A number of spacecraft are staring directly into the sun. And for good reason.

Space agencies, scientists, and nations want to better understand our stormy sun, a glowing sphere of gas that’s capable of energetic explosions from its surface. A common such event is a solar flare, which is an explosion that emits light and energy into space, sometimes towards Earth. You might hear more about such solar events in the coming years as the sun’s activity ramps up — but rest assured its normal, natural behavior from your local, medium-sized star. Fortunately, Earth shields us from potential harm, though our power grids and communications can be severely damaged.

Similar to storm seasons or climate patterns on Earth, the sun experiences a cycle of weather. The sun’s lasts for 11 years. During this pattern, solar activity increases for some 5.5 years, then decreases, then picks up again.

“It’s the space equivalent of hurricane season. We’re coming into another one,” Mark Miesch, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Space Weather Prediction Center, told Mashable.

In this current cycle, solar activity will peak around July 2025(Opens in a new tab) (aka the “solar maximum”). So expect some fireworks. For example, NOAA recently reported(Opens in a new tab) that on Feb. 17 the “sun released a strong #SolarFlare,” resulting in some temporary radio blackouts. Crucially, people standing on Earth were not at risk. In the coming years you may see some sensationalized scaremongering on the internet about incoming solar flares. Yes, there is potential for damage to telecommunications. That’s why watching the sun and preparing for potential impacts is vital. But civilization will not end.

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

“Humans have been on Earth for several million years,” noted Miesch. “It’s not like a big solar flare is going to knock everyone out tomorrow.”

How scientists know about the solar cycle

Scientists have a strong grasp of the 11-year solar cycle. Centuries of observations show the sun has cycled like this for at least some 400 years(Opens in a new tab). In the 1800s, the German astronomer Heinrich Schwabe used a telescope to view the sun almost every day for a whopping 42 years(Opens in a new tab). He saw bounties of sunspots, which are cooler spots on the sun’s surface that increase as solar activity ramps up. Schwabe watched and drew the sunspots that appeared and grew on the sun’s surface, providing especially clear evidence of the 11-year cycle.

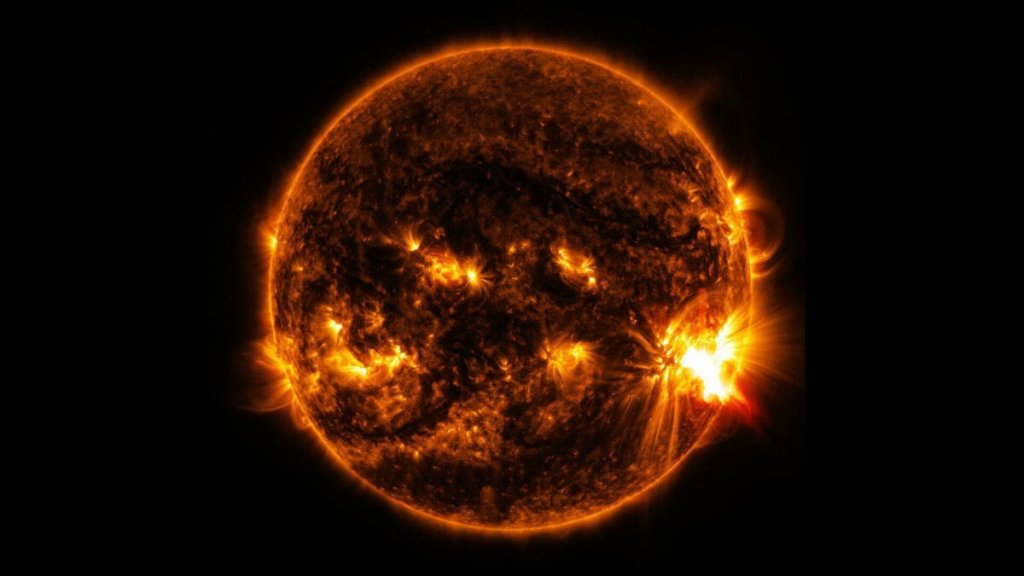

Today, we’re in Solar Cycle 25, which began in 2019 when solar activity (sunspots, solar flares, and beyond) quieted, called the “solar minimum.” The difference between the minimum and maximum is significant, as the NASA graphic below shows:

Credit: NASA / SDO

Today, solar scientists use satellites and spacecraft to monitor the sun’s dynamic behavior. For example, the Solar Ultraviolet Imager(Opens in a new tab) aboard a NOAA weather satellite continuously watches for solar activity, and NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory seeks to better understand the sun’s fickle weather, and how such violent solar eruptions impact Earth.

How solar flares impact Earth and people

Solar flares can impact Earth when the emanated light particles hit our planet. It’s a type of space weather that NOAA, NASA, and other agencies aim to better grasp and forecast. But it’s not the only type of potentially problematic space weather. Here are three main solar explosions that can affect Earth:

-

Solar flares: Explosions of light from the sun’s surface. Driven by the behavior of the sun’s magnetic field, they expel extreme amounts of energy (visible light, X-rays, and beyond) into space.

-

Coronal mass ejections (CMEs): These occur when the sun ejects a mass of super hot gas (plasma). “It’s like scooping up a piece of the sun and ejecting it into space,” NOAA’s Miesch explained. Sometimes solar flares trigger CMEs, and sometimes they don’t.

-

Solar energetic particle (SEP) events: These are essentially solar flares with lots of energetic particles. They’re especially dangerous to astronauts and satellites.

The big question is how different types of flares and radiation impact our lives. Fortunately, life on Earth is shielded from such particles and radiation. Our atmosphere protects us from things like X-rays and energetic particles emitted from the sun. Meanwhile, Earth’s potent magnetic field (generated by Earth’s metallic core) deflects many particles from solar storms and shields us from the sun’s relentless solar wind, a continuous flow of particles (electrons and protons) from our star.

Yet Earth, and our modern technology, are still impacted by these solar events. Some impacts happen to be glorious. Some are potentially damaging to our infrastructure. The glorious result is the Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights. Solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and other space weather cause these vivid “dancing light” sky events. When solar particles hit Earth, some are trapped by the planet’s magnetic field, where they travel to the poles and collide with the molecules and particles in our atmosphere. During this collision, these atmospheric particles heat up and glow.

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

But a spectrum of potential hazards, ranging in seriousness from briefly problematic to extremely damaging, can ensue when the likes of a strong solar flare or CME hits Earth.

The strong solar flare that hit Earth on Feb. 17 resulted in just temporary radio blackouts in some areas. NOAA rated the “STRONG Radio Blackout event”(Opens in a new tab) with a Radio Blackout rating of 3 out of 5. Sure, the burst of radiation from the sun was powerful. But around 175 such events occur during each solar cycle, according to NOAA(Opens in a new tab).

Things can grow more serious, however, when a strong CME impacts Earth. Ultimately, such a solar storm can induce intense currents in our power grids, among other deleterious impacts to satellites. Infamously, a potent CME in 1989 knocked out power to millions in Québec, Canada. The CME hit Earth’s magnetic field on March 12 of that year, and then, wrote NASA astronomer Sten Odenwald(Opens in a new tab), “Just after 2:44 a.m. on March 13, the currents found a weakness in the electrical power grid of Quebec. In less than two minutes, the entire Quebec power grid lost power. During the 12-hour blackout that followed, millions of people suddenly found themselves in dark office buildings and underground pedestrian tunnels, and in stalled elevators.” Scary, indeed.

“It’s not something to lose sleep about, but it’s something to take seriously.”

That’s why agencies like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center vigilantly observe the sun(Opens in a new tab) with advanced satellite instruments. They can tell us what’s happening on the sun, and what’s coming, allowing us to prepare. If necessary, for example, power utilities could temporarily shut off power to avoid conducting a power surge from a CME. As solar cycle activity ramps up, most solar events won’t be damaging or harmful. But one day again, an event could be.

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

“It’s not something to lose sleep about, but it’s something to take seriously,” emphasized Miesch.

And for the extreme minority of us who spend time in space — including the astronauts who will ride aboard looming expeditions to the moon — watching space weather is especially critical. A solar energetic particle (SEP) event would be particularly hazardous to astronauts, who would be exposed to unsafe levels of radiation. Space agencies are experimenting with shielding(Opens in a new tab) for such occurrences, especially during long, deep space journeys to locales like Mars.

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

How to prepare for a powerful solar storm

Good news: If there’s potential for a powerful burst of radiation, or one is headed our way, credible government agencies like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center or the National Weather Service will inform us. (I suggest avoiding online tabloids for space weather information, because they warn of an apocalyptic solar storm every other week or so 🙄.) A “Watch” is issued “when the risk of a potentially hazardous space weather event has increased significantly, but its occurrence or timing is still uncertain,” the National Weather Service notes(Opens in a new tab). These would be followed, if necessary, by escalating “Warnings” or “Alerts.”

The National Weather Service also has guidance on how to prepare for an extreme solar storm(Opens in a new tab). It reads like a hurricane or earthquake kit, with an emphasis on back-up power.

This story has been updated with more information about solar flares.