This new spaceflight tech has a very retro feel.

The world’s first wooden satellite, a tiny Japanese spacecraft called LignoSat, arrived at the International Space Station (ISS) today (Nov. 5) aboard a SpaceX Dragon cargo capsule.

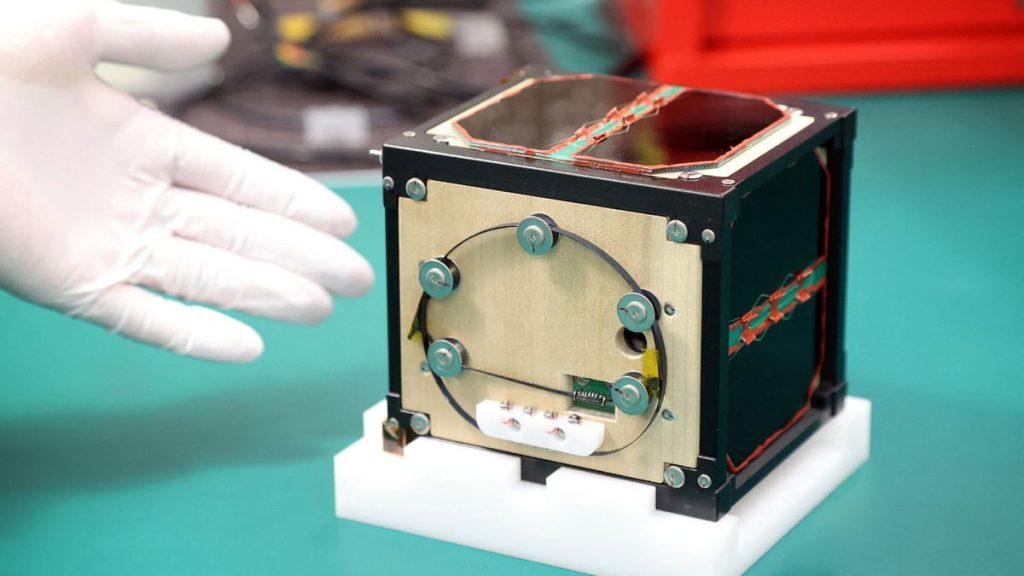

LignoSat measures just 4 inches (10 centimeters) on each side, but it could end up having a big impact on spaceflight and exploration down the road.

“While some of you might think that wood in space seems a little counterintuitive, researchers hope this investigation demonstrates that a wooden satellite can be more sustainable and less polluting for the environment than conventional satellites,” Meghan Everett, the deputy chief scientist for NASA’s International Space Station program, said in a press briefing on Monday (Nov. 4), a few hours before the Dragon capsule lifted off.

Conventional satellites are made primarily of aluminum. When they burn up in Earth’s atmosphere at the end of their lives, they generate aluminum oxides, which can alter the planet’s thermal balance and damage its protective ozone layer.

Related: Pollution from rocket launches and burning satellites could cause the next environmental emergency

These impacts are becoming more of a concern as the orbital population grows, thanks to the rise of megaconstellations like SpaceX’s ever-growing Starlink broadband network, which currently consists of about 6,500 active satellites.

Wooden satellites like LignoSat — which substitutes magnolia wood for aluminum — could be part of the solution going forward; they wouldn’t pump such damaging pollutants into the atmosphere when they fell back to Earth, mission team members have said.

“Metal satellites might be banned in the future,” retired Japanese astronaut Takao Doi, an aerospace engineer who’s now a professor at Kyoto University, told Reuters. “If we can prove our first wooden satellite works, we want to pitch it to Elon Musk’s SpaceX.”

LignoSat, which was developed by researchers at Kyoto University and the Tokyo-based logging company Sumitomo Forestry, will soon get a chance to prove itself.

About a month from now, the cubesat will be deployed into orbit from the ISS’ Kibo module. If all goes according to plan, its onboard electronics will record and beam home key health data for the next six months.

“Student researchers will measure the temperature and strain of the wooden structure and see how it might change in the vacuum environment of space, and the atomic oxygen and radiation conditions as well,” Everett said.

LignoSat team members also say a successful test could have implications far beyond Earth orbit.

“It may seem outdated, but wood is actually cutting-edge technology as civilization heads to the moon and Mars,” Kenji Kariya, a manager at the Sumitomo Forestry Tsukuba Research Institute, told Reuters. “Expansion to space could invigorate the timber industry.”