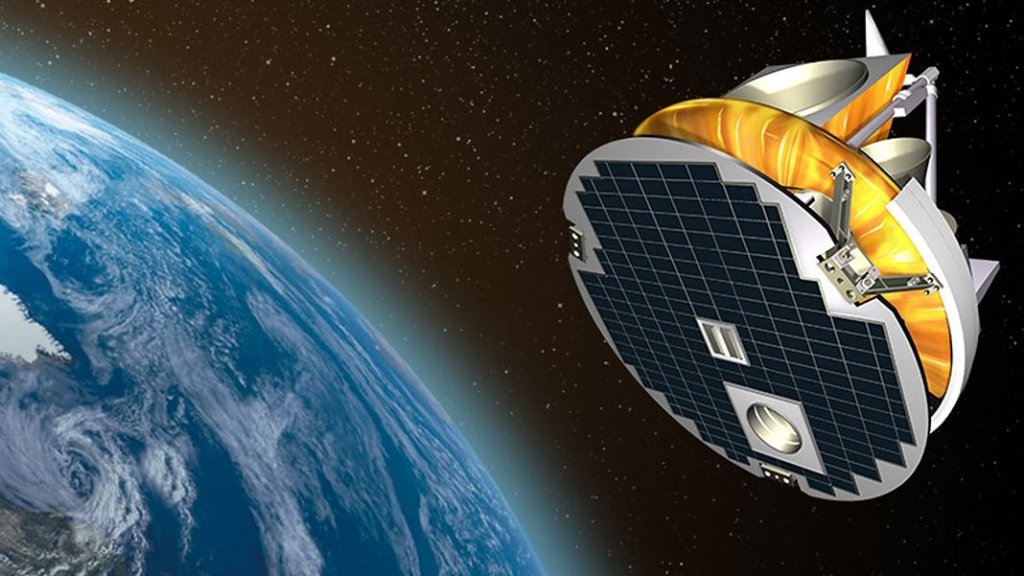

The satellite was only supposed to last two years. But it’s still healthy at 20.

Canada’s Scisat is defying all lifetime expectations at a crucial time in human history, helping track the effects of human-driven climate change. Throughout its long lifespan — its 20th launch anniversary fell on Aug. 12 — Scisat has been providing consistent data to help us heal Earth’s atmosphere, if we take the time to pay attention.

Three things have allowed the Canadian Space Agency to keep operating the satellite for so long, program lead Marcus Dejmek told Space.com. First, the satellite needs little fuel to stay stable in its orbit. Data products are also constantly tweaked to track more gases and chemical species, even with aging (if healthy) instruments. Finally, a fit satellite and constant updates together allow Scisat to deliver relevant products for its users, driving enough demand to keep government budgets flowing.

“Also, I wouldn’t be doing my job if I didn’t say that part of this answer was to have a dedicated group of staff that operate and understand the spacecraft hardware over time,” Dejmek emphasized. Just like a car, satellites need servicing, but instead of oil changes, the little Scisat receives software updates and hardware adjustments. “The people there are just great, and they’re the frontline of the success.”

Related: Earth is getting hotter at a faster rate despite pledges of government action

Scisat was developed and built for $63 million CAD in 2003 (roughly $97 million CAD or $71 million USD at today’s rates, although inflation differs between the two countries.) NASA flew it for free on Pegasus, which is an air-launched rocket now operated by Northrop Grumman. That flight was in exchange for Canada’s robotics contributions to the space shuttle program (the spacecraft was still running then) and the International Space Station, which pays for science and astronaut seats.

Related: Artemis 2’s Canadian astronaut got their moon mission seat with ‘potato salad’

The small satellite — only about the area of a queen-sized bed — uses two scientific instruments to identify gases and particles in Earth’s atmosphere. Under scientific leadership from a coalition of Canadian universities, Scisat scrutinizes erosion of our planet’s protective ozone layer. This layer blocks harmful radiation from the sun before the rays reach Earth’s surface.

Among Scisat’s many achievements is finding pollutants in the atmosphere never spotted from space before. An example is the refrigerant gas HCFC-142b, which was used to replace chlorofluorocarbons. Chlorofluorocarbons were a common product in refrigerants, foams, aerosol sprays and solvents until the late 1980s. The ozone-eroding substances are not as common today after the Montreal Protocol of 1987; nations that signed that protocol gradually phased such substances out.

Scisat also tracks atmospheric pollutants like soot and other particles from forest fires. This year has been Canada’s worst on record for wildfires. A chunk of the country equivalent to the size of Greece has been burned already, Canadian federal data indicates: 51,000 square miles (13.3 million hectares). That size is nearly seven times Canada’s yearly average over the past decade.

As it’s only August, the season is not nearly over; this month, a raging wildfire in the Northwest Territories sparked evacuations of the city of Yellowknife. Another set of Quebec wildfires in June created smoke so thick that Venus-like yellow skies glowed above New York City. The plume even carried across the ocean to Europe.

Related: Smoke from Canadian wildfires chokes US Midwest, reaches Europe (satellite photos)

“It’s clarified that there should be a growing concern that more frequent and intense wildfires are eroding the ozone layer, and they could therefore ‘delay the ozone recovery in a warming world,'” Dejmak said of Scisat, quoting a March 2023 Nature paper using the mission’s data.

Scisat not only tracks pollutants but can help map them out by altitude. An instrument known as a Fourier transform spectrometer allows the satellite to gaze at trace gases below in vertical distribution, which essentially means in slices of Earth’s atmosphere. Both of Scisat’s instruments also record spectra (light signatures) of sunlight shining through the atmosphere; this process lets scientists analyze chemical elements in the air.

And that’s not all Scisat has done recently. In a Science publication, scientists tracked water vapor in the stratosphere from the massive Tonga volcano eruption of 2022. The satellite has generated at least 70 high-impact papers since its launch 20 years ago, Dejmak said. The data will continue to be useful even after the mission eventually ends no sooner than 2024, based on current funding.

While Canada is not building a direct successor for Scisat yet, the country is in the early stages of developing WildFireSat, which would be optimized to track active fires and to alert first responders on the ground as early as possible.

The 20-year-old Scisat also brings up an issue that has also been discussed in NASA and European Space Agency circles: making sure that new missions go up to replace or enhance the satellites that will eventually age out.

NASA’s Karen Germain, director of the agency’s Earth Science Division, spoke in a July 20 livestreamed climate change event about how important it is to keep a variety of missions in space.

“This wide diversity of observations sustained over time has taught us much of what we understand about how and why the Earth system, including climate, is changing,” she said, noting the science includes aspects like the energy cycle, climate variability and changes in the atmosphere.

“Our science isn’t done until we’ve communicated it,” Germain added, saying that is especially true when it comes to public safety. “This has never been more important or compelling than it is today.”