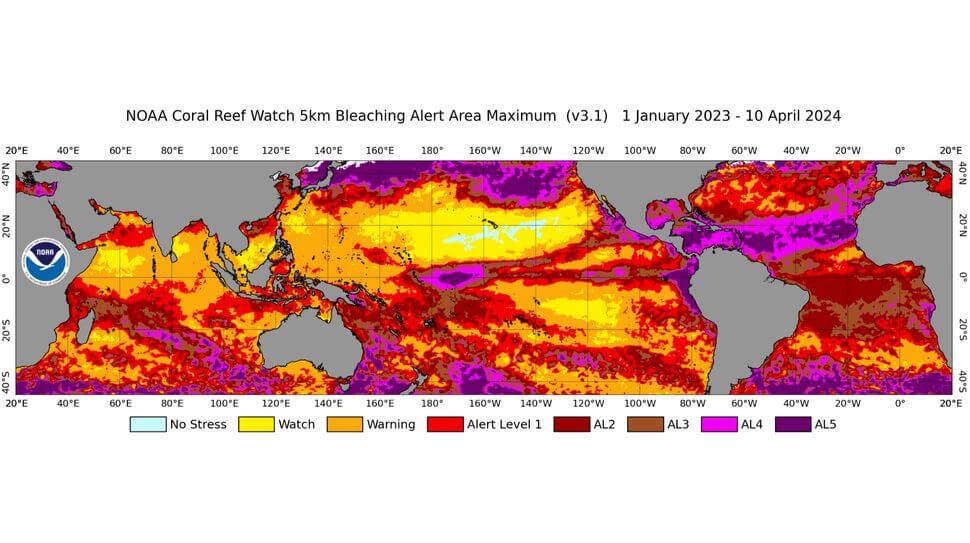

Multiple major coral reefs around the world are getting paler due to warming sea temperatures in the fourth-ever global bleaching event, and satellites are keeping tabs on the carnage.

The grim event, the second in a decade, is affecting over half the world’s coral area across the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans. The toll includes what could be the worst bleaching ever experienced by Australia’s famous Great Barrier Reef, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the International Coral Reef Initiative, which confirmed the bleaching event on Monday (April 11).

Coral bleaching occurs when corals become stressed and leach out symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae live inside corals and are crucial to their survival; without zooxanthellae, corals not only lose their color but are at risk of starvation and disease. Corals, which are actually animals and support the livelihoods of millions of people, begin to die if warmer temperatures persist in the waters in which they are rooted.

Related: Satellites help scientists see how coral reefs are dealing with climate change

“As the world’s oceans continue to warm, coral bleaching is becoming more frequent and severe,” Derek Manzello said in an April 15 statement. Coral mortality “hurts the people who depend on the coral reefs for their livelihoods.”

From their vantage point in Earth orbit, satellites regularly collect data about ocean temperatures, water quality and changes to coral colors, which help scientists identify at-risk reefs.

Data they beam to Earth helped create the world’s first tool to monitor coral bleaching in real time, which was released by the Allen Coral Atlas in 2021. The tool creates mosaics of coral reefs worldwide based on images of Earth’s surface snapped by Europe’s two Sentinel-2 satellites and spacecraft owned by the San Francisco-based company Planet. Planet operates many satellites, including a flock of 150 shoebox-sized “Dove” cubesats.

On a bi-weekly basis, the Allen Coral Atlas processes Sentinel-2 data for regions that NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch daily monitoring program independently flags as potential bleaching events. Then, based on a baseline data of cool water temperatures, the tool detects and tracks whitening of coral reefs that indicates bleaching is underway.

In the past, a short-term mission by NASA used an instrument-fitted airplane to collect data on the decline of the Great Barrier Reef for three years, from 2016 to 2019. The CORAL mission, short for Coral Reef Airborne Laboratory, also flew over reefs in Hawaii, Palau and the Mariana Islands and cataloged the prism of light reflected from the ocean, which was then used to identify the reef’s composition.

Scientists worry that coral bleaching events are becoming more severe and frequent due to increased marine heatwaves driven by climate change. Last year was particularly stressful for corals, as global sea temperatures spiked to record-high levels for several months. In February, for instance, mass coral deaths were reported in the Florida Keys after a bleaching event caused by an unprecedented, prolonged heat wave killed substantial corals and scuttled scientists’ efforts to restore the region’s declining reefs. Coral deaths were also documented in reefs near Cuba and the Bahamas.

In February, a high-resolution map of the spread of coral reefs from Sentinel-2 and Planet satellites revealed that corals span more of our planet’s oceans than previously thought. Those maps were made publicly accessible and are being used for coral conservation efforts worldwide, scientists say.

“This data will allow scientists, conservationists and policymakers to better understand and manage reef systems,” Mitchell Lyons of the University of Queensland in Australia, who is part of the Allen Coral Atlas project, said in a statement. “It’s more than just a map — it’s a tool for positive change for reefs and coastal and marine environments at large.”