The total solar eclipse on April 8, 2024, will be a historic event that many across the United States will want to be part of. However, if the weather does not cooperate during those few minutes you get in each location in the path of totality, it could bring quite the anxiety and disappointment for those spending time, money, and resources to have the best experience.

That’s why all eyes are on any and all information to determine the weather forecast to prepare as early as possible where the best location might be to have the best chance at clear skies, and for event organizers, to have a backup plan if skies turn cloudy and stormy.

The map above is all over the internet, showing the cloud climatology (or the study of climate) over the past 28 years compiled from data from Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES). While this image indicates that certain areas like Texas have historically had much clearer skies versus parts of the Northeast, there remains uncertainty of what could happen this year, which will depend on what types of weather systems develop and will be moving across the country days and even weeks leading up to the main event.

Related: What will it be like to experience the total solar eclipse 2024?

As a meteorologist myself, I can tell you that for others both in the broadcasting field and working for weather forecast agencies such as the National Weather Service, compiling a forecast (especially for big events like this) is no easy task.

We have to take several things into consideration the closer we get to April 8 using numerical weather prediction models (both short and long term), satellite and radar data, and on the day of, weather observations as they come in.

Yes, climatology is important too, but as I mentioned above, there are no guarantees one year will be exactly like a previous one or stick to the average — remember, like an average of numbers, it takes many different ones both high and low to come to that middle ground summary.

So, to give us an even better perspective on what goes into climate studies and how forecasts will continue to gain more accuracy the closer we get to the eclipse, we spoke with Canadian Meteorologist Jay Anderson, (who’s also a passionate eclipse chaser) with 40 years of experience both with weather forecasting and seeing eclipses in all types of scenarios.

Jay Anderson is a meteorologist with over 40 years of experience both with weather forecasting and chasing eclipses. He owns and runs Eclipsophile.com, a one-stop-shop for anyone looking for climate and weather information that coincides with celestial events such as solar eclipses, auroras, planetary transits, comets, and occultations.

Space.Com: Jay, for those us of with experience in the field of forecasting, we are used to the process of what goes into trying to figure out what Mother Nature has in store. But for the average reader, there’s so much to learn and know. I’d like to start by referencing your site, Eclipsophile, where you’ve put together information anyone can access that combines factual data and statistics paired with your experience.

Jay Anderson: Someone traveling to the eclipse is going to want weather information a long way ahead and that’s what the material on my Eclipsophile website attempts to answer. It tells them where to head for the best chances, but, of course, doesn’t guarantee them the eclipse — that has to come later, in the days before the shadow comes by, when they turn to forecasts.

For someone staying at home, climatology has relatively little value. Instead, the local forecasts will lead them to a viewing spot if they are enthusiastic enough to want to leave home for a short journey.

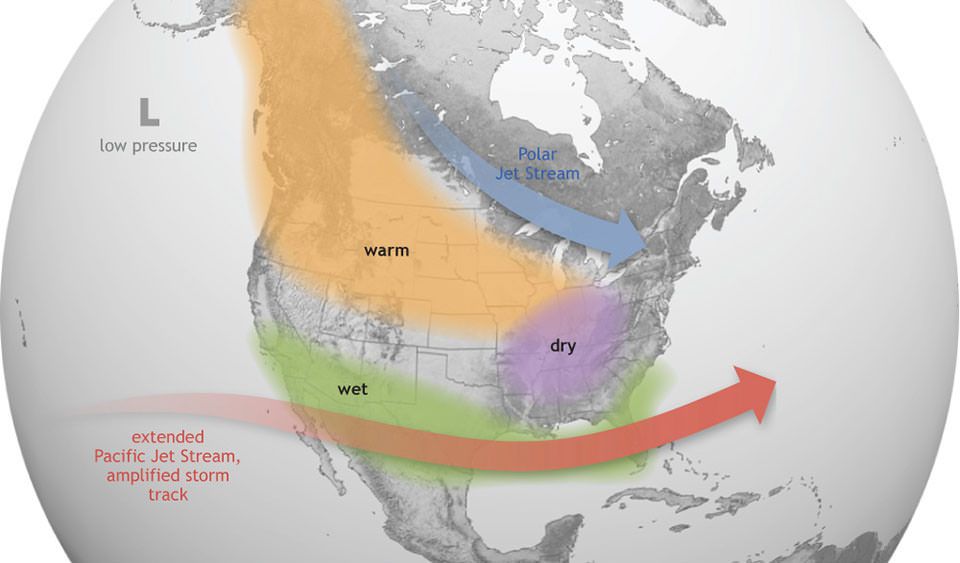

Space.Com: So where we are at right now, we take the focus to climatology as we still are days away from when many computer models start to produce data for long-range forecasts. There’s been talk that this is an “El Nino” year that might have some impacts.

Anderson: The impact of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is something that comes up for nearly every eclipse, but particularly for this one which comes at the end of an El Nino winter. I was not expecting the strong signal that appeared when I examined the effects of Pacific warming on eclipse-track cloud cover, but it’s since been backed up by another investigation and by other datasets.

El Nino brings a sunnier than average spring to Mexico, Texas, Arkansas and parts of other states in the middle of the track, but does little for places farther north when compared to neutral ENSO conditions. However, the impact of El Nino is still a climate statistic, one of several, and will be superseded by numerical forecasts in a few more days. I completed a map of February cloudiness to see how the spring has been evolving and it turns out the month has been quite a bit sunnier than normal along the track. It is reassuring, but what it means for eclipse day is up in the air.

Space.Com: What about the topography of the areas in the path of totality as well as what season we are in? Will that make a difference?

Anderson: In this eclipse, it makes a difference. The Gulf Coastal Plain in Texas and the lowlands along the Mississippi are highways for cloud and moisture spreading northward from the Gulf of Mexico. However, the flow comes up against the Balcones Escarpment in Texas Hill Country, which is high enough to block the shallower moisture intrusions.

Farther north, the lowlands from North Texas to Missouri are well known for fog and low clouds, and here again, the higher terrain on the west side of the track often remains clear when the lowlands are socked in. It all adds up to about 10-15 percent less cloud on the west side of the track compared to the east.

Farther north, the springtime climatology is so cloudy that terrain doesn’t make much difference until you get past the Great Lakes and into the Appalachians. One bright spot is along the shores of Lakes Erie and Ontario, where sunshine is a little more abundant because the flow off of the lakes suppresses convection for a short distance inland. It takes just the right weather pattern to make this work, but Cleveland, Erie, and Rochester reap the benefits when it happens.

Space.Com: Let’s say we do have some clouds during totality and leading up to it. Can you still see the eclipse occurring or is there a point of no return we could get to with too many clouds?

Anderson: I’ve seen more than a few of my 25 eclipses through cirrus clouds and one through heavy overcast (in China, with a break at the right moment). Cirrus is going to be the major problem in Mexico and also in Texas, brought in by the sub-tropical jet. Because of the China experience, I’m not ready to write off any amount of cloud cover, but you’ve got to be lucky. A big comma-cloud system over the Northeast States with a cold front to Texas would leave a lot of folks disappointed. Cumulus will disappear as the shadow brings cooler temperatures; thunderstorms will not — they hardly even notice an eclipse. Fortunately, there are usually clear skies somewhere nearby when thunderstorms are present.

Space.Com: All right, so based on everything we’ve talked about and you studied, where do you feel will be the best place to view the April total solar eclipse?

Anderson: Mazatlan and the interior Mexican Plateau have the best climatology. I’m going to be in Torreon, near the point of maximum eclipse. In the U.S., crowd up against the Mexican border on the west side of the shadow path. In Canada, try Prince Edward Island or the area around Kingston or Niagara Falls. Better yet, watch the forecast two days before and then pick. I guarantee that some areas expected to be cloudy will be clear and some of those expected to be clear will be cloudy.

Space.Com: As we move into the end of March, we will start to get data from the longer-range forecast models and then the closer and closer we get, the more fine-tuned the weather forecasts will be. Let’s go over that timeline.

Anderson: There are many levels of sophistication in the use of computer models. To storm chasers, they are second nature, for others, a bit of a mystery as they’ve probably never encountered them before. I point people to the raw numerical output so that they can look at a couple of models to see where there is agreement and disagreement. When we get to within four or five days of the eclipse, those models will be giving a more reliable signal that can be used for advanced planning.

Two days out, they can be used to select a final site [to watch the eclipse] if they are willing to travel to a sunny spot. For the casual eclipse watcher at short notice, the local TV forecast will do. In short, use climatology for another 10 days or so if you’re determined to see this thing, and then gradually switch to the models after April 3 (but peek at them beforehand if curiosity gets the better of you).

Space.Com: Thank you Jay! Any final advice or thoughts?

Anderson: Move early to get into place — at least a day beforehand. When eclipse day is here and you leave home to find a sunny spot, use the satellite images online or on TV. There will be millions of others doing much the same. To me, eclipses are all about travel, and I have that luxury in my retirement.

There won’t be another in the Lower 48 until the 2040s, so grab this opportunity while you can. Share it with family, and someday in the future, your grandkids will talk about sharing this eclipse with you as they share with theirs.