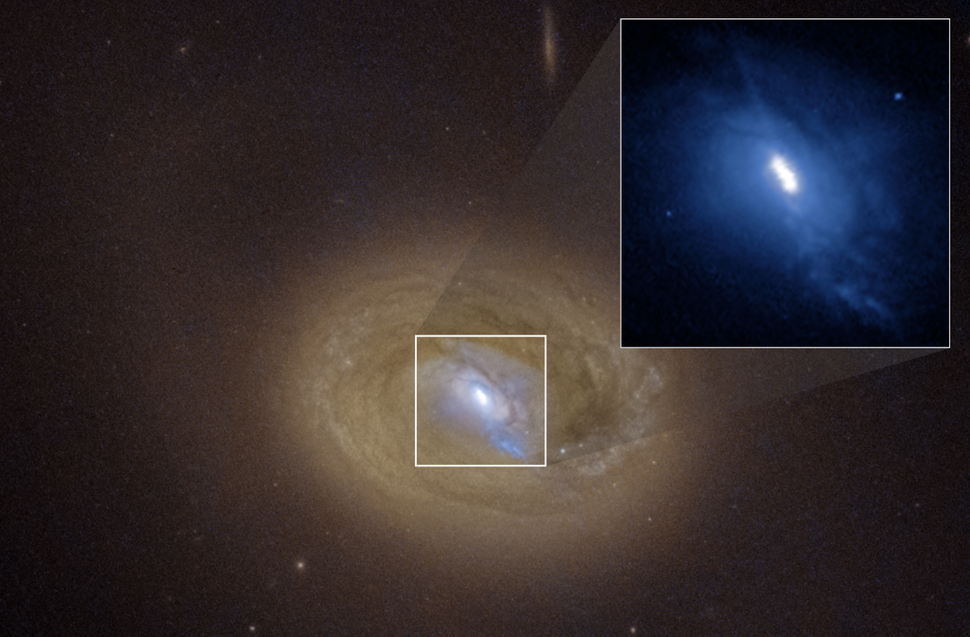

It’s the ultimate telescope vs. supermassive black hole tag-team match as the NASA team of Chandra and Hubble pin down a supermassive black hole pairing! Not only was this black hole tag team surprisingly close to Earth, but they were also in tight proximity to each other!

The supermassive black holes are located in the merging galaxies MCG-03-34-64, around 800 million light-years away, and are separated from each other by just 300 light-years.

That’s not all. These two black holes actively gobble gas and dust falling to them from their surroundings, powering bright light emissions and powerful outflows or jets. Such regions are referred to as “active galactic nuclei” or “AGNs,” and they can often be so bright that they outshine the combined light of every star in the galaxies that surround them.

Despite being an almost incomprehensibly vast distance from Earth, this pairing is still the closest AGN pairing seen in multiple wavelengths of light. Hubble observed it in visible light, and Chandra saw it in X-rays. A pair of supermassive holes closer together than this one has been discovered, but it was detected only in radio waves and has not been confirmed in other wavelengths, according to NASA.

The supermassive black holes at the heart of MCG-03-34-64 are also closer to each other than the occupants of previously discovered binaries of this type. They would have both been at the centers of their own respective galaxies at one time, with a collision and merger between those galaxies bringing them close together.

The two supermassive black holes won’t stay as widely separated as this, either. As they swirl around each other, the binary will emit ripples in spacetime called “gravitational waves.” As these gravitational waves ring through space, they carry angular momentum away from the black holes, causing them to draw together and emit gravitational waves faster and faster.

This will continue for around 100 million years until the supermassive black holes are so close together that their immense gravity takes hold, and they are forced to collide and merge like their parent galaxies once did.

Related: Small black holes could play ‘hide-and-seek’ with elusive supermassive black hole pairs

AGN binaries similar to this one are thought to have been common in the early universe billions of years ago when mergers between galaxies were more common. This pairing provides a unique opportunity to observe such a binary that is much closer to home than those that existed billions of years ago and are thus billions of light-years away.

Hubble gets lucky

This discovery is an example of how serendipity can play a role in astronomy. Hubble spotted the AGN in data that indicated a dense concentration of oxygen within a very small region of MCG-03-34-64.

“We were not expecting to see something like this,” team leader Anna Trindade Falcão of the Center for Astrophysics|Harvard & Smithsonian said in a statement. “This view is not a common occurrence in the nearby universe, and told us there’s something else going on inside the galaxy.”

To solve the mystery of what is occurring in MCG-03-34-64, Falcão and colleagues turned to Chandra to examine the same region, this time using X-rays.

“When we looked at MCG-03-34-64 in the X-ray band, we saw two separated, powerful sources of high-energy emission coincident with the bright optical points of light seen with Hubble,” Falcão continued. “We put these pieces together and concluded that we were likely looking at two closely spaced supermassive black holes.”

The team didn’t stop there. They drafted in some help for this space telescope tag team in the form of archival data from the Earth-based Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) located near Socorro, New Mexico. This revealed that the supermassive black hole pairing at the heart of this AGn are also belting out powerful radiowaves.

“When you see bright light in optical, X-rays, and radio wavelengths, a lot of things can be ruled out, leaving the conclusion these can only be explained as close black holes,” Falcão continued. “When you put all the pieces together, you get a picture of the AGN duo.”

Hubble saw a third bright light source in the AGN, which remains somewhat mysterious. The team suggests that this could be gas that has been “shocked” by a jet of high-speed plasma launched by one of the supermassive black holes, almost like a jet of water from a garden hose blasting a mound of sand.

The findings prove that even after three decades in space, Hubble is still delivering cutting-edge science results.

“We wouldn’t be able to see all of these intricacies without Hubble’s amazing resolution,” Falcão concluded.

The team’s research was published on Monday (Sept. 9) in The Astrophysical Journal.