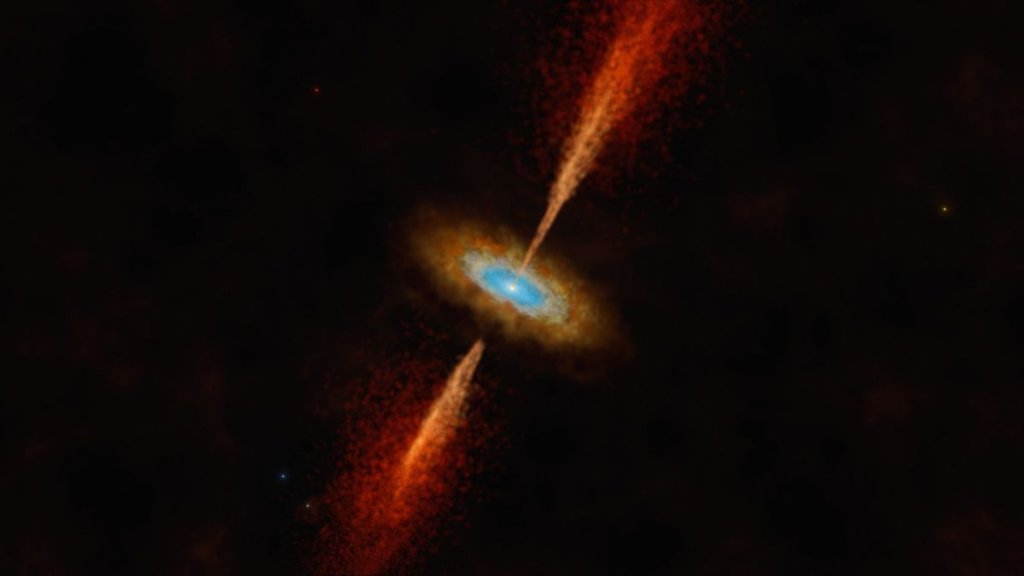

Astronomers have discovered the first example of a swirling disk of material feeding a young star located in a galaxy outside the Milky Way. The disk is near-identical to those found around infant stars in the Milky Way and suggests that stars and planets form in other galaxies just as they do in our own.

The young star in question is located in the Large Magellanic Cloud — a neighboring galaxy to the Milky Way located 160,000 light-years away — and its system, designated HH 1177, is embedded in a massive cloud of gas.

The team behind this discovery observed the system with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), the largest astronomical project on Earth consisting of 66 antennas in Northern Chile that make up a single radio telescope.

“When I first saw evidence for a rotating structure in the ALMA data, I could not believe that we had detected the first extragalactic accretion disc. It was a special moment,” researcher lead author and Durham University scientist Anna McLeod said in a statement. “We know discs are vital to forming stars and planets in our galaxy, and here, for the first time, we’re seeing direct evidence for this in another galaxy.”

Related: Black hole shreds star in a cosmic feeding frenzy that has astronomers thrilled

McLeod and colleagues were tipped off to the existence of this system when the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) spotted a jet emerging from a forming star. This instrument can make observations in the visible wavelength range while also measuring the wavelengths of light coming from an object, allowing scientists to tell what types of matter they’re looking at.

“We discovered a jet being launched from this young massive star, and its presence is a signpost for ongoing disc accretion,” McLeod added. To confirm an accretion disk was present in HH 1177, the scientists had to measure the movement of dense gas around the star.

Accretion disks in and outside the Milky Way

Accretion disks like this newly observed one form when matter falls toward an infant star or another accreting object like a black hole or neutron star. As the material falls onto these objects, it carries with it angular momentum (rotational spin), which means it can’t go directly to that central body. Instead, this matter forms a flattened spinning disk that gradually feeds matter to the central object.

The gas at the center of the accretion disc, closer to the central object — in this case, a young feeding star — moves faster than matter at the outskirts of the disk, and it is this variation in velocity that is the “smoking gun” that indicates the presence of an accretion disk.

“The frequency of light changes depending on how fast the gas emitting the light is moving towards or away from us,” team member and Liverpool John Moores University research fellow Jonathan Henshaw said. “This is precisely the same phenomenon that occurs when the pitch of an ambulance siren changes as it passes you, and the frequency of the sound goes from higher to lower.” (This phenomenon is known as redshift or blueshift, depending on whether the observed object is moving toward or away from Earth.)

Astronomers have spotted bright accretion disks around objects like supermassive black holes in other galaxies before due to their immense gravity generating violent conditions that cause gas and dust in these disks to glow brightly, often outshining the combined light of every star in the galaxy that surrounds them. Yet accretion disks around stars, from which planets eventually emerge, are much tougher to spot even within the Milky way, partially because young stars are often still cocooned in the gas and dust clouds from which they are born.

The situation is somewhat different in the Large Magellanic Cloud, as the material that is birthing young stars is less rich in dust. This means that HH 1177 has already escaped much of the “cocoon” from which it was born, allowing astronomers to observe its central star and possibly even watch the early stages of planet formation. Our own solar system would have been undergoing the same process around 4.5 billion years ago when a protoplanetary disk surrounded the young sun in the process of birthing the planets.

“We are in an era of rapid technological advancement when it comes to astronomical facilities,” McLeod says. “Being able to study how stars form at such incredible distances and in a different galaxy is very exciting.”

The team’s research is presented in a paper published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, Nov. 29.