Hurricane Francine, the sixth named storm of the Atlantic hurricane season, made landfall in Louisiana on Wednesday afternoon (Sept. 11) as a Category 2 storm.

The highest sustained winds at landfall in the southern Louisiana Parish of Terrebonne approached 100 miles per hour (155 kilometers per hour) with reports of higher wind gusts.

Francine also brought a life-threatening storm surge to the coastline, and heavy rain triggered flooding across parts of the Gulf Coast. Thousands of people were told to evacuate ahead of the storm and hundreds of thousands of people were without power in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama as of Thursday morning (Sept. 12)

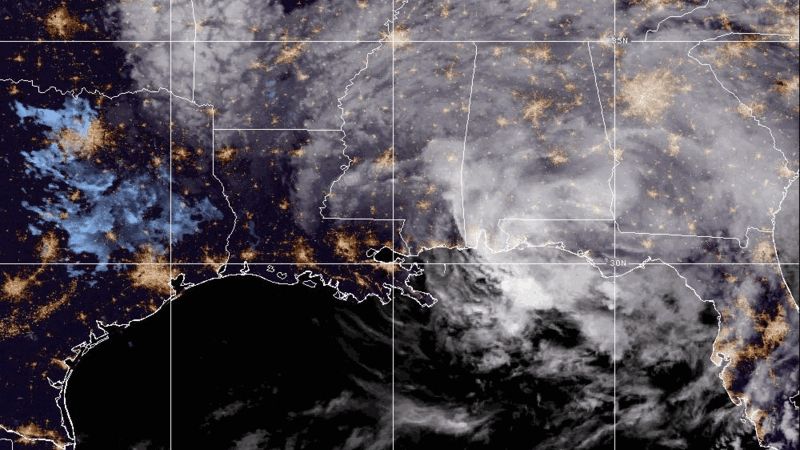

Air Mass imagery via @NOAA’s #GOESEast 🛰️ shows #Francine, now a depression, moving inland over the southeastern U.S. this morning. Heavy rainfall is spreading across Mississippi, Alabama, and the Florida panhandle. Latest advisories: https://t.co/wJGBXDcfEu pic.twitter.com/x0Eo6veFRZSeptember 12, 2024

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s GOES-East satellite has been documenting the progression of the storm since it began to develop in the central tropical Atlantic at the end of August.

Francine strengthened into a tropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico on Sept. 9 and then a day later, on the climatological peak of hurricane season (Sept. 10), became the fourth hurricane of the Atlantic Season.

Related: Satellites watch Tropical Storm Francine threaten Gulf Coast (video)

Sep 11: Hurricane Francine rainbands continue to spread inland into southern Louisiana. Francine is moving toward the NE and is anticipated to make landfall in Louisiana within the warning area later this afternoon or this evening. Very dangerous wave heights to 33 ft ongoing. pic.twitter.com/m9EOTRiVt0September 11, 2024

Forecasters continue to use two of the instruments on the satellite to get the best picture of the storm, the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) and Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM). There are three different types of channels — visible, near-infrared, and infrared — that make up 16 total variations on the ABI.

By utilizing the different wavelengths, forecasters can keep a watchful eye on hurricanes from space around the clock and obtain data to learn more about the storms’ structure and intensity in near-real time. The GLM can also provide clues to the continuous changes in a hurricane’s intensity and composition based on the amount of lightning strikes at a given moment or over a period of time.

Sept 10 – @NOAA WP-3D Orion #NOAA43 “Miss Piggy” is flying into TS #Francine to assess if it’s intensifying into a hurricane. Data collected will refine intensity forecasts and support hurricane research. Visit https://t.co/3phpgKMZaS for the latest updates. #FlyNOAA pic.twitter.com/MVQfn5LX31September 10, 2024

NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft also relies on information provided by satellites for their missions to collect data on a storm. The information obtained on flights both into and around storms help forecasters have a better understanding of how intense storms are and provide other important information on their conditions and trajectories.

Francine will continue to weaken now as it continues inland but will still pose threats of more flash and urban flooding Thursday (Sept. 12) across the Gulf Coast from Louisiana to the Florida Panhandle and then from the Lower Tennessee and Mississippi Valleys through Friday morning (Sept. 13). There will also be a threat of tornadoes as well embedded within the bands of the storm.

You can continue to find updates and details on any alerts for Francine on NOAA’s National Hurricane Center website and through trusted local media outlets.