Martian dust may have smothered NASA’s InSight lander to death, but the robot will always be remembered for unveiling many firsts about the Red Planet.

“The goal of the InSight mission was to rewrite the textbooks. We have done it, literally,” Bruce Banerdt, principal investigator of the InSight mission, said during a plenary talk on March 13 at the 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) held in Texas and online.

InSight, short for “Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport,” launched atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket in May 2018. Six months later, the three-legged, $814 million robot landed on a yawning patch of land near Mars’ equator called Elysium Planitia.

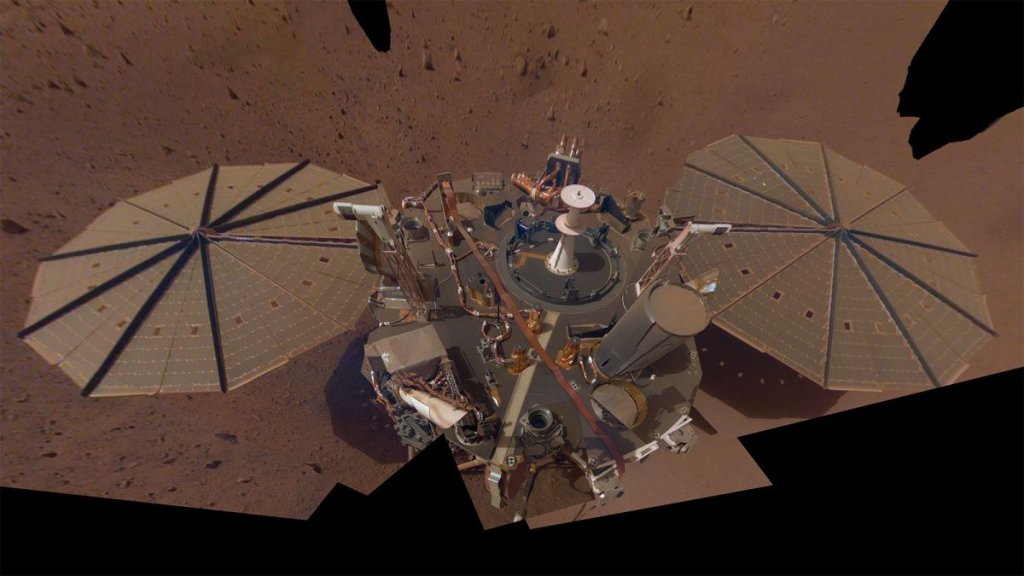

Related: NASA’s Mars InSight lander snaps dusty ‘final selfie’ as power dwindles

On the robot’s first Martian day, scientists used Frank Zappa’s “Dog Breath, In The Year Of The Plague” to awaken it, marking the first time a wakeup song was used for a spacecraft on another planet. During its four years of operations on Mars, the robot listened to the planet’s rumblings, detecting more than 1,000 marsquakes (opens in new tab), the details of which revealed unprecedented insights about the Red Planet’s interior. The lander’s data also allowed scientists to hear Martian winds and detect more than 20,000 dust devils.

After almost doubling its expected lifespan of two Earth years, InSight succumbed to dust accumulation on its solar panels, which robbed the spacecraft of energy and silenced it forever. After multiple unsuccessful attempts to reach the robot, NASA ended the InSight mission in December 2022.

“I feel like Insight has been successful beyond my wildest dreams and certainly beyond the dreams of a lot of people who thought it sounded like a pretty boring mission when it was selected, and understandably so,” Banerdt said.

He credited the mission’s outstanding success to the commitment of the InSight team. “I am really just a face of literally thousands of people who have put in their sweat, their emotional commitment to make this mission happen, both on the technical side and the scientific side.”

Unlike other Mars missions like Perseverance and Curiosity that have been assessing the planet’s habitability, InSight was the first surface mission dedicated to shedding light on the Martian interior — the size of its core, for example, and the thickness of its crust and mantle. On Earth, seismologists have already answered these questions, so the InSight mission was like a time machine in many ways, Banerdt said.

To help scientists better understand the interior of Mars, InSight had a fleet of instruments: a camera to capture the texture and color of Martian surface, a radiometer to narrow down on the sizes of surface grains, and a seismometer to feel marsquakes, among other tools.

“We have a lot of different sensors on this mission, none of which were designed to do geology by design,” Banerdt said. But when the data collected by all sensors is taken together, “you can really start to put together a pretty complete picture of what’s going on beneath the [Martian] surface.”

Related: What is Mars made of?

1st quake on another planet — and then 1,322 more

The stationary lander felt its first marsquake on its 128th Martian day, April 6, 2019. It was a small quake close to InSight’s location and revealed the Red Planet to be seismologically active.

Most scientists think Mars does not have active plate tectonics like Earth does, so spotting marsquakes meant there are other processes involved, such as asteroid impacts or underground pressure buildup due to magma movement cracking the planet’s surface.

“We were really hungry at that point, because the seismometer had been on the ground for three months at that point and we hadn’t seen a single thing,” Banerdt said at LPSC. “And I was starting to not answer phone calls from NASA,” he joked.

The team later found that the initial three months were the noisiest part of the Martian year, and that the weather-driven winds were drowning out quakes that InSight would have otherwise heard. After those initial three to four months, InSight began detecting more and more marsquakes, including its most intense quake, of magnitude 4.7, on May 4, 2022, whose aftereffects lasted a record 10 hours.

“This actually was the largest marsquake that we saw in the entire mission,” Banerdt said, adding that the team was “extremely lucky” to detect the quake as it happened just before the spacecraft was being shut off to save power. The May 2022 marsquake was so massive that it saturated InSight’s seismometer and provided as much information as most other quakes combined, he said.

Using data gathered by the seismometer onboard InSight, scientists calculated the thickness of Mars’ crust to be about 25 miles (40 kilometers) directly below the lander and about 34 miles (55 km) for the rest of the planet. The team was also able to estimate the size of Mars’ core to be a little over 2,200 miles (3600 km), “which is quite a bit bigger than we expected,” Banerdt said.

Among its many firsts, InSight also detected the seismic waves created when four space rocks crashed into the Red Planet a few hundreds of kilometers from the robot. “Two of the largest [seismic] events on Mars are actually impact events,” he said. Because seismic waves record how much the planet reverberates after each impact as it happens, scientists got a front-row seat to understand how craters form on Mars in real time.

Marsquakes are mysteriously clustered in Cerberus Fossae

During InSight’s four-year long stay on Mars, scientists got a pretty good estimate of the seismic activity happening on the planet’s near side, or eastern hemisphere, which they had access to.

Scientists also found that the Cerberus Fossae region, which is about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from InSight, hosted more marsquakes than any other region scanned by the spacecraft. In its first year on Mars, the robot detected just a couple of large marsquakes, but it saw a dozen big ones in its second year.

While scientists say that Mars is about 1,000 times less seismically active than Earth, half the seismic energy for the entire Red Planet comes from the small Cerberus Fossae region. The explanation for that is still a mystery.

“Mars is unusual in the fact that we don’t really understand the statistics yet,” Banerdt said at LPSC. “[They] are a lot less straightforward than I thought they were.”

Unlike Earth, Mars lacks an inner core

Earth has a liquid outer core and a solid inner core, but scientists studying InSight data found that the same does not hold true for Mars.

Although the temperature at Mars’ liquid core is relatively low, it is not cool enough to solidify because the planet’s structure makes it difficult to drive convection, which would otherwise dissipate heat at the planet’s center and form an inner core like Earth did.

“Everything that we see is pointing to an inner core being extremely unlikely,” Banerdt said.

Related: Mars missions: A brief history

More discoveries ‘for decades to come’ from InSight data

InSight completed most of its requirements in the first two years of operation, so the mission was a success, even though one of its secondary efforts did not go according to plan.

One of the instruments onboard InSight, the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package, known by its nickname “the mole,” was meant to burrow 16 feet (5 meters) underground to learn how heat rises from Mars’ core. Despite the team’s best efforts, the instrument couldn’t get a grip on the soil and dig. After trying for two years, the team gave up.

“That was a bust,” Banerdt said.

A second unexpected outcome from the mission actually turned out to be a pleasant surprise. InSight carried a weather station to spot things getting in the way of measuring seismic activity — like the incessant wind on Mars. So, using a bunch of sensors collectively called the Auxiliary Payload Sensor Suite (APSS), InSight sent home daily weather reports of its Martian home in Elysium Planitia. The data covered temperatures, pressures and winds, all of which came in handy to confirm that the quakes InSight senses are really coming from the surface below.

Thanks to these sensors, “we have an unprecedentedly complete meteorological dataset for this location on Mars,” Banerdt said. “Put these things together, and I think we can mine this for science for years to come.”

InSight last phoned home on Dec. 15, 2022.

“InSight has more than lived up to its name,” Laurie Leshin, director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement soon after the mission ended. “Yes, it’s sad to say goodbye, but InSight’s legacy will live on, informing and inspiring.”

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg (opens in new tab). Follow us @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab), or on Facebook (opens in new tab) and Instagram (opens in new tab).