British researchers have tested a prototype self-eating rocket that could pave the way for cheaper launches of small satellites and would leave no debris behind.

The concept rocket engine, called Ouroborous-3 after the ancient mythical creature that eats its own tail, was developed by a team of researchers at the University of Glasgow in the U.K.

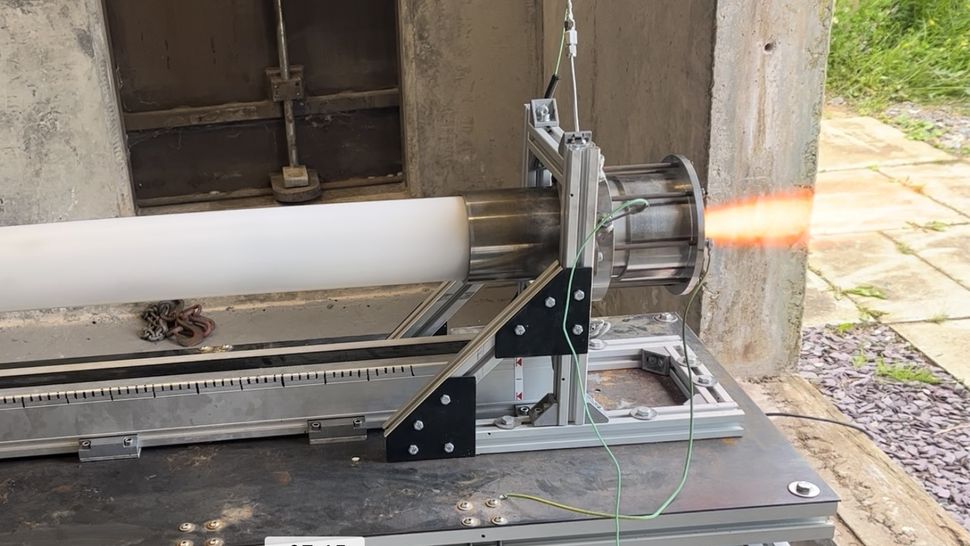

In the video, the rocket engine is seen gradually burning up like a candle until the final section suddenly collapses when the rocket runs out of fuel.

Related: Firefly Aerospace’s new rocket engine spouts green flames in 1st ‘hot fire’ test (photo)

The concept, originally proposed in the 1930s, was shown to be feasible in previous studies done in cooperation between the Glasgow team and researchers at the Dnipro National University in Ukraine. Since then, however, the teams have gone their separate ways. The Ukrainian development has spun out a company called Promin Aerospace, which has tested its own self-eating concept rocket in a lab and is currently looking for funding.

The rocket made by the Glasgow team burns gaseous oxygen and liquid propane in its engine. As the engine heats up, it melts the rocket’s supporting structure made of a plastic tube and burns it too. By burning this plastic, the rocket gains an additional 5 to 16 percent of fuel. As a result, the rocket can be lighter when it launches and have more room for payloads.

“A conventional rocket’s structure makes up between five and 12 percent of its total mass,” Professor Patrick Harkness, of the University of Glasgow’s James Watt School of Engineering, who led the development of the Ourouboros-3 self-eating engine, said in an email statement. “Our tests show that the Ouroborous-3 can burn a very similar amount of its own structural mass as propellant. If we could make at least some of that mass available for payload instead, it would be a compelling prospect for future rocket designs.”

Since the rocket burns most of its structure, it doesn’t produce as much debris as other rockets. Standard rockets contain fuel in separate stages. When a stage runs out of fuel, it gets dropped and either falls back to Earth or remains in orbit and turns into orbital debris.

The researcher said the self-eating technology could also enable the creation of very small rockets tailored for the smallest satellites, which currently have to piggyback on much larger missions.

The researchers put the rocket through its paces at the Machrihanish Airbase in Scotland and demonstrated that it can be throttled, reignited and pulsed. During the tests, the rocket produced 100 newtons of thrust, and the researchers are already working on a more powerful successor.

“Getting to this stage involved overcoming a lot of technical challenges but we’re delighted by the performance of the Ourouboros-3 in the lab,” Krzysztof Bzdyk, a postgraduate researcher at the James Watt School of Engineering and corresponding author of the paper, said in the statement. “From here, we’ll begin to look at how we can scale up autophage propulsion systems to support the additional thrust required to make the design function as a rocket.”

The team received £290,000 ($368,089) from the UK Space Agency and the U.K. Science and Technology Facilities Council to develop the rocket.

The researchers presented the results of the latest round of experiments at the AIAA SciTech Forum in Orlando, Florida, on Wednesday, Jan. 10.