halo that is drawing all that material onto the quasar for the black hole’s feeding time. As such, by mapping the most luminous objects in the universe, we’re also able to map the universe’s most mysterious material – invisible dark matter.

It’s not really that the Quaia catalog contains the most quasars ever, or even the best quality measurements, says co-author David Hogg of the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics in New York. It’s the fact that it’s showing us something new.

“This quasar catalog is different from all previous catalogs in that it gives us a three-dimensional map of the largest ever volume of the universe,” said Hogg. That volume, calibrated for the Hubble constant, which describes how the universe is expanding, is 7.67 cubic gigaparsecs (a parsec is 3.26 light years, and a gigaparsec is a billion parsecs or 25 billion cubic light years.)

The paper describing the Quaia catalog and map was published on 18th March in The Astrophysical Journal, while the pre-print of the paper comparing the Quaia map with the CMB can be found here.