Scientists have built the most detailed map volcanoes on Venus, which is also the most complete volcano map of all planets in the solar system.

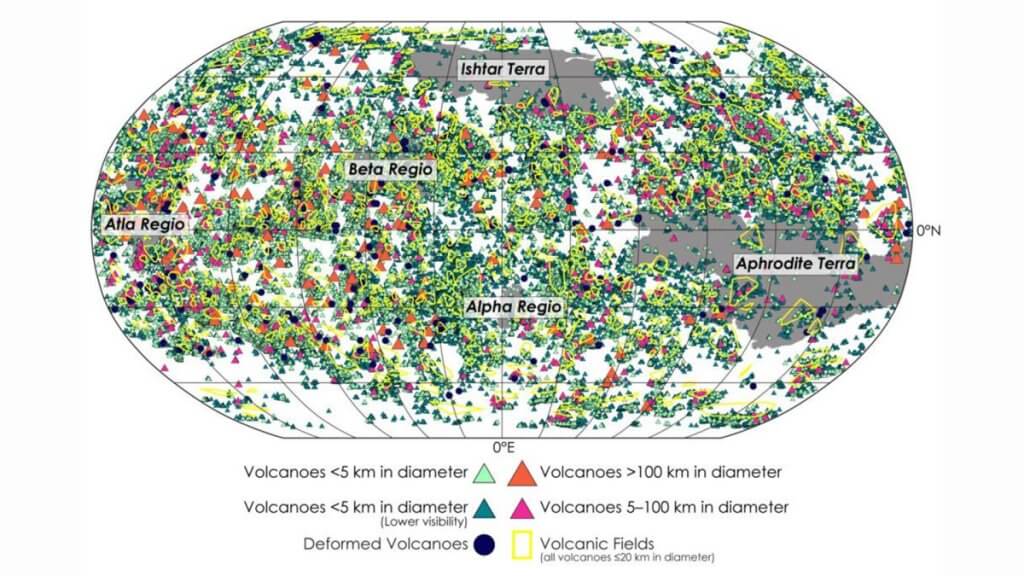

The map reveals the locations and sizes of all 85,000 volcanic landforms discovered on Venus to date, and the scientists hope that it will help with the search for new active volcanoes on Earth’s scorching planetary neighbor.

For years, scientists thought that Venus’ volcanism had long been extinct. Although Venus features more volcanoes than any other planet in the solar system, it doesn’t have tectonic plates, which drive volcanic activity on Earth.

A discovery of a recently active volcano on Venus announced earlier this year, however, renewed interest among planetary scientists to look for more such live volcanoes on the planet’s blistered surface.

“This new database will enable scientists to think about where else to search for evidence of recent geological activity,” Paul Byrne, an astronomy professor at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, and the study’s co-author, said in a statement (opens in new tab).

Related: Planet Venus: 20 interesting facts about the scorching world

The map, released Thursday (March 29), is the most complete catalog of volcanism on any world, including Earth. Most of Earth’s volcanoes are yet to be found because they are hidden underwater on the planet’s ocean floor. Venus, however, being the parched world it is, displays all volcanoes on its surface, allowing scientists to spot and study most if not all of them.

Byrne’s team made the catalog publicly available (opens in new tab) for other scientists to analyze. “I’m excited to see what they can figure out with the new database!” Byrne said.

The team hopes the new catalog will provide better understanding about how volcanoes of various sizes form, spread and evolve across the surface of Venus.

“We came up with this idea of putting together a global catalog because no one’s done it at this scale before,” Rebecca Hahn, a graduate student in earth and planetary sciences at Washington University and first author of the new paper, said in the statement.

At the moment, the only information astronomers have about volcanism on Venus is from images sent home by NASA’s Magellan spacecraft in the early 1990s. The team behind the latest study used that 30-year-old data to put together the comprehensive inventory of Venusian volcanoes.

Researchers categorized all volcanoes in the database into three groups based on their sizes: small landforms less than 3 miles (5 kilometers) in diameter, intermediates of sizes between 3 to 62 miles (5 to 100 km) and large volcanoes more than 62 miles (100 km) wide.

The map revealed that numerous small volcanoes, which were previously overlooked by volcano hunters, make up much of the catalog, according to the study. “They’re the most common volcanic feature on the planet: they represent about 99% of my dataset,” Hahn said. On the other end of the spectrum of volcanic sizes, the team found that large volcanoes are few in number, and are clustered near the Venusian equator.

The team also found that volcanoes on Venus have a tendency to be either very small or quite large, as the latest catalog showed surprisingly few volcanic landforms of intermediate sizes. Such moderately sized landforms were found to be huddled on the planet’s eastern hemisphere. Interestingly, the team did not find any volcanoes around the planet’s south pole, although why that is the case is a mystery.

Scientists say these findings shed more light on the processes occurring in the interior of Venus. The number of volcanoes and their sizes could be explained by specific amounts of magma swirling underneath the planet’s surface, or by the rates at which volcanoes erupt on Venus, according to the study.

Although the latest catalog unveils 50 times more volcanoes than what researchers thought existed on the planet’s surface, the team thinks there are more waiting to be discovered. For example, extremely small volcanoes spanning just 0.6 miles (1 km) in diameter are too tiny to be spotted in the old Magellan data.

Scientists hope such small volcanoes will be found by NASA’s Venus mission VERITAS, which is designed to see through the planet’s thick atmosphere and has the ability to notice centimeter-sized changes on its surface. However, NASA recently pulled a bulk of the mission’s funding, delaying VERITAS — the first of three long awaited Venus missions — indefinitely.

The news of the mission’s delay came just a few days before the discovery of the active volcano on Venus, which has made the Venus community hungry for missions to the planet that would be able to study its volcanism in greater detail. “This is one of the most exciting discoveries we’ve made for Venus – with data that are decades old!” Byrne said. “But there are still a huge number of questions we have for Venus that we can’t answer, for which we have to get into the clouds and onto the surface.”

The research is described in a paper (opens in new tab) accepted for publication in the journal JGR Planets.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg (opens in new tab). Follow us @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab), or on Facebook (opens in new tab) and Instagram (opens in new tab).