Spending 45 years traversing the solar system really does a number on a spacecraft.

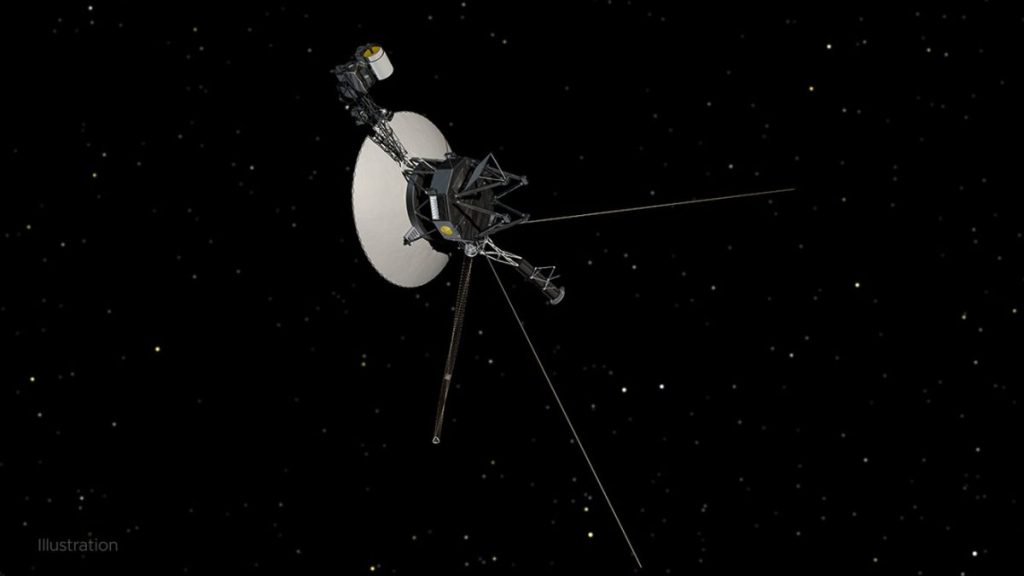

NASA’s Voyager 1 mission launched in 1977, passed into what scientists call interstellar space in 2012 and just kept going — the spacecraft is now 14.5 billion miles (23.3 billion kilometers) away from Earth. And while Voyager 1 is still operating properly, scientists on the mission recently noticed that it appeared confused about its location in space without going into safe mode or otherwise sounding an alarm.

“A mystery like this is sort of par for the course at this stage of the Voyager mission,” Suzanne Dodd, project manager for Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said in a statement.

Related: Pale Blue Dot at 30: Voyager 1’s iconic photo of Earth from space reveals our place in the universe

“The spacecraft are both almost 45 years old, which is far beyond what the mission planners anticipated,” Dodd added. “We’re also in interstellar space — a high-radiation environment that no spacecraft have flown in before.”

The glitch has to do with Voyager 1’s attitude articulation and control system, or AACS, which keeps the spacecraft and its antenna in the proper orientation. And the AACS seems to be working just fine, since the spacecraft is receiving commands, acting on them and sending science data back to Earth with the same signal strength as usual. Nevertheless, the AACS is sending the spacecraft’s handlers junk telemetry data.

The NASA statement does not specify when the issue began or how long it has lasted.

The agency says that Voyager personnel will continue to investigate the issue and attempt to either fix or adapt to it. That’s a slow process, since a signal from Earth currently takes 20 hours and 33 minutes to reach Voyager 1; receiving the spacecraft’s response carries the same delay.

The twin Voyager 2 probe, also launched in 1977, is behaving normally, NASA said. The power the twin spacecraft can produce is always falling, and mission team members have turned some components off to save juice — measures they hope will keep the probes working through at least 2025.

“There are some big challenges for the engineering team,” Dodd said. “But I think if there’s a way to solve this issue with the AACS, our team will find it.”

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.