Scientists are turning to chemical modeling to determine whether icy moons in our solar system have what it takes to host life — microbial life, that is.

In general, chemistry models are crucial for understanding the conditions that could support life as we know it on other planets. This is achieved through modeling various factors, including climate, interstellar environments, biosignatures that are like life’s fingerprints, and the overall chemical processes that might occur in these places. But what exactly are we looking for when it comes to “habitability?” A blue paradise — or, the bare minimum?

Charity Phillips-Lander, a senior research scientist at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) who is currently studying organics in icy world laboratory analogs, has begun exploring whether this tool can help characterize the role of harsh environments in supporting microbial life.

“The question of habitability is about constraining the environmental factors that make it more likely to be friendly to life versus inhospitable,” she said in a statement. “Most geochemical modeling software doesn’t account for organics [carbon-based molecules] at the conditions expected on ocean worlds, so I couldn’t model things that I was seeing in the lab during laboratory investigations of the conditions of ice-covered moons in our solar system, like Europa and Enceladus.”

Phillips-Lander and her colleague Florent Bocher developed their own modeling software, using it to simulate the formation of organic-doped ice pores — ice structures that incorporate or interact with organic compounds via microscopic pores — and explore how these structures might behave under extreme environments. The formation of these ice pores is a phenomenon that can also occur on Earth, particularly in polar regions or in glacial ice. This process happens when ice undergoes changes such as freezing, thawing or sublimation, leading to the creation of porous structures that may trap organic molecules.

In laboratory settings, scientists intentionally create “organics-doped ice” to replicate these conditions and study how such structures might form or behave on other worlds. This includes exploring how factors like varying temperatures, pressures and cosmic radiation could produce similar porous formations — conditions that Phillips-Lander has been investigating in her own lab work.

By combining these laboratory observations with accurate computational models, researchers can gain valuable insights into how ice behaves in environments beyond Earth, with a particular focus on its potential to support life or chemical reactions under extreme conditions.

“With improvements, this tool will be able to provide a great deal of valuable information about ocean worlds,” Bocher said. “It’s one thing to know what chemical composition to expect, but it’s much more helpful to know what compounds are present, and what chemical phases they’re in.”

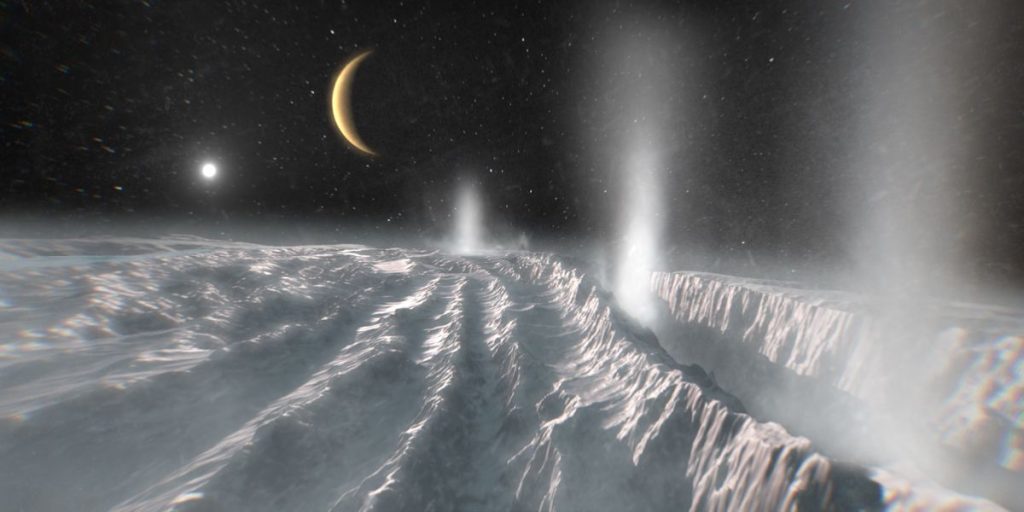

The researchers are currently focused on enhancing and refining their model to replicate the precise conditions found on distant worlds, such as Enceladus — the ice-covered moon orbiting Saturn.

Enceladus is particularly intriguing because it is believed to have a subsurface ocean beneath its icy crust, a potential environment that could support microbial life. By improving their models, the team can better simulate the unique conditions of such moons, and determine how organic compounds might behave under such conditions.

“This new project will help us collect that missing data, add it to the modeling software, and then construct those models to provide greater context for laboratory investigations into these icy ocean worlds, and hopefully also what we would see during a future mission,” Phillips-Lander said.