Ukraine could be a space technology superpower but the country is held back by “Stalin-esque” attitudes that treat experts like peasants, says American aerospace engineering student Aaron Harford who chose Ukrainian capital Kyiv for his Ph.D. studies four years ago.

A mid-life divorce prompted Harford, at that time a math professor at Henderson State University in Arkansas, to uproot his life and fulfill his two life-long dreams: to spend time in Ukraine, the homeland of his ancestors, and to pursue a Ph.D. in aerospace engineering. The experience turned out to be even more life-changing than he had expected. Not only did he witness the build-up to the most serious armed conflict in Europe since World War II, but has also gained unique insights into the ailments of a place that has all the prerequisites to be a technology superpower, but is held back by more than 30-year-old ghosts of an overthrown political regime.

It might sound surprising that a third generation American from California who spent a short time working with start-ups in the Mojave Desert, one of the world’s most exciting new space hubs, would want to study aerospace engineering in Ukraine. To Harford, however, the idea makes a lot of sense. The Eastern European country, wedged between Russia (its one-time superior from the times when both were part of the Soviet Union) and the European Union, may have a gross domestic product per capita of about one 17th of that of the United States. It, however, boasts a population exquisitely educated in sought-after STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering &Mathematics) disciplines and a history full of big names from the early days of aviation and space engineering.

Live updates: Russia’s Ukraine invasion and space impacts

Related: Ukraine’s proud space industry faces obliteration, but former space chief hopes for the future

STEM powerhouse

For example, the school where Harford enrolled in 2018 is the Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute (KPI), named after its famous alumni, a legendary helicopter designer who in 1919 immigrated to the U.S. where he founded the Sikorsky Aircraft company, which is today owned by Lockheed Martin.

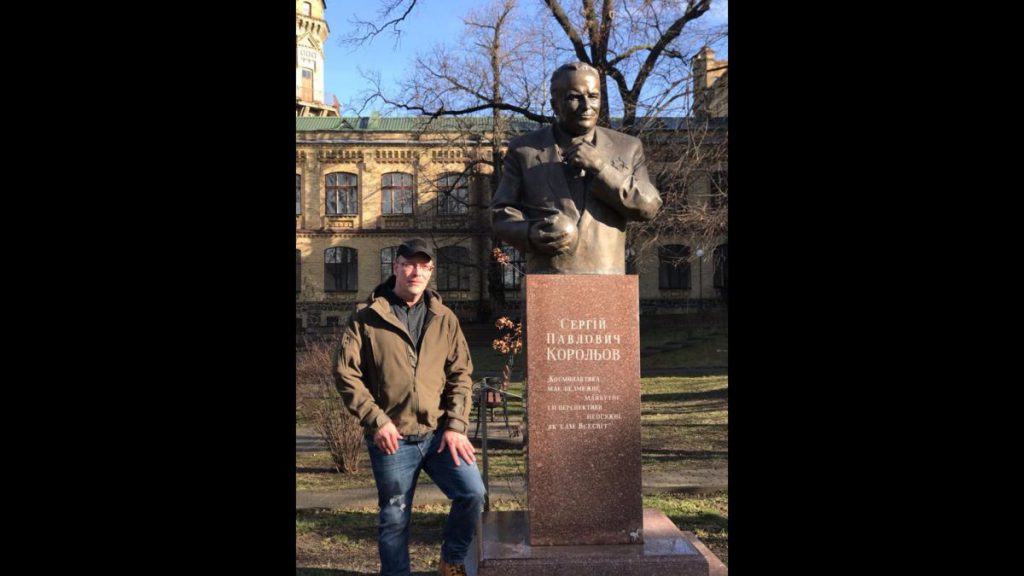

Sergei Korolev, the architect of the Soviet Union’s early space successes (including the first artificial satellite Sputnik 1 and the first human in space Yuri Gagarin), also studied at KPI. Yuri Kondratyuk, the physicist that first developed the theoretical concept of a lunar landing, was also a Ukrainian.

This legacy of science and exploration, Harford told Space.com, is not only still alive in Ukraine, but thriving. Ukraine owns one of the largest rocket factories in Europe — Yuzmash — which manufactures, among others, first stages for Northrup Grumann’s Antares rockets that launch the Cygnus spacecraft to the International Space Station. Over 16,000 people work for corporations managed by Ukraine’s national space agency.

“Their engineers, scientists and technicians are world class,” Harford said. “That’s a fact. Technologies like Hall Effect Thrusters [a type of spacecraft propulsion that uses a stream of accelerated ions to generate motion] were developed and are still perfected here. You can just walk into a lab and see them running tests on them.”

Ukraine, Harford said, is a great springwell of engineering talent. According to a report by software development outsourcing company N-iX, 130,000 young people graduate every year in Ukraine (a country with a population of 44 million) in engineering disciplines. That is about as much as in Europe’s traditional (and nearly twice as populous) technology powerhouse Germany (based on data from the website Studying in Germany).

A “Stalin-esque” legacy

This technological utopia, however, is struggling to shake off what Harford describes as a “Stalin-esque legacy.” Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union, a federation of Eastern European republics led by Russia, for nearly 70 years. Socialist central planning as opposed to commercial competition ruled the economy of that era together with oppression of political dissenters. Ukraine’s aerospace research establishments were built in those times. Even 30 years after Ukraine’s separation, the remnants are still very much present.

“The higher education system in Ukraine is perhaps the most Stalin-esque of all the institutions here,” said Harford, referring to Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin, the despot who led the Soviet Union in its glory years from 1922 to 1953. “They do not value their people appropriately. The staff here, the Ph.D.s, they are all very highly educated, highly intelligent and highly skilled professionals, but they are making three, four, five hundred dollars per month. You can’t live on that in Kyiv. It’s like a continuation of being a Soviet peasant.”

KPI’s campus, Harford admits, in spite of the cutting-edge research, is not a vibrant international hub where students from all over the world would mingle, like they do at prestigious universities in the west. In fact, Harford himself is the only and perhaps the first ever American Ph.D. at his department, he added.

“In my class, I have just seen Ukrainians,” Harford said. “I’ve seen some Chinese and Indian students around but not many.”

The Ukrainians’ attitude to the odd American ranges from cautious suspicion to sometimes excessive excitement, he shared.

“Sometimes they may have somewhat unrealistic expectations,” he said. “They would like to have their American dream and have SpaceX here. But I think that having foreigners here and interacting with them, getting out to conferences in the West and sending their people to fellowships to the US and Europe, that’s part of overcoming some of that Soviet legacy.”

At a crossroads

Harford arrived in Ukraine in 2018, four years after Russia’s forced annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, a formerly Ukrainian territory on the Black Sea coast. It was also four years after the Euromaidan protests, which ousted the pro-Russian Ukrainian president Victor Yanukovich who was later accused of treason.

It was actually Yanukovich and his allies (connected to Russian oligarchs) that stalled the signing of the European Union’s Ukraine Association Agreement, which aimed to strengthen the connection between Ukraine and western Europe. Instead, they worked to reinforce Russia’s influence in Ukraine. The Euromaidan revolution swiveled Ukraine back toward the west.

Since than, Harford said, Russia has behaved like a “jealous ex-husband who rather murders the wife than lets her go”.

“I didn’t think about it that much while I was in the U.S., but after I got here, and over the course of several years, I discovered that this is really a very simple conflict,” Harford said. “For Ukraine, it makes things really complicated. It’s difficult to rise above the Soviet legacy, it’s almost impossible when they are actively waging war on you.”

Although the Crimean Crisis formally ended in March 2014, the war in Eastern Ukraine never stopped. From 2014 to the beginning of Putin’s full-scale invasion on Feb. 24, 14,000 people died in struggles with Russia-sponsored separatists in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, according to Crisis Group International. The conflict led to the tragic crash of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down by the pro-Russian rebels over Eastern Ukraine in July 2014 while en route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur.

Making history

Despite Russia’s intensifying aggression, Harford remains in Ukraine. Shortly before the beginning of the invasion (which as he says was by no means unexpected for the Ukrainians), he relocated with his family to the Zakarpattia region near Ukraine’s western borders.

“I thought I knew what patriotism was, and what freedom was, until I came here and saw how the Ukrainians act,” he said. “It’s not for glory, nor for payment. A lot of my colleagues were born and lived under the Soviet Union, and they understand what’s at stake. It’s very inspiring to see.”

It’s this Ukrainian resolve and courage that makes Harford believe not only in the future of Ukraine, but also in his future in the country.

After finishing his Ph.D., he sees himself launching a start-up developing active radiation shielding for spacecraft aiming for Mars and deep space, helping to rebuild the new, more modern Ukraine.

“Never in history have we had a chance like this,” he said. “To leave, I think I would regret it for the rest of my life.”

But the war is not over yet. Every day, reports keep coming from Ukraine about Russian missiles ravaging Ukrainian cities. The threat of a nuclear accident at one of the occupied power plants, or, even worse, the possible use of banned chemical weapons or even tactical nuclear missiles, hangs over Ukraine. The path to freedom is nowhere near secured.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPutlarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.