NASA’s dramatic Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) was a rousing success, scientists say.

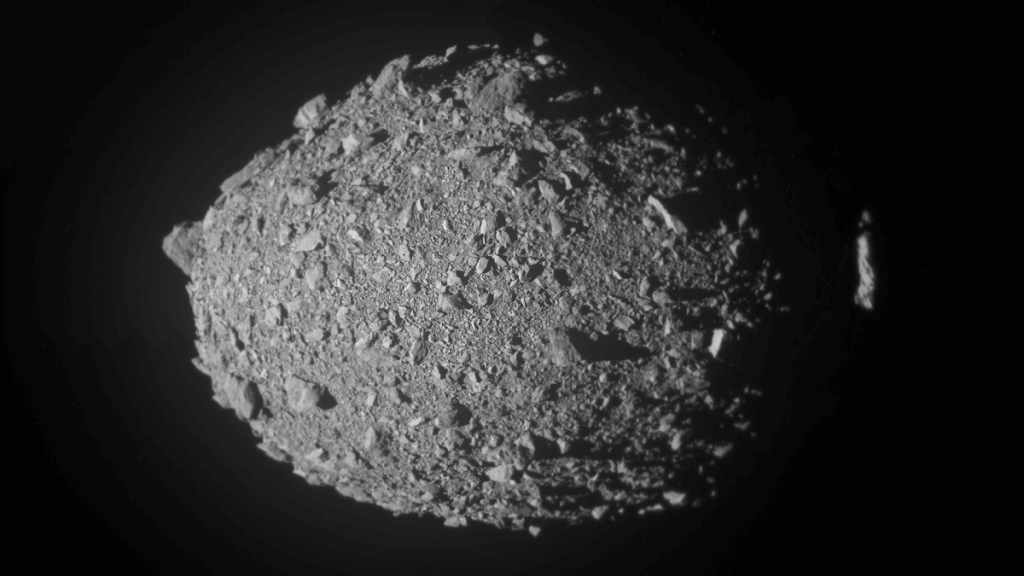

Before the DART spacecraft intentionally crashed onto Dimorphos on Sept. 26, 2022, scientists knew very little about the asteroid’s size, shape or composition. Six months later, they now have the clearest view yet of its entire body, which is 580 feet (177 meters) wide.

“I feel like it looks like a happy fish swimming to the left with its nose kind of pointed up,” Carolyn Ernst, a planetary scientist at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), said of a new high-resolution mosaic of Dimorphos, which was released on Monday (March 13) at the 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) being held in Texas and virtually.

Related: Behold the 1st images of DART’s wild asteroid crash!

The mosaic was put together using the final 10 images sent home by the Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical Navigation (DRACO), the camera onboard DART that snapped a picture of Dimorphos every second during the final four hours before DART’s impact.

“I knew the final images were going to be spectacular, and somehow they still managed to exceed my expectations,” said Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at APL. Chabot credited the mission’s success to the collaboration of a huge team, which included scientists from 100 institutes spanning 28 countries worldwide.

DART’s impact reduced the time it takes Dimorphos to orbit its larger asteroid companion, Didymos, by 33 minutes, to 11 hours and 23 minutes. To arrive at that number, scientists studied the binary Didymos system using telescopes located on all seven continents.

Over 259,000 images snapped by DRACO are now available online as part of NASA’s Planetary Data System (opens in new tab). These images show some of the 2.2 million pounds (1 million kilograms) of ejecta blasted off Dimorphos by the impact and reveal the asteroid’s surface to be covered with boulders of various sizes, helping researchers confirm the asteroid to be a rubble pile.

Using this data, scientists reconstructed DART’s final moments, including the collision itself. The probe’s targeted impact site was 25 inches wide (66 centimeters), according to Ernst. That’s smaller than DART’s cross section, so the star tracker jetting out from the bottom of the probe was likely the first piece to take the hit. Microseconds later, DART’s solar panels hit one of Dimorphos’ boulders, but there would have been no time for one part of the spacecraft to communicate to the others about the shock, Ernst said.

Scientists also announced on Monday that the names of five features on Dimorphos’ surface have been accepted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), the authority that assigns names to celestial objects.

Related: How humanity could deflect a giant killer asteroid

Some of the new research presented included DART’s final moments and Hubble Space Telescope observations of the ejecta and tail formations. These findings, which were published on March 1, highlighted the mission as the first to watch not one but two tails grow from Dimorphos. (Previously, astronomers spotted asteroids sporting tails, but they’d never seen one form.) The Hubble Space Telescope will continue observations until Didymos gets too close to the sun to be safely observed, which will happen in early July.

Scientists also said that DART created a crater 130 feet (40 m) to 196 feet (60 m) wide when it plunged between two boulders — Atabaque and Bodhran — on Dimorphos.

The entire drama was witnessed first-hand by LICIACube (short for “Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging of Asteroids”), a 31-pound (14 kilograms), smaller-than-a-shoebox satellite that hitched a ride on DART and moved away to a safe distance two weeks before impact. The satellite recorded everything it saw, including the bright flash just after DART’s crash into Dimorphos.

“From a scientific perspective, it is really a treasure trove,” said Maurizio Pajola, a planetary scientist at the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics and part of the LICIACube Science Team.

For DART’s “outstanding contribution” to the space field, the mission team was awarded (opens in new tab) the National Space Club and Foundation’s 2023 Nelson P. Jackson Aerospace Award earlier in March.

The knowledge gained so far from DART’s success is critical, but that alone is not enough to understand the mission’s impact in the broader context of planetary defense, scientists said. Applying a similar “kinetic impactor” technique to a different asteroid hazard will require a lot more research, and ongoing studies about how the resulting ejecta will evolve and behave will play an important role, they said.

Using all the data sent home by DART and more that is being collected by ground-based telescopes, scientists hope to better understand what to expect when the European Space Agency’s Hera spacecraft reaches the Didymos-Dimorphos system in 2026.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).