SpaceX’s trailblazing Polaris Dawn mission will soon begin its daring trek into Earth orbit — and with it, the plunge through the belt of radiation wrapped around our planet.

The four-person crew of civilians, led by billionaire entrepreneur Jared Isaacman, will lift off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida early on Tuesday (Sept. 10) after a series of launch delays attributed to technical issues and bad weather. Soon, the crew will attain a maximum height of 870 miles (1,400 kilometers) — three times the altitude of the International Space Station (ISS) and farther than any human has flown since the Apollo era over 50 years ago.

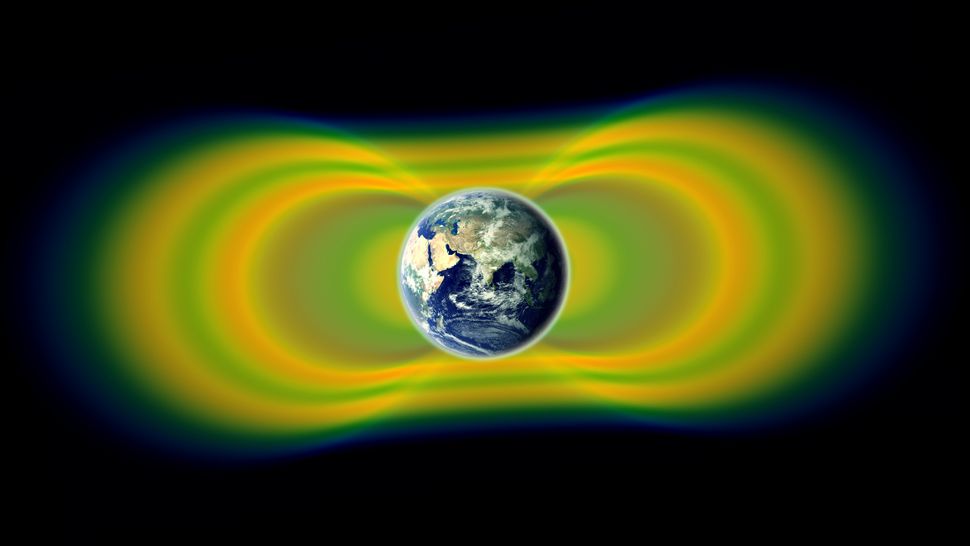

Over the course of five days as it flies at this record altitude, the SpaceX Dragon Resilience capsule carrying the crewmembers will pass through the inner Van Allen radiation belt, one of two donut-shaped swaths of highly energetic particles from the sun that are magnetically trapped around Earth. The belts, which shield our planet and its atmosphere from billions of such fast-moving particles, are the strongest over the equator and effectively non-existent over the poles.

Astronauts who embark on longer and farther missions — Mars, for instance — must safely pass through these belts to reach outer space, so the mission is “a unique opportunity to perform research in an increased radiation environment,” Dr. Emmanuel Urquieta, the vice chair for aerospace medicine at the University of Central Florida’s College of Medicine, told Space.com in a recent interview.

Isaacman and his crewmates — former U.S. Air Force pilot Scott “Kidd” Poteet and SpaceX engineers Sarah Gillis and Anna Menon — will also attempt the first private spacewalk at an altitude of 435 miles (700 kilometers). During the historic spacewalk, the crew will be within the safety of the inner radiation belt, which begins at roughly 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) from the surface.

Unlike previous spaceflight missions that have often differed in their research goals, Polaris Dawn carries a radiation monitoring device similar to the one currently onboard the ISS. The device, which is among 40 onboard science experiments, will allow scientists to catalog radiation levels in a consistent and systematic way, Dr. Urquieta said. “You can then compare apples to apples on radiation.”

The SpaceX crew capsule has undergone rigorous testing to ensure its avionics don’t fry from the harsh radiation, which would otherwise deprive the crewmembers of crucial navigation and communication capabilities. While the SpaceX team tested the limits of avionics components by barreling radiation onto them until they broke, the upcoming plunges will test that capability real-time, providing the data useful to advance technology such as spacesuits and life-support instruments that will be necessary for longer crewed missions in the future.

Scientists also plan to look for any biological effects caused by radiation by comparing the crewmembers’ health before and after flight, which would then be valuable in crafting effective countermeasures and personalizing medicine for astronauts on future missions, Dr. Urquieta said.

Compared to clinical trials on ground where typically thousands of participants are monitored, just about 700 astronauts have flown into space since the 1960s, and the vast majority of them have been males.

The Polaris Dawn crew comprises two men and two women, presenting a valuable opportunity to assess whether any effects of spaceflight, including those from radiation, can be attributed to the biological sex of the astronaut, Dr. Urquieta said.

“We still don’t have that diverse population that we’d like to have in human spaceflight,” he added. Private spaceflight missions like Polaris Dawn “start to provide us with information that otherwise we wouldn’t have.”