A slice of space rock no larger than a credit card could run up a big sale price at a Christie’s auction in the next few days.

The item up for bid is a small piece of the first recorded meteorite seen as it dropped through the sky and landed in a wheat field. In some history books and manuscripts, it was the only major world event mentioned for the year that it fell to Earth — 1492.

“This is back in a time before there was scientific consensus that meteorites actually existed,” said James Hyslop, head of scientific instruments, globes, and natural history for the auction house, “So this was very much seen as something sent by the Divine.”

It’s not the first time a piece of the famed Ensisheim meteorite(Opens in a new tab) has hit the auction block — small chips weighing mere ounces have appeared at Christie’s and its competitor Sotheby’s(Opens in a new tab) before — but it remains a popular and intriguing item for collectors because of its historical significance and story.

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

As of Friday, it had already racked up over 20 online bids and was nearing $3,000, with four days remaining before the auction closes March 28. The last time Christie’s had a piece to sell — a heavier, half-ounce sample in 2021(Opens in a new tab) — it went for $15,000.

“This was very much seen as something sent by the Divine.”

The origin of meteorites

Scientists estimate about 48.5 tons of billions-of-years-old meteor material rain down on the planet daily, but recovering them is still like finding a needle in a haystack: Much of the rubble vaporizes in Earth’s atmosphere or falls into the ocean, which covers over 70 percent of the planet.

More than 60,000 space rocks have been discovered on Earth. The vast majority of them come from asteroids, but a small fraction, about 0.2 percent(Opens in a new tab), comes from Mars or the moon, according to NASA. At least 175 have been identified(Opens in a new tab) as originating from the Red Planet.

Credit: Manfred Schmid / Getty Images

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

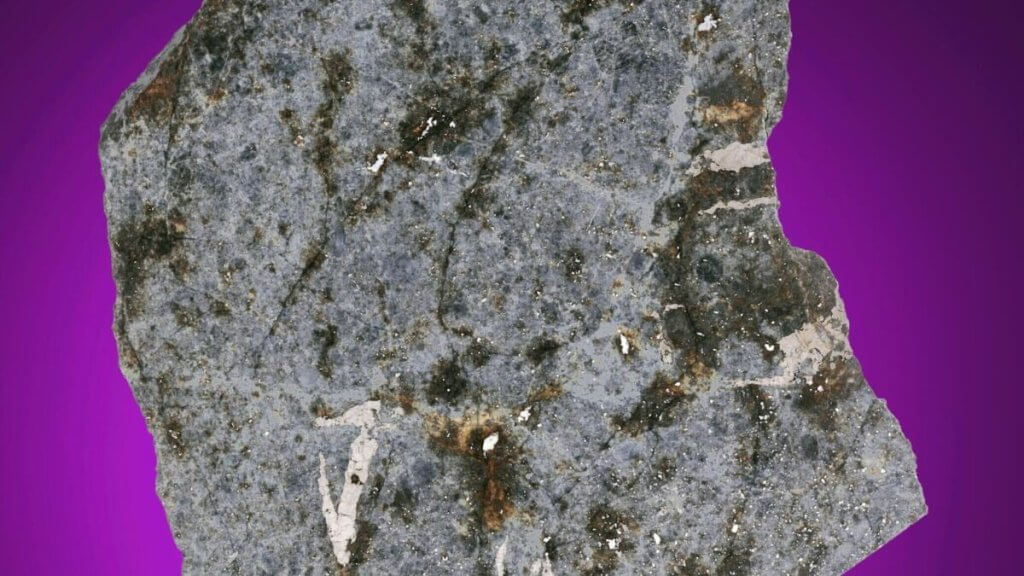

The Ensisheim meteorite is known as an ordinary chondrite, the most commonly found sort of alien rock on Earth. But in medieval times, there were no words to describe such a marvel. It would take about 300 more years(Opens in a new tab), after several meteorite sightings in Europe and the United States in the early 1800s, for scientists to accept that rocks could fall from space.

Weeks after Christopher Columbus reached the Bahamas, the meteorite struck near the Alsatian town of Ensisheim(Opens in a new tab) in France, according to The Meteoritical Society. A young boy saw it firsthand on Nov. 7, 1492, and brought residents to the 280-pound black stone, to gawk at its perplexing fusion crust and the one-yard-deep hole it bore into the ground. People 100 miles away from the crash site in the Alps heard the fireball’s boom, unlike any thunderclap.

Credit: Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Townspeople swiped chunks of the rock, believing it to be a good luck charm before city leaders forbade the vandalism. Twenty days later, Roman Emperor Maximilian I interpreted the Ensisheim event as a sign from God to declare war on France.

Within a month or so of the meteorite’s fall, renowned poet Sebastian Brant wrote about the Ensisheim rock, describing it as a triangular stone that emerged from a storm cloud, burning on its way to the ground. At the time it was referred to as the thunderstone, and he alleged it was marked with a cross.

The story, a form of early journalism, was published on one-sided bulletins and dispersed in surrounding cities. The verses, originally printed in Latin and German with woodblock engravings, were translated and pirated, causing word to spread of the mysterious stone, according to a paper written by planetary geologist Ursula B. Marvin on the meteorite, published around its 500th anniversary(Opens in a new tab) in the journal Meteoritics.

The poet Brant was also responsible for putting it in a political context: He claimed it was a bad omen for the French side.

Credit: Getty Images

Maximilian was indeed victorious in battle. He gained territory and brought back his daughter, who was with the French King, Charles VIII. The fact that the event happened shortly after the advent of the printing press in the mid-1400s — and was used in wartime propaganda — was what made it memorable and unprecedented, Marvin said.

“Impressive as the stone and explosion were,” she wrote, “the latter two factors were crucial for winning a place in history for the Ensisheim meteorite.”

Ensisheim meteorite for sale

Maximilian ordered that the main portion of the rock be hung in the town’s church, and it remained there until 1793, Marvin said, intriguing visitors with a Latin inscription(Opens in a new tab): “Many have spoken of this stone, all said something, nobody has said enough.”

Credit: Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Over the years, many museums and galleries obtained pieces of the meteorite, with a large amount going to the Vatican, Hyslop told Mashable, because it was the first institution to collect such objects thought to be sent from God. Some ended up in Paris, and some went to the precursor for the Natural History Museum of London.

In order for space rocks to get formally cataloged as meteorites, large pieces have to be kept at designated natural history museums for preservation. But the London museum exchanged some of its hunk 30 years ago for newly found meteorites that originated from the moon and Mars, Hyslop said. That’s how a private collector got a hold of the piece Christie’s is selling today.

The whittled away portion of the rock, now about 117 pounds, remains in Ensisheim.

“It’s the sort of meteorite that if it was just found on its own, and didn’t have that 500-year history behind it, it wouldn’t be hugely sought after,” Hyslop said. “It has such a long pedigree to it.”