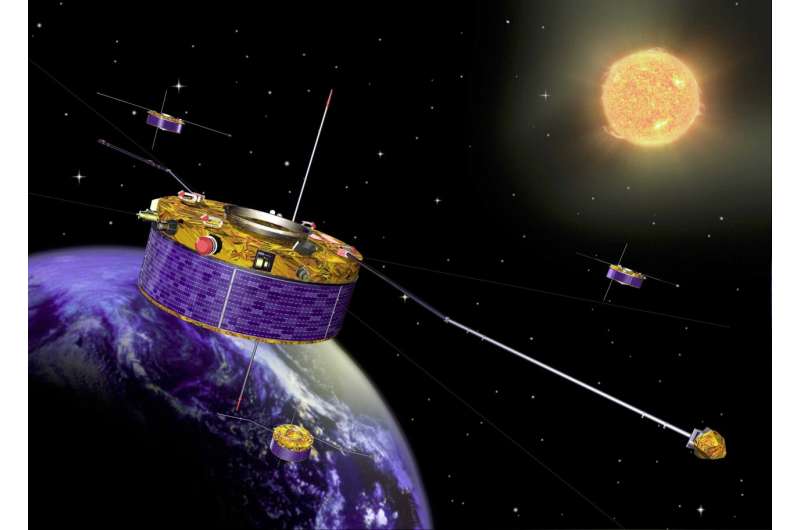

Launched in 2000, Cluster is a unique constellation of four identical spacecraft investigating the interaction between the sun and Earth’s magnetosphere—our shield against the charged gas, energetic particles and magnetic field coming from our star.

Despite a planned lifetime of two years, the Cluster mission has now spent almost 24 years in orbit.

Over the past two and a half decades, Cluster’s observations have led to the publication of more than 3,200 scientific papers and counting.

They have provided scientists with essential insights into the sun’s impact on the Earth environment and the processes taking place within Earth’s magnetosphere, and improved our understanding of potentially hazardous space weather.

The sun-Earth connection remains an important topic of study, particularly during the current period of high solar activity.

The Cluster satellites will continue to make observations up until September 2024. During their last few months of scientific activity, they will pass through the region in which charged particles are accelerated before producing Earth’s auroras. Researchers will capitalize on the rare chance to study this region using instruments on multiple satellites at the same time.

The decades of data stored in the Cluster science archive will continue to enable new science long after the end of the mission. With this treasure trove of data, researchers can revisit and reanalyze past events, conduct new statistical analyses and implement new machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques.

Salsa’s final steps

Of the four Cluster satellites (named Rumba, Salsa, Samba and Tango), Salsa will be the first to take the plunge back into Earth’s atmosphere.

Operators at ESA’s ESOC mission control center carried out four maneuvers this January to lower Salsa’s orbit and prepare the satellite for a safe atmospheric reentry in September over a sparsely populated region of the South Pacific Ocean.

“The Cluster satellites have highly eccentric orbits that are strongly impacted by the gravitational pull of the sun and the moon,” says Bruno Sousa, Head of Inner Solar System Mission Operations at ESOC. “Sometimes, they drop steeply, by more than 30 km in a single orbit. Other times, they don’t drop at all.”

“This month, we tweaked Salsa’s orbit to make sure it experiences its final steep drop from an altitude of roughly 110 km to 80 km in September. This gives us the greatest possible control over where the spacecraft will be captured by the atmosphere and begin to burn up.”

The timing of the maneuvers was important. Salsa’s “eclipse season” begins in February. The satellite will spend most of the next few months switched off while located in Earth’s shadow and unable to rely on its solar arrays to generate power.

“Salsa’s solar arrays have also been degrading fast since it crossed the Van Allen radiation belts. Maximum available power is decreasing fast and could soon reach a point at which we would be unable to perform the deorbiting maneuvers,” says Beatriz Abascal Palacios, Cluster Operations Engineer.

Unique chance to improve space sustainability

The remaining three spacecraft in the Cluster quartet will continue to carry out scientific observations, with a particular focus on auroral physics, until September. Salsa may join in for some final observations too, if it is still able to generate enough power after the eclipse season.

Like many of our satellites, the Cluster spacecraft were designed and launched before ESA’s current guidelines for limiting the creation of space debris came into effect.

Nevertheless, ESA is taking action to minimize the environmental impact of its older missions. Last summer, we guided ESA’s wind mission, Aeolus, back to Earth over sparsely populated regions in a first-of-its-kind assisted reentry. Thanks to this month’s activities, Salsa’s reentry in September will take place over a region of similarly sparse population, air, and maritime traffic.

Following Salsa’s reentry, the remaining Cluster satellites will enter “caretaker” mode—controlled, but carrying out no new science—until they, too, reenter Earth’s atmosphere in a similar fashion. Rumba will reenter in 2025; Tango and Samba will reenter in 2026.

“This is the first time that anyone has targeted the reentry of a satellite with an eccentric orbit like Salsa in this way,” says Stijn Lemmens from ESA’s Space Debris Office. “And the end of the Cluster mission gives us the unique chance to reenter four identical spacecraft at different times.”

“The experience we gain from safely reentering the same satellite at four different angles and speeds, and under four different sets of atmospheric conditions, will greatly improve our understanding of reentries and help us define the standard for the safe disposal of satellites in similar orbits.”

Provided by

European Space Agency

Salsa’s last dance targets reentry over South Pacific (2024, January 26)

retrieved 27 January 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-01-salsa-reentry-south-pacific.html

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.