SpaceX will boost the space station for the first time Friday (Nov. 8), as the company prepares to eventually kill the orbiting complex.

A Dragon cargo spacecraft docked to the International Space Station (ISS) will fire its engines for 12.5 minutes on Friday (Nov. 8), NASA officials said at a press conference Monday (Nov. 4). Other spacecraft have done this before, but it will be a first for a SpaceX capsule — and an important precursor to a bigger Dragon vehicle that will one day drive the ISS to its demise.

“The data that we’re going to collect from this reboost and attitude control demonstration will be very helpful … and this data is going to lead to future capability, mainly the U.S deorbit vehicle,” Jared Metter, director of flight reliability at SpaceX, told reporters at the livestreamed teleconference.

Related: FAA clears SpaceX to resume Falcon 9 rocket launches

In July, SpaceX was tasked as the company to deorbit the ISS no earlier than 2030, once new commercial space stations are ready to step in for the ageing complex. SpaceX will use a monster Dragon for the effort, so the planned ISS reboost using the current generation of Dragon will be useful.

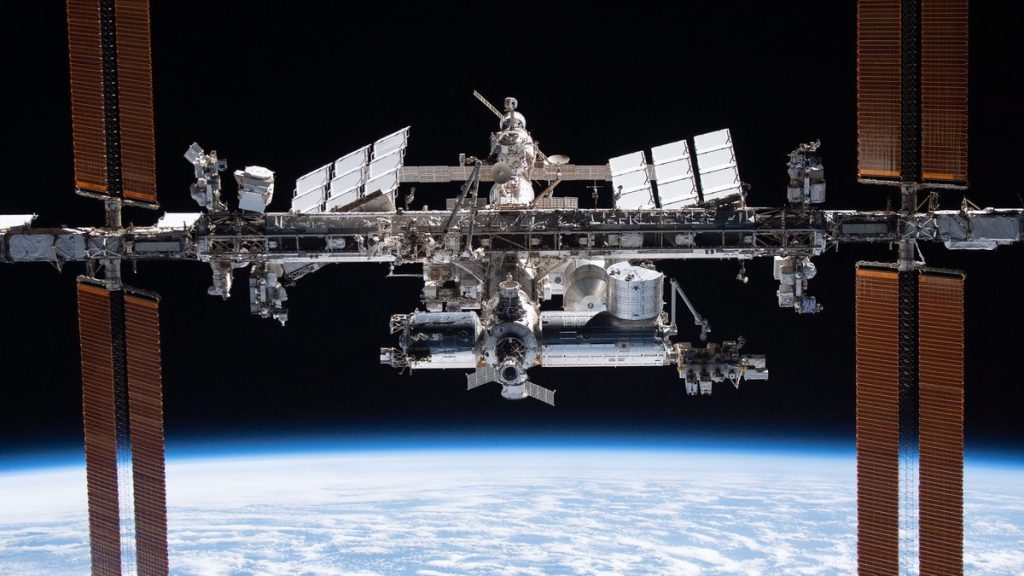

The ISS is in low Earth orbit, roughly 250 miles (400 km) above our planet. Stray molecules of Earth’s atmosphere combine to drag the six-bedroom complex down over time, making it necessary to use spacecraft to “reboost” or push the space station to a higher altitude.

Traditionally, Russian Soyuz spacecraft have fulfilled that reboost capability, but things are changing rapidly. Russia remains a partner in the ISS after its unsanctioned invasion of Ukraine in 2022; even though most other international space agreements ruptured, the ISS is a policy project and cannot operate as independent bits, NASA has emphasized.

Russia plans to forge ahead with its own space station no earlier than 2028, which so far is before the rest of the ISS partnership’s commitments cease in 2030. Should Russia pull away, this means that other vehicles will need to step in for Soyuz. NASA already tested boosting with a Northrop Grumman Cygnus cargo craft in 2022. Now it’s SpaceX’s turn.

“It’s a good demonstration,” Metter said of the reboost. He did not immediately have the expected delta v, or the impulse per unit of spacecraft mass that the maneuver would impart, but emphasized the duration would be enough to “gather a lot of data” for the U.S. deorbit vehicle.

SpaceX’s historic push of the ISS will take place in the wake of several company hardware issues, which NASA and the company say are unrelated. These have led to problems during Falcon 9 rocket launches and landings, along with a Dragon splashdown, in recent weeks. All problems were resolved quickly with no impact to crew or public safety, and NASA officials expressed confidence in SpaceX’s capabilities after working alongside the company to scrutinize its performance.

“We work very closely with SpaceX on everything that we do relative to these Dragon launches. They share data with us very freely, and we work through all the issues jointly,” Bill Spetch, operations and integration manager of NASA’s ISS program, told reporters at the Monday teleconference. “We obviously always maintain a top priority on the safety of the vehicles coming to ISS, and so that really hasn’t changed for us,” he added.

The Falcon 9 rocket, which is the most prolific and successful booster in history, had three launch issues between mid-July and late September. The first issue on July 11 saw 20 SpaceX Starlink Internet satellites lost after an upper-stage propellant leak. Falcon 9 returned to flight two weeks later after the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which oversees regulatory activities in launches, approved SpaceX’s plan.

On Aug. 28, Falcon 9 experienced a second issue; its first stage did not land as designed after a Starlink launch that was otherwise successful. SpaceX returned to flight three days later, but on Sept. 28, Falcon 9 was grounded for a third time after an upper stage issue when it was launching the Crew-9 astronaut ISS mission for NASA.

The rocket was once again kept on Earth for two weeks, save for an FAA-granted exception to launch Europe’s Hera asteroid-inspection probe on Oct. 7. Falcon 9 returned to flight Oct. 11 and has launched successfully several times in recent weeks.

“We investigated each one of these anomalies independently, but then also looked at any crossover that could have occurred,” Metter said. “We identified no crossover, no common theme or systemic issue, common to any of these anomalies.”

The independent Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel for NASA, however, expressed concern with these incidents along with a slight problem during splashdown of Crew Dragon — a human-rated version of Dragon — with the four Crew-8 astronauts on Oct. 25, according to SpaceNews. The parachutes and drogues had slight timing anomalies that had no apparent adverse effect on the crew’s return.

One Crew-8 NASA astronaut had an undisclosed health issue after splashdown that landed them in hospital overnight; they were released the following day. NASA emphasized that the splashdown was otherwise “nominal” from an engineering perspective. NASA also has not drawn any links between the medical incident and Dragon’s performance.

The safety panel nevertheless said that spaceflight requires constant vigilance to ensure astronaut and mission safety and urged that neither NASA nor SpaceX let up their monitoring practices.

“When you look at these recent incidents over the last handful of weeks, it does lead one [to] say that it’s apparent that operating safely requires significant attention to detail as hardware ages and the pace of operations increases,” Kent Rominger, a former space shuttle astronaut who serves on the panel, said at a telephone meeting Oct. 31 attended by SpaceNews.

“Both NASA and SpaceX need to maintain focus on safe Crew Dragon operations and not take any ‘normal’ operations for granted,” added Rominger, but neither he nor other panel members offered specific recommendations or remedies.