Twelve years after OSIRIS-REx was chosen to be NASA’s ambitious asteroid-sampling endeavor, the mission’s probe is set to deliver more than 2 ounces (60 grams) of material from a space rock named Bennu on Sunday morning.

Scientists are very excited to study this sample because Bennu is believed to be a remnant of the early solar system and its matter could therefore shed light on how our solar system’s planets formed. Potentially, these samples may even reveal the building blocks that led to life on Earth. However, there is no reason to suggest that there is anything biological on Bennu itself.

Specifically, Bennu is a small, dark object with a very dry and very hot surface. This means there is no evidence for flowing water on the asteroid, so it is not the type of object we expect to be conducive to sustaining life, scientists say.

“It is an ancient dead rock that will be super exciting to study for lots of reasons not related to biology,” Jason Dworkin, the project scientist for the OSIRIS-REx mission, told Space.com. He added that the sample return is considered a Category 5 “Unrestricted Earth Return,” which means the incoming samples have no restrictions, including those pertaining to biology.

Related: How NASA’s OSIRIS-REx will bring asteroid samples to Earth in 5 not-so-easy steps

Read more: OSIRIS-REx’s asteroid sample will come down to Earth on Sept. 24. Here’s how to watch it live.

Every September, Bennu passes close enough to Earth’s orbit that it causes meteor showers in Earth’s southern hemisphere. Scientists think these events rain down centimeter to millimeter-size bits. In 2019, they searched for those pieces in Australia, Chile, New Zealand, South Africa and Namibia. They spotted a few candidates but could not find conclusive evidence that they were originating from Bennu, according to the 2019 study.

“There isn’t biology on Bennu but even if there was, it is already on Earth,” Dworkin told Space.com. “So there is no need for any alarm or concern.”

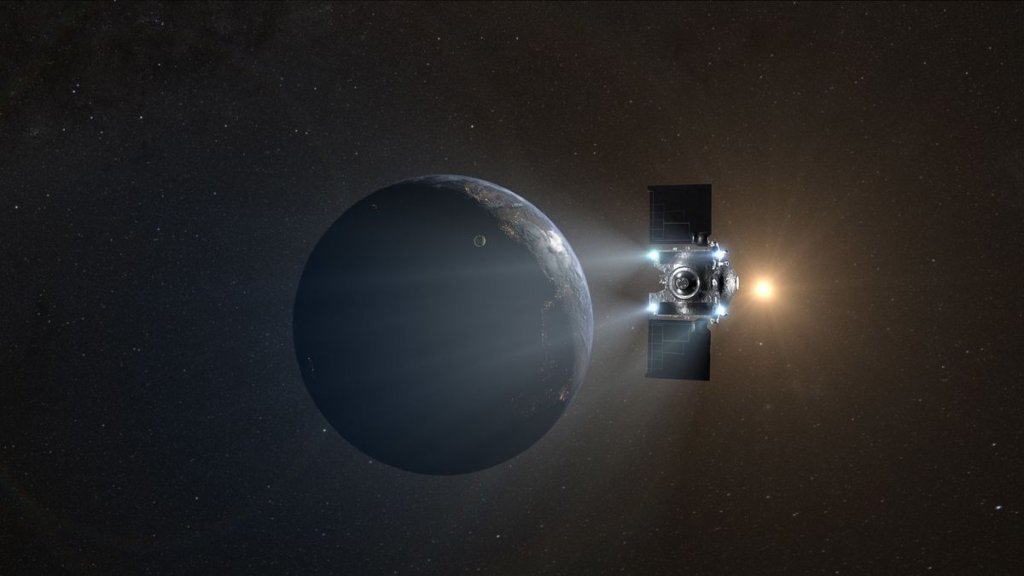

Ever since NASA‘s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft collected the sample from Bennu in 2020, the material has been protected such that it doesn’t get too hot while re-entering Earth’s atmosphere, where it will reach speeds of up to 27,000 mph (43,452 kph) before slowing prior to touch down.

A filter in the canister where the sample is kept lets air in but keeps out moisture, dust and organic material, Dworkin said, which ultimately preserves the sample until it can be properly analyzed.

After the sample touches down this Sunday morning in the Utah Test and Training Range in the state’s West Desert, it will be taken into a nearby clean room for an ultra-pure nitrogen purge to prevent external matter from getting inside the canister. Early next week, the sample will be sent to a newly built clean room at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. There, it will be stored in a glove box and once again undergo a nitrogen purge, Dworkin said, such that it can be opened up and imaged without exposure to Earth’s atmosphere.

A team of scientists will begin studying the sample shortly after its arrival in Houston, and those initial findings are expected to be released within the next few weeks.

“We won’t find life itself, but we’re definitely looking at the building blocks that could have eventually evolved into life,” Michelle Thompson, who is an associate professor in Purdue University’s College of Science and one of the six lead investigators who will get a first peek at the asteroid sample, said in a statement published Monday (Sept. 18).

Over the course of one year, small amounts of the sample will be shipped to about 200 scientists at various institutions around the world for further analysis with various instruments.

Some of the moon samples brought home during the Apollo missions were put in a deep freeze for over 50 years. Just last year, scientists at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland began studying those frozen samples using new techniques that were not available back in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Similarly, about 70% of the returned sample from Bennu will be stored in sealed containers “so that scientists from as soon as 6 months from now to decades from now can look at the samples themselves and ask their own questions with their own instruments [about] things that we may not have thought of today with techniques we can’t analyze today,” Dworkin said.

For now though, the goal and challenge for scientists throughout is to prevent earthly contamination to the asteroid’s sample, “so that we can look at what Bennu tells us instead of what Earth tells us,” Dworkin said.