The Starlink v1.0 Launch 12 mission (the 13th overall flight of Starlink) is set for another launch attempt on Monday September 28th at 10:22am EDT (14:22 UTC) from LC-39A at Kennedy Space Center. The weather forecast issued the day before launch shows a 60% chance of favorable weather with the primary concerns being the thick cloud layer and cumulus cloud rules.

There is no backup day currently scheduled as two government payloads are — as of publication — slated to launch on Tuesday, September 29th. If the Starlink launch does not take place on Monday, it may need to wait for the range to become available again.

A previous attempt on September 17th was called off due to a “recovery issue” before rough weather in the Atlantic from a passing hurricane led the recovery ships to return to port. After initially setting a new attempt for the 27th, a further slip was announced after the NROL-44 launch at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station needed to slightly delay its flight.

Overall, it was an eventful first attempt for the SpaceX fleet. After fairing catcher ships Ms. Chief and Ms. Tree left for the recovery zone, Ms. Tree diverted to the port at Morehead City, NC, where it stayed while the other ships went to the recovery area and then returned home to Port Canaveral.

Tug Finn Falgout spent several days towing the drone ship Just Read the Instructions (JRTI) back to Port, arriving on September 22nd before leaving again the next day with the other landing ship, Of Course I Still Love You (OCISLY), to the recovery area.

JRTI had just returned to action after sister ship OCISLY handled the previous three missions. JRTI began east coast service in June after undergoing extensive upgrades, then took a break of close to two months.

Support ship GO Quest is also helping with the recovery operations.

Starlink v1.0 L6 launch. Photo by Julia Bergeron.

The SpaceX fleet is also due for an internet upgrade in the near future as the company has filed for a permit to test the nautical version of their Starlink user terminal on up to 10 ships, including the drone ships and their support vessels.

The payload for this flight will be another batch of 60 satellites for the constellation of SpaceX Starlink satellites to provide high speed internet service. With each of these satellites having a mass of about 260kg, the full payload stack masses nearly 16 metric tons. According to pre-launch data released on Celestrak, the targeted deployment orbit will be approximately 260x280km.

The launch vehicle will be using first stage 1058.3, a lightly used booster that previously lofted the Commercial Crew DM-2 mission and the ANASIS-II satellite for the Korean government. One of the fairing halves was previously used on the Starlink v0.9 and Starlink v1.0 L5 missions.

Upcoming flights for SpaceX include the GPS III SV04 mission for the U.S. Space Force at 21:55 EDT local time on September 29th (01:55 UTC on 30 September), followed by another Starlink launch in October. Other Starlink missions will occur later in the year as they can be fit around a busy stretch of missions for outside customers.

Non-Starlink missions known for the rest of the year include the Crew 1 flight of Dragon with four astronauts on October 23rd, SXM-7 for Sirius XM in early November, the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite for NASA and ESA from Vandenberg on November 10th, cargo Dragon SpX-21 for NASA in mid-November, Türksat 5A at the end of November, and SpaceX’s Transporter-1 dedicated rideshare in mid-December.

SpaceX appears to be on pace for around 25-28 launches in 2020. While this is about ten less than the ambitious goal mentioned by company president Gwynne Shotwell last December, it would still easily break the company record of 21 launches in a calendar year.

SpaceX presentation to FCC, September 2020

Meanwhile, SpaceX continues to make progress with the deployment and operation of the Starlink constellation. During the webcast of their last mission and in recent presentations to the FCC, SpaceX said they have achieved 100Mbps download speeds with sub-40ms latency in their private beta phase of Starlink testing.

It was also announced that they have launched and tested two satellites with laser inter-satellite links, a feature that will eventually be added to the entire constellation. Public beta testing is still expected to open before the end of the year.

Webcast host and SpaceX engineer Kate Tice noted that “our network of course is very much a work in progress, and over time we will continue to add features to unlock the full capability of that network.” SpaceX is doing an enormous amount of development in-house, from the satellites to the ground stations to the antennas for the user terminals. Doing so much of the work themselves will allow SpaceX to have tight control over the costs of building out the constellation as they continue to iterate on the designs and improve performance.

The timing of these performance revelations may be linked to SpaceX’s desire to participate in the FCC’s Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF) auction in late-October, which will allocate $16B over the next decade to subsidize internet service to poorly served areas in the United States. In setting up the rules for the auction, the FCC has expressed some skepticism of allowing new technologies such as LEO internet constellations to win funding for higher tiers of performance.

While SpaceX continues working with the FCC on plans to serve the U.S. market, they are also busy pursuing the opportunity to offer service in other countries. Filings have been seen in Canada and Australia as SpaceX works through the process of gaining permission to serve those markets. Some of the initial filings are being done through their TIBRO subsidiary and various national entities they have set up under that umbrella.

Animation by Ben Craddock for NASASpaceflight showing the movements of Starlink satellites into their orbital planes since August 1, 2020. The satellites from each launch split into three groups that each form a plane.

Having now filled 18 evenly spaced planes in the constellation, SpaceX should be attaining continuous coverage in the northern U.S. and southern Canada areas where they intend to launch the Starlink service. That 18th plane consisted of satellites from the v1.0 L9 mission, with some satellites from previous launches being used to fill in between existing planes. There will eventually be 72 planes of 22 satellites each in the initial shell of the Starlink constellation.

In the lower right portion of the animation, the deorbiting of the v0.9 test satellites can be seen. So far, 32 satellites from that first test launch of Starlinks have been deorbited, with more on the way. These early satellites lack part of the communications payload needed for full operation.

For launch, the final stages of preparation will commence at the T-38 minute mark when the Launch Director determines that the vehicle is ready for propellant loading. When the “go” is given, chilled RP-1 fuel will flow into both stages of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle at 35 minutes to liftoff, along with liquid oxygen (LOX) loading into the first stage. LOX loading onto Falcon 9’s second stage starts at T-16 minutes.

At T-7 minutes prior to liftoff, the liquid oxygen pre-valves on the nine Merlin-1D first stage engines open, allowing LOX to flow through the engine plumbing and thermally condition the turbopumps for ignition. This process is known as “engine chill”, and is used to prevent thermal shock that could damage the engines upon startup.

At the T-1 minute mark, the Falcon 9’s onboard flight computers run through final checks of the vehicle’s systems and finalize tank pressurization before flight. The launch director gives a final “go” for launch at T-45 seconds.

The nine Merlin-1D engines on the first stage ignite at T-3 seconds, with liftoff taking place at T-0 following a quick final check by the onboard computers to verify that all systems are operating nominally.

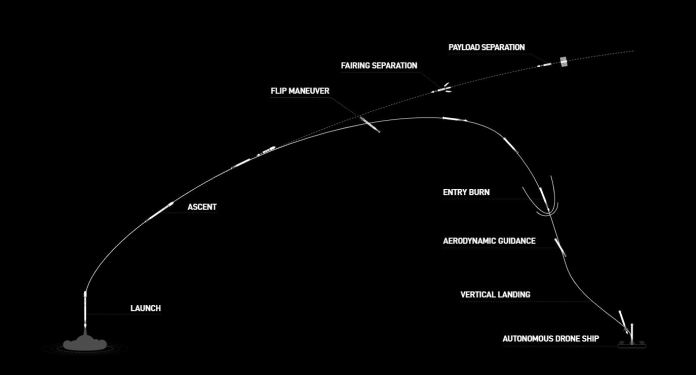

Falcon 9 flight activities. Graphic by SpaceX.

After lifting off from LC-39A, the Falcon 9 pitches downrange as it accelerates towards orbital velocity. At around a minute and 12 seconds into the flight, the vehicle passes through the region of maximum aerodynamic pressure, or “Max-Q”. During this portion of flight, the mechanical stresses on the rocket and payload are at their highest.

The nine Merlin-1D engines on Falcon 9’s first stage will continue to burn until around T+2 minutes and 32 seconds, at which point they shut down in an event known as MECO, or Main Engine Cutoff. Stage separation occurs shortly afterward, with second stage Merlin Vacuum engine ignition taking place at the T+2 minute 43 second mark. Upon engine startup, the second stage will continue to carry all 60 satellites to a low Earth orbit, with an inclination of 53 degrees.

The 5-meter payload fairing housing the payload during the initial phases of launch will separate at 3 minutes and 22 seconds into the flight. The fairing halves will fall back to Earth and descend under parafoils, landing about 45 minutes after launch to be recovered by the waiting ships.

While Falcon 9’s second stage and payload continue towards orbit, the first stage will perform an entry burn which ends at 6 minutes and 40 seconds into the flight, in order to slow its descent and refine its trajectory to the droneship. A final landing burn will begin shortly before the booster touches down on the deck of JRTI approximately 8 minutes and 24 seconds after liftoff, approximately 630km downrange from the launch site.

The Merlin Vacuum engine on Falcon 9’s second stage shuts down for the first time at 8 minutes and 48 seconds into the flight in an event known as SECO-1, or Second Engine Cutoff. After coasting for a bit more than half an hour, the second stage will reignite at the T+42:26 mark for a three second burn to raise the perigee into a more circular orbit.

Just over an hour into flight, the group of Starlink satellites will float away from the second stage when the tension rods holding them together are released at T+01:01:24.

The second stage is expected to light its engine one more time for a deorbit burn, splashing down in the ocean west or south of Australia on its second orbit.

– Advertisement –