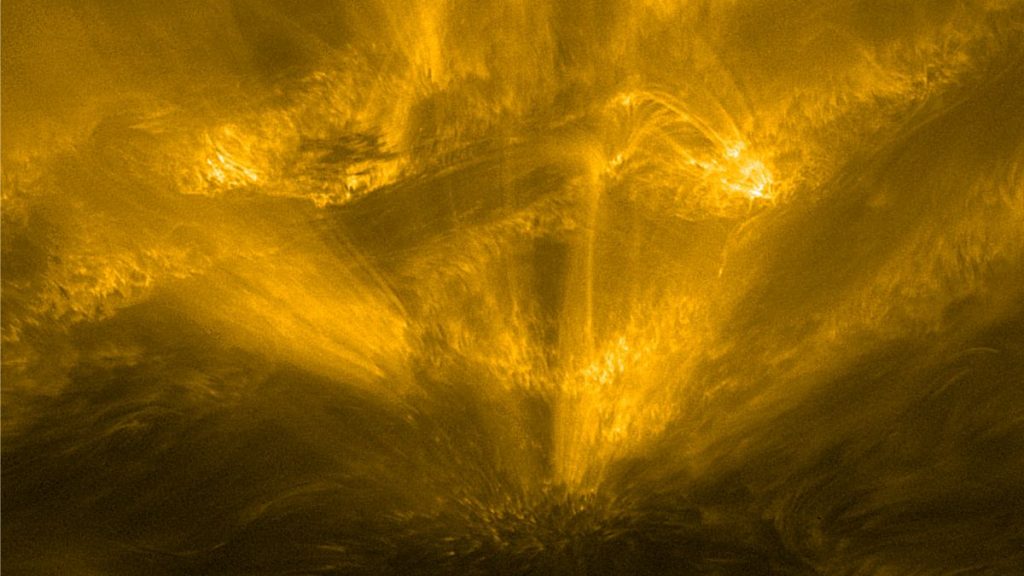

A new record-breaking set of images of the sun captured by the Solar Orbiter probe during its close pass of the star in March has been released, revealing a plethora of never-before-seen details, including a curious geyser of gas scientists have nicknamed the “solar hedgehog.”

During the pass, which took Solar Orbiter as close as one-third of the sun-Earth distance, the spacecraft also glimpsed the sun’s south pole. It was the first time that any telescope, space- or Earth-based, had captured such detailed images of this region of the sun, which scientists believe plays a key role in the generation of the sun’s magnetic field.

“The images are really breathtaking,” David Berghmans, a solar physicist at the Royal Observatory of Belgium and the lead scientist of the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager instrument on Solar Orbiter, said in a statement from the European Space Agency (ESA), which leads the mission. “Even if Solar Obiter stopped taking data tomorrow, I would be busy for years trying to figure all this stuff out.”

Related: Solar Orbiter spacecraft captures huge eruption on the sun (video)

The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager is responsible for the most stunning images captured by the spacecraft, which was launched in February 2020. The camera reveals in high resolution phenomena in the lower layers of the sun’s atmosphere, the region responsible for the generation of solar flares and coronal mass ejections, which are outbursts of magnetized plasma from the outer atmosphere, known as the corona.

Among the never-before-seen phenomena captured around the close pass on March 26 was a strange geyser of hot and cold gas emanating from the sun’s surface in all directions that the scientists dubbed the “solar hedgehog.”

Stretching 15,500 miles (25,000 kilometers), twice the diameter of Earth, the “hedgehog” covers a small fraction of the sun’s diameter of 865,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) but is much larger than the country-sized mini solar flares called campfires discovered during the spacecraft’s first close pass at the sun in June 2020. At that time, Solar Orbiter was still in the so-called commissioning phase and not in the full science mode, and it only approached the star as close as half the sun-Earth distance.

“We are so thrilled with the quality of the data from our first perihelion [the closest point in a body’s orbit to the sun],” Daniel Müller, Solar Orbiter project scientist at ESA, said in the statement. “It’s almost hard to believe that this is just the start of the mission. We are going to be very busy indeed.”

The images of the sun’s south pole taken during the close pass are of special interest to scientists studying the behavior of the sun and its 11-year-long cycle of activity, the periodic ebb and flow in the generation of sunspots, solar flares and eruptions.

At the height of this cycle, the sun’s magnetic poles flip, the magnetic north becoming south and vice versa, according to NASA. By measuring in detail what is happening in the sun’s polar regions, solar physicists hope to crack the mystery of this strange behavior.

Studying the sun’s poles is one of the key tasks of the Solar Orbiter mission. In the later part of the mission, the spacecraft’s operators will tilt the spacecraft’s orbit out of the ecliptic plane, in which planets orbit, to allow it to get a more direct view of the poles, something that has never been done before.

The March 26 close pass came at a time of rather intense solar activity. The spacecraft was in the firing line of several solar flares and a coronal mass ejection, which later triggered geomagnetic storms and radio blackouts on Earth.

“We’re always interested in the big events because they produce the biggest responses and the most interesting physics, because you are looking at the extremes,” Robin Colaninno, a solar physicist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, which developed the SoloHI PI instrument for Solar Orbiter, said in the statement.

Out of the 10 instruments aboard Solar Orbiter, four measure the properties of solar particles that reach the spacecraft. In the weeks around the close pass, the instruments detected several odd events that scientists are still analyzing. Researchers hope to be able to create connections between what the cameras, such as the EUI, see on the solar surface and what is going on in the environment around the star. Ultimately, they would like to be able to predict in greater detail the effects these flares and coronal mass ejections have on Earth.

Solar Orbiter will make its next close pass at the sun on Oct. 13, getting slightly closer to the star than in March. That means new record-breaking images can be expected. The spacecraft’s previous close passes took place at about half the sun-Earth distance.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.