The more evolved a galaxy is, the more collectively chaotic the orbits of its many stars are, new research shows, answering a key detail about how galaxies age.

Our sun orbits the center of the Milky Way galaxy once every 225 million years, at a velocity averaging 514,495 mph (828,000 kph). Astronomers call this a “galactic year.” The sun’s path around the galaxy is nearly circular, although it does bob up and down somewhat relative to the plane of the galaxy.

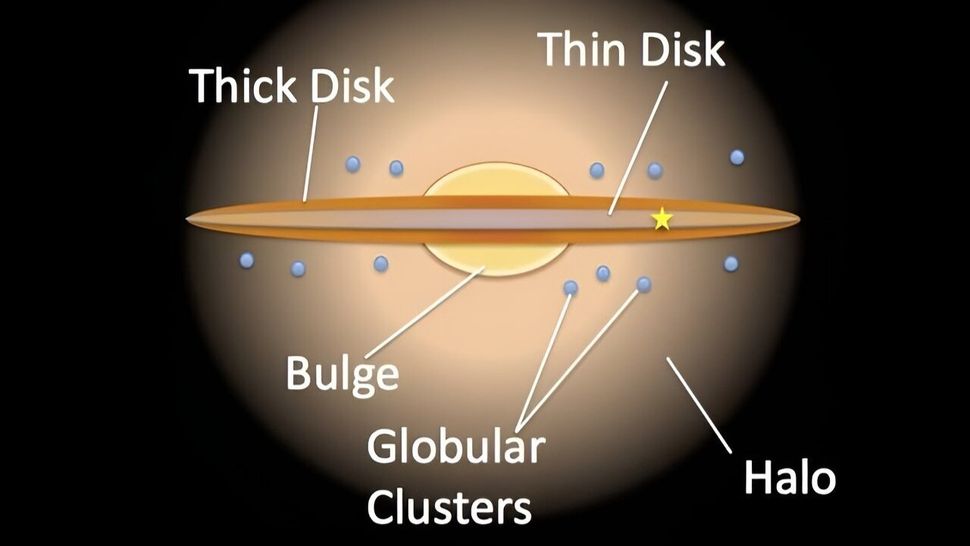

In other galaxies, however, the motions of stars have a greater degree of randomness, with their orbits adopting a wide variety of velocities and angles relative to the plane of their galaxy. In elliptical galaxies, this is often easy to explain: It’s the result of a major galaxy merger that formed the elliptical galaxy and stirred up all the stars like a hornet’s nest. But these random motions can dominate in disk galaxies, too. This is strange, since stars in a disk galaxy form in a narrow, gas-rich plane called the “thin disk.” Indeed, our Milky Way galaxy has a thin disk, inside which we find our sun and most of the stars visible to the unaided eye in the night sky. It’s the motion of these stars and gas clouds that create the apparent rotation of a galaxy.

Related: Milky Way galaxy: Everything you need to know about our cosmic neighborhood

Stars in the thin disk take a more or less circular route around a galaxy, traveling in ordered fashion because of collisions between the molecular gas clouds that formed these stars. This has the effect of smearing out any extreme motions, narrowing what is called the “velocity dispersion,” which describes the difference between the fastest and the slowest orbital velocities. A low-velocity dispersion should see most stars on circular orbits, whereas a high-velocity dispersion results in more random orbits.

Previous studies have found that a galaxy’s mass and how densely packed its environment is with neighboring galaxies may both play a role in controlling the propensity for random stellar motions. However, new research led by Australian astronomers finds that mass and environment are not the direct reason for the random motions, and that the real cause is something more insidious: age.

The “age” of a galaxy does not necessarily describe how long that galaxy has existed; it is thought that galaxies all formed in roughly the same era, around 13 billion years ago. Rather, age in this case is a condition, referring directly to a galaxy’s star-forming activity. A galaxy still giving birth to new stars is considered “younger,” while one in which star formation has ceased is described as “old.”

“When we did the analysis, we found that age … is always the most important parameter,” Scott Croom of the University of Sydney, who led the research, said in a press statement. “Once you account for age, there is essentially no environmental trend, and it’s similar for mass. If you find a young galaxy, it will be rotating, whatever environment it is in, and if you find an old galaxy, it will have more random orbits, whether it’s in a dense environment or a void.”

However, age and environment — and environment and galaxy mass — are each linked. For instance, galaxies in a denser environment tend to experience more collisions and mergers with other galaxies, and subsequently grow in mass faster.

Furthermore, “we do know that age is affected by environment,” said team member Jesse van de Sande, who is also from the University of Sydney. “If a galaxy falls into a dense environment, it will tend to shut down star formation. So galaxies in denser environments are, on average, older.”

Related: Galaxies: Collisions, types and how they’re made

There are two ways that star formation can be shut down inside a galaxy. One is through a phenomenon known as “ram-pressure stripping” — the thick, hot gas that inhabits galaxy clusters is able to heat a galaxy’s gas as it plunges into the cluster. This causes the gas to be stripped out of the galaxy, leaving it without any material to form new stars.

In dense environments, gravitational interactions between nearby galaxies can also stir up a galaxy’s gas and prompt it into a frenzy of star formation called a “starburst.” Feedback in the form of radiation from hot, newly born stars in a starburst, or from jets coming from an active supermassive black hole that has switched on thanks to a large amount of matter funneled toward its maw by the interactions, can heat the gas in a galaxy and blow it into intergalactic space, preventing it from forming stars.

Croom and van de Sande’s team conclude that the blame for the random stellar motions seen in older galaxies can be laid firmly at the feet of a combination of age-related effects. One is stars that are born “hotter” (meaning they are too energetic to adopt boring circular orbits) early in the life of a galaxy, followed by feedback from them that acts to quickly quench any further star formation before the galaxy has a chance to build a thin disk of stars with a lower velocity dispersion.

Our Milky Way galaxy, it seems, was one of the lucky ones. Its thin disk has an estimated age of 8.8 billion years. That thin disk, which is about 350 light-years deep, is embedded in a “thick disk,” which is a much older torus of ancient stars. Those stars were born hotter with more random motions, which contributes to the thick disk being 1,000 light-years deep, as those random motions are at steeper angles to the galactic plane.

The conclusions of Croom and van de Sande’s team are based on observations of 3,000 galaxies across a variety of ages, masses and in different environments, all by the SAMI (Sydney-AAO Multi-object Integral field spectrograph) Galaxy Survey that is being conducted on the Anglo-Australian Telescope at Siding Spring Observatory in Australia. The results were published on April 3 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.