As a huge comet makes its closest approach to Earth on Wednesday (July 13), you might be curious why it’s so hard to spot.

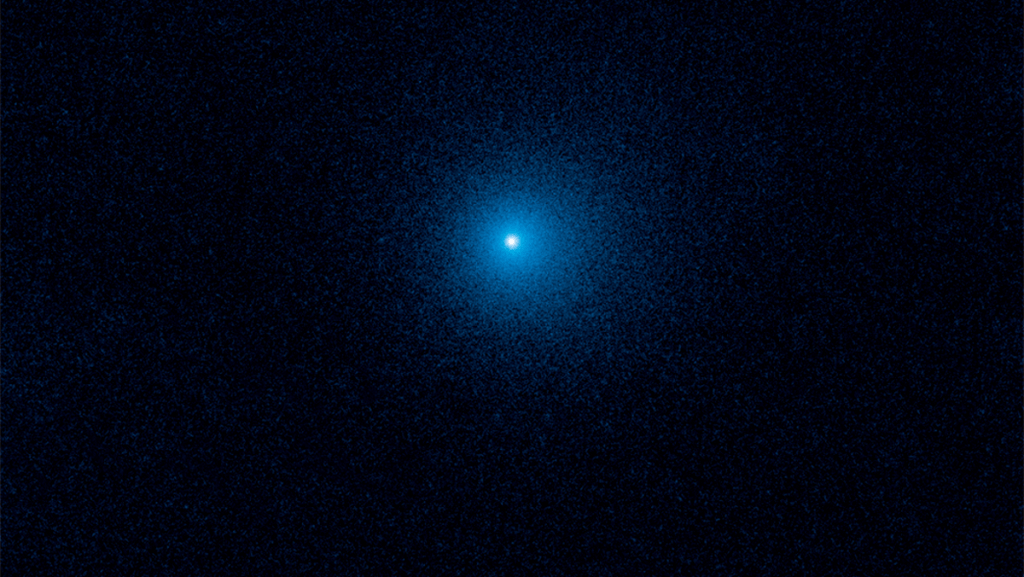

Comet C/2017 K2 (PANSTARRS), called K2 for short, is one of the farthest active comets ever spotted. First seen far out in the solar system in 2017, the comet will continue to brighten (assuming it survives) in the back half of the year as it reaches its closest approach to the sun on Dec. 19. But it likely won’t reach naked eye brightness.

EarthSky (opens in new tab) predicts, however, that Comet K2 will likely only get as bright as magnitude 7, which is just out of reach of naked-eye visibility. It’s puzzling given the comet’s large size; the nucleus could be as large as between 18 and 100 miles (30 to 160 kilometers) wide, from early observations by the Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope. (That estimate is contentious; Hubble Space Telescope observations suggested it might be only 11 miles, or 18 km, at most.)

Related: Giant comet was active way farther from the sun than expected, scientists confirm

Nevertheless, skywatchers’ problem with the comet isn’t its uncertain size; it’s that K2 will by at a relatively far distance from Earth.

The trouble comes because, as professional comet observer John Noonan told Space.com, the inherent brightness (or luminosity) of the comet is determined by its distance from our planet, as well as the amount of sunlight hitting its surface.

Noonan, a researcher at Auburn University in Alabama, has studied cometary outbursts before using the Hubble Space Telescope. Comet activity is related to surface temperature, he said, and more broadly, to how quickly surface ices sublimate (or turn directly from solid to gas) and generate dust.

When K2 was discovered in 2017 on its journey inward from the cold, distant Oort Cloud, it was spewing carbon monoxide that lifted a lot of dust as it sublimated. But the comet appears more muted as it swings closer to our planet.

“The activity of these comets from the Oort Cloud is difficult to predict, and rarely is the activity level increase of these comets accurately measured as they come into the inner solar system,” Noonan said.

Even if its activity were increasing, K2 will be rather far away during its closest approach to our sun. Distance determines how much light reflected from the dust coma makes it to our telescopes on Earth.

On July 13’s closest approach to our planet, Noonan said, the comet will be nearly two Earth-sun distances (1.8 astronomical units) away. That’s much too far away from the sun to generate a lot of sublimation and bright dust-lifting events.

Even when K2 gets to its closest approach to the sun in December, it will remain beyond the orbit of Mars at 1.8 astronomical units. The poor distance and dust production together, he said, make K2’s showing likely a poor one. “None of [these factors] line up for an excellent naked-eye apparition,” he said.

Quanzhi Ye, an astronomer at the University of Maryland who specializes in comets, told Space.com that K2’s closest approach to the sun in December will also be faint because the comet will be on the other side of the sun relative to our planet and roughly 2.5 astronomical units from Earth.

“It would easily have been a naked-eye comet had it arrived half a year earlier or later,” Ye said. “But on the plus side, it would stay at a brightness accessible by larger binoculars (about 8 magnitude) for almost a year.”

If you’re looking for binoculars or a telescope to see the comet in the night sky, check out our guide for the best binocular deals and the best telescope deals now. If you need equipment to capture the moment, consider our guides for the best cameras for astrophotography and the best lenses for astrophotography to make sure you’re ready for the next comet sighting.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).