A nonprofit organization has called on the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to pause satellite megaconstellation launches until it can assess the environmental impact of placing thousands of spacecraft in orbit.

Over the last few years, scientists have begun calling attention to the risks large numbers of satellites pose to our atmosphere, climate, orbital safety and astronomical research. A study by University of California researchers, published in June, concluded that chemicals produced by the incineration of large numbers of satellites during atmospheric reentry have a potential to “significantly” damage Earth’s recovering ozone layer. Another study, presented by a team with the U.S. National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA) in January, found that the expected increase in concentrations of those chemicals in Earth’s upper atmosphere will produce “statistically significant stratospheric temperature anomalies.”

In the past, only a handful of governmental institutions worldwide operated satellites. Launches were relatively few and far between, and only a few hundred spacecraft circled the planet. But that has changed. SpaceX alone has already deployed more than 6,000 of its Starlink broadband satellites and has plans to build a constellation of 40,000 such spacecraft. Other megaconstellations are in the works as well, including Amazon’s Kuiper and the Chinese ventures Qianfan (also known as G60) and Guowang.

Despite this step change, regulators in the U.S. pay little attention to the potential environmental impacts of space technology, critics say. In fact, satellite megaconstellations are excluded from environmental reviews by the FCC, which awards satellite licenses in the U.S.

Related: SpaceX’s Starlink satellites: Facts, tracking and impact on astronomy

Stop it now!

A federation of U.S. and Canadian nonprofit organizations has now launched a petition urging the FCC to stop this practice before too much damage is done.

“We recommend the FCC to pause all future launches of satellite internet megaconstellations until the environmental review has been established,” Lucas Gutterman, director of the Designed to Last Campaign at the nonprofit Public Interest Research Groups (PIRG), told Space.com. “We should pause and not rush into a new ecosystem where the effects are not totally clear, especially if it could cause a mess that requires potentially decades to clean up after ourselves.”

Satellites are mostly made of aluminum, which turns into aluminum oxide when burned. This chemical is a cause of concern for scientists, as it is known to damage ozone and can affect how much heat Earth radiates into space and how much it retains in the atmosphere. Researchers have compared the unchecked release of those chemicals into the previously pristine upper atmosphere to an uncontrolled geo-engineering experiment. As these particles accumulate at altitudes of tens of miles, their concentration would take decades to decrease once effects set in.

“We are rewarding companies for being the first to launch rather than having a comprehensive plan that balances the benefits to the public interest versus the environmental harms,” said Gutterman. “Personally, I think it offends common sense that launching up to 40,000 satellites doesn’t even warrant an environmental review. But the FCC, which grants licenses to satellite operators in the U.S., has categorically exempted all satellites from environmental review.”

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) criticized the exemption in 2022, saying that the FCC had “not sufficiently documented its decision to apply its categorical exclusion when licensing large constellations of satellites.”

Related: Kessler Syndrome and the space debris problem

40-year-old exemption

U.S. government authorities are bound by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to evaluate the environmental effects of their decisions and consult the public. Categorical exclusions, such as that granted to satellite operators, exempt some projects from this requirement.

Ian Christensen, senior director for Private Sector Programs at the nonprofit Secure World Foundation, told Space.com that the exemption from environmental reviews was put in place in 1986 and has not been revisited since.

“The exemption primarily was based on impacts to things on the ground, not even really considering atmospheric impacts at the time,” Christensen said. “It’s definitely fair to say that we are looking at a much different type of activity now. Things have changed since 1986, and it is perfectly reasonable to ask the FCC to review this exemption.”

In response to a request by Space.com, the FCC didn’t comment on the justification for the exemption’s continuation but referred to its 2022 letter to the U.S. Senate, in which the agency states that it expects to “conduct a review of its NEPA rules” after the Council of Environmental Quality, which coordinates the U.S. government’s environmental protection, revises NEPA implementation procedures, a process that is currently in progress.

The FCC is not the only regulator that should respond to the new situation, according to Christensen.

“We’ve just seen a launch of the first batch of satellites of the Chinese G60 constellation,” he said. “There are plans in Europe and in other countries as well, so we need a holistic solution.”

Not like meteorites

Earth’s atmosphere is constantly bombarded by meteorites, but these natural space rocks have a different chemical composition and contain no aluminum. And the number of satellites in Earth orbit is skyrocketing. There are currently about 10,000 active spacecraft zooming around our planet, according to the European Space Agency — roughly four times as many as there were just six years ago. Companies like SpaceX launch small satellites, which they intend to replace frequently with new, more capable technology. As a result, an unprecedented number of discarded satellites will be burning up in Earth’s atmosphere within a decade. PIRG estimates that, within 10 years, some 29 tons of metal will be undergoing the fiery atmospheric demise every day, an equivalent to a “Jeep Cherokee falling from space every hour.”

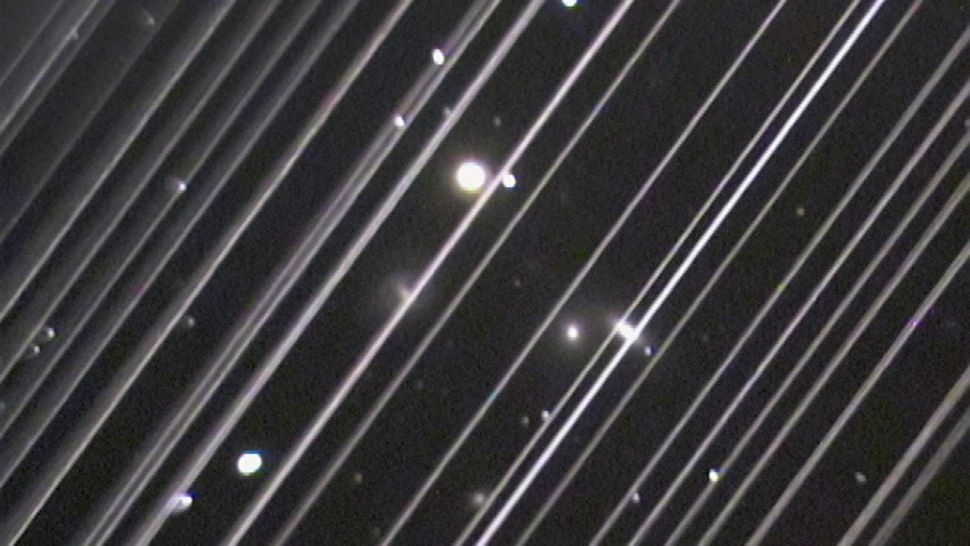

Researchers are also concerned about the rising numbers of rocket launches as rocket exhaust, too, contains chemicals that are likely to mess up atmospheric chemistry. And space safety experts further warn about the growing risk of collisions due to the skyrocketing orbital traffic and the increasing amount of space debris hurtling around our planet. They fear that a few unfortunate smashups could render the space around Earth unsafe or even unusable. In addition to that, astronomers have been voicing their concerns about the impacts of LEO satellite megaconstellations on their ability to observe and study the cosmos. PIRG estimates that, if all existing satellite megaconstellation plans come to fruition, satellites visible in the night sky will outnumber stars 15 to 1.

The petition will remain open for signature for the next “couple of weeks,” said Gutterman. PIRG also launched a report summarizing the scale of the problem.

Internet-beaming satellite megaconstellations are pitched as a solution to the lack of internet accessibility in remote parts of the world. Gutterman, however, questions whether such vast numbers of spacecraft are needed to plug those connectivity gaps.

“Research suggests that we could achieve those global connectivity goals with just around 300 satellites and a mix of higher-capacity satellites at different orbits,” Gutterman concluded.