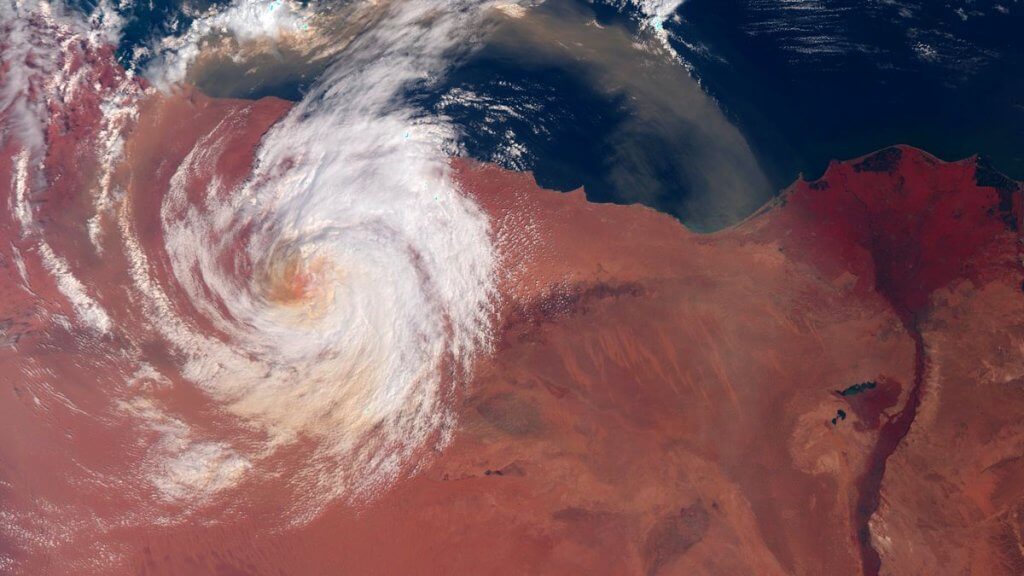

Satellites watched as a rare Mediterranean hurricane, or “medicane,” named Daniel swirled above the Sahara Desert, bringing catastrophic flooding to Libya.

The storm originally formed above Greece on Sept. 4 and dumped 18 months’ worth of rain in just 24 hours in parts of the country, resulting in catastrophic flooding. During its subsequent crossing of the Mediterranean Sea, Daniel gained strength from waters warmed by months of record-breaking heat, growing into a rare phenomenon called a medicane. Medicanes near the intensity of Atlantic hurricanes and sometimes even feature a distinct eye at their center, signs of which can be distinguished in the satellite photos of Daniel.

“Medicanes such as Storm Daniel are relatively rare, and tend to occur more frequently in the western portion of the Mediterranean Sea than the arid Libyan coastline,” Liz Stephens, a professor in climate risks and resilience at Reading University in the U.K., said in a statement. “It is more difficult to understand the potential for catastrophic extreme events in an arid climate, where even moderate rainfall events are few and far between.”

Related: New and improved satellites will help track storms this hurricane season

For Libya, the unexpected visit of such a potent storm proved devastating. According to Libya’s National Meteorological Centre, Daniel reached peak intensity on Sunday (Sept. 10), packing sustained winds of 44 to 50 mph (70 to 80 kph) and setting the country’s new daily rainfall record of 16.3 inches (414.1 millimeters). According to reports, two dams near the city of Derna failed to contain the torrents of rain water and collapsed, causing a catastrophic deluge. Thousands of people are believed to have lost their lives in the disaster, prompting Libyan authorities to declare a state of emergency.

The European Earth-observing satellite Sentinel-3 and the geostationary weather satellite Meteosat 11 both captured images showing the monster storm swirl above the characteristic orange-tinged desert surface.

Only one to three medicanes usually form in the Mediterranean region every year, Suzanne Gray, professor of meteorology at Reading University, said in the statement. Paradoxically, evidence exists that with advancing climate change, these devastating storms are likely to become less common. Those that form, however, are more likely to grow more potent than they would in a cooler climate.

“Climate change is thought to be increasing the intensity of the strongest medicanes, and we are confident that climate change is supercharging the rainfall associated with such storms,” added Stephens. “It would be interesting to evaluate whether the rainfall totals in eastern Libya would have been physically implausible without climate change. However, this is a complex question that would have to take into account any changes in storm track as well as the rainfall totals.”